More than Words Alone Can Say: Writing with Images in the Digital Age

Last week, on the day before Thanksgiving vacation, several of my fifth-graders voluntarily stayed after school with me to work on a project for which they would receive no grade: producing calendars based on poems and illustrations they had created for a class project.

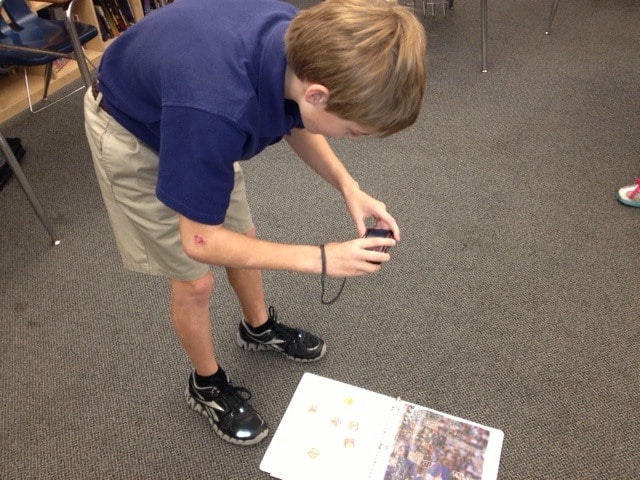

We were at step two, taking digital images of their illustrations. As I put real cameras in their hands to shoot pictures of their work we will upload to online publisher Lulu, they were giddy with excitement. All eyes were on me as I told them what to do. “Put the camera strap around your neck or your wrist; keep your elbows at your sides; hold your breath as you shoot,” I instructed.

Contrary to our usual classroom interactions, in this case, I did not have to tell them two or three times – and they followed my instructions to the letter. I was reminded once again of how meaningful it is for students to express themselves in words and images.

Revisiting Visual Literacy

Despite more than a century of being bombarded with advertising and other media, educators all too often underestimate the importance of how we communicate using images.

The International Visual Literacy Association credits John Debes with coining the term “visual literacy” in 1969. According to the IVLA, Debes emphasizes the competencies of the visually literate person as those which enable him or her “to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, symbols, natural or man-made” present in his or her environment.

By 2003, Dr. Anne Bamford of the University of Technology, Sydney, defined visual literacy at its simplest as “interpreting images of the present and past and producing images that effectively communicate the message to an audience” (“Visual Literacy White Paper”).

Since then, the National Council of Teachers of English has exhorted its constituency to bring its teaching up-to-date with two important position statements on “Multimodal Literacies and Technology” and “NCTE Beliefs about the Teaching of Writing.”

The former recognizes that our current students have become sophisticated readers and producers of multimodal works, largely on their own, “though they can be helped to understand how these works make meaning, how they are based on conventions, and how they are created for and respond to specific communities or audiences.”

The latter document recognizes the visual impact of printed text itself, then goes on to assert, “As basic tools for communicating expand to include modes beyond print alone, ‘writing’ comes to mean more than scratching words with pen and paper. Writers need to be able to think about the physical design of text, about the appropriateness and thematic content of visual images, about the integration of sound with a reading experience, and about the medium that is most appropriate for a particular message, purpose, and audience.”

I’ve explored the relationships of words and images ever since my early teaching days when I would ask college-age students to analyze a work of art in a museum to improve their critical thinking skills or to wrestle with an interpretation of an advertisement in order to broaden their awareness of cultural influences on their ideas.

Where I once banked on their lack of familiarity with decoding visual content as a way to goose them into thinking more deeply (rather than formulaically as they had been taught to do with written texts), I now find that my students not only combine images and text as a matter of course, but that their eyes glaze over when they encounter any sort of text-heavy document. It’s about time that we reckoned with their new skill sets and propensities as we redesign our teaching for a new age.

