Internet Access in Schools: E-rate Trends and the End of Net Neutrality

We’ve recently spent quite a bit of time thinking about what the end of net neutrality may mean for education. While not much has changed in the weeks following the FCC’s vote to repeal net neutrality (internet service providers have remained understandably quiet), we nonetheless continue to worry, along with most other education stakeholders. Today, we’re reposting a recent article from The Hechinger Report that echoes our concerns.

By Tara García Mathewson.

This story was originally published by The Hechinger Report.

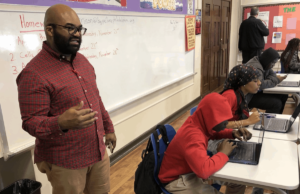

Internet access has transformed teaching and learning. In many schools, internet connectivity is a basic prerequisite for lessons in every subject, at every grade level. While this is a problem for schools that don’t have Wi-Fi or a strong enough connection to rely on, the good news is that the portion of schools that don’t is shrinking every year.

EducationSuperHighway, a nonprofit dedicated to upgrading internet access in public schools, now reports that 94 percent of school districts have a minimum level of high-speed internet. That leaves about 6.5 million students without it, and many of them attend rural schools that don’t just lack the money to buy this access but also the local infrastructure that would facilitate it.

Still, the connectivity gap, as tracked by EducationSuperHighway, has narrowed by 84 percent since 2013, thanks in part to changes in the federal E-rate program that allowed schools to use the funding to get or improve their Wi-Fi. Money to fund E-rate is collected from telecommunications companies (but, really, their customers) and made available to schools and libraries. The program provides discounts of up to 90 percent on goods and services. The money in the fund doesn’t come from taxes, and stands to benefit schools and libraries in every congressional district in the country — two reasons why the 20-year-old program has never truly been at risk of being cut.

“It’s one of probably the few things Congress can totally agree on and rally around, especially because it doesn’t come out of their budget,” said John Harrington, CEO of Funds for Learning, a consulting firm that releases annual reports about E-rate trends and helps clients from all 50 states file E-rate applications.

The firm’s 2017 E-rate Trends Report, released last week, found that the program supported $4.5 billion in services last year. Collectively, about 23,000 applicants requested $3 billion in discounts through the program, the vast majority of which were for data and internet service.

Harrington has found that the shift to online learning creates an exponentially growing challenge for school districts as they work to keep up with demand from classrooms. Fully 90 percent of respondents to a 2017 Funds for Learning survey said they expect their school’s or district’s bandwidth to increase over the next three years. This is not a challenge solved by a single purchase in a single year.

And now a new wrench has been tossed into schools’ reliance on the internet for classroom activities. The Federal Communications Commission voted last week to abandon “net neutrality” protections approved during the Obama administration. That gives internet service providers the freedom to speed up or slow down access to certain websites, making some online actions more tedious or even impossible. Some worry that reliable, fast internet service will become something only guaranteed to those who can pay extra for it.

Keith Krueger, CEO of the Consortium for School Networking, or CoSN, said the vote means schools could face a bleak reality of reduced choices, higher prices and fewer innovative tools.

“The Internet has long been a linchpin in educational innovation, cultivating unlimited ideas for using broadband networks in new, exciting ways,” Krueger said in a statement. “Today’s decision hobbles the Internet’s promise – with unexpected consequences to come.”

The idea of net neutrality has been hotly debated for at least a decade, with policy swings based on which party controlled the FCC. Net neutrality advocates have already responded to the latest ruling with the promise of a lawsuit.

In the meantime, schools likely won’t see any immediate consequences of the new policy, and most internet service providers have assured customers they don’t plan to make any changes. But as Krueger said, the potential consequences are great, and education officials shouldn’t ignore them.

For more, see:

- What the End of Net Neutrality Would Mean for Education

- Three Key Factors Perpetuating the Socioeconomic Achievement Gap

- Capitalism that Works for Everyone

Tara García Mathewson is a staff writer at The Hechinger Report. Connect with her on Twitter at @TaraGarciaM.

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.