Words and Images Side-by-Side

Words by themselves make powerful images that have infiltrated our daily lives. If the TED talk has given us a new model for public speaking, it has done so partly by exploiting the power of projecting a single word or phrase on a screen. Pechakucha, which employs “20 slides x 20 seconds,” takes the TED Talk concept and puts it on steroids. Likewise, the word cloud (called a “tag cloud” on Wikipedia) allows us to visually weight words by reproducing words in a larger font depending on their frequency – and thus assess their impact with amazing immediacy far superior to the old-school concordance.

Anyone who has posted a picture on Facebook and consequently generated a lively conversation has tapped into the power of communicating simultaneously with text and images. Mobile readers allow us to access enhanced texts that provide visualized contexts for deeper understanding. Students can also understand texts better by annotating them with images, whether by using a simple slideshow, by working in a Google document (as I have written about in a blog post for Voices from the Learning Revolution), or by contributing to a community of annotators such as Book Drum.

We also ignore the potent impact of infographics at our own peril. This now ubiquitous medium for conveying information combines visual design, information, and text in a way that speaks volumes. Katherine Schulten, of the New York Times “Learning Network,” provides a great overview for “Teaching with Infographics.” Kathy Schrock shares numerous resources for “Infographics as Creative Assessment.” Keeping us on our toes, mathematics teacher and blogger Dan Meyer has spurred a movement that encourages critical reading of “information design,” which can as easily misinform as it does inform.

Dipping my toe into the waters of infographics by using Easel.ly, I recently created a visual depiction of my own “independent reading” for the past few months. When I present this task as an assignment for my fifth-graders next week, I predict the same kind of enthusiasm I witnessed when I put cameras in their hands. Trying out this new medium also led to a professional epiphany when I asked myself, “Why am I not using infographics, rather than plain, boring Times New Roman on a white background, to convey the details of my course assignments?”

Pictures and Text Working Together

Blogging is a natural medium for blending images and texts, as I pointed out in a previous post for Getting Smart. “10 Reasons Why I Want My Students to Blog.” Sara Carter, commenting on that post, rightly pointed out that I should mention photo-blogging, where photos dominate or entirely tell the blogger’s story. In some cases, an elegantly worded caption (a skill I think photo-bloggers might develop in many cases) provides important textual information a photo cannot express on its own. At the same time, I’ve found that adding images to blogs sometimes provides a tidy metaphor to illustrate a point; other times images become part of the text itself, as they did in my latest post, “Tales of a Closet Tweeter.”

The relationship – or tension — between words and text, writing and illustration, can be further explored in digital posters, such as those created using Glogster. Like the infographic, a digital poster provides an opportunity for teaching elements of design. Marry your images to your audible text with VoiceThread or Fotobabble, and you’ve moved into the realm of digital storytelling.

Images and Study Skills

Anyone who has taught vocabulary by having students create imagined visualizations understands to power of using images to help students learn, even at the most mundane level of study skills. Heck, the concept of a visual dictionary transforms language acquisition entirely. Consider the bouncy molecule-like format of Snappy Words or the blended venue of Princeton’s Shahi, which combines Flickr images with Wiktionary content. Think of the power of tools like MindMeister and bubbl.us to help us brainstorm and map out our ideas. Even traditional, mindless note-taking can be replaced with snapping a picture of the teacher’s scribbled notes with a mobile phone or iPad camera and saving the photos to Evernote (which can make the images’ text searchable). Not only does this allow the student to spend his or her time studying rather than copying, but it insures that the information the student studies is actually correct.

Our Turn

As text and image converge and blend, complement or replace one another, and become something new, our ways of reading and writing and studying have become transformed as well. If we want to help our students become effective communicators, that is, effective users and producers of image-texts, we need to understand these media from the inside out and become better users and producers ourselves.

Lisa Siese

So timely... my class (online Masters) is working on this very topic this week!

I also liked your link to Snappy Words; we do a Word a Day activity at our school (I teach grade 5) with a picure/graphic component, and some of the pictures have been getting a little scrappy lately. Maybe this will inspire them!