3 Ways to Teach Everything Through Inquiry

Kimberly Mitchell

Anything that jolts me out of the discomforts and monotony of flying is welcome to me these days; an extra bag of peanuts, an empty row, a surprise upgrade to first class (never happens). But nothing could have prepared me for this recent experience.

Seated right behind passengers in the exit rows, I could overhear the flight attendant’s instructions about their responsibilities in the unlikely event of an emergency landing. Upon listening to the flight attendant, each passenger usually affirms his or her understanding and commitment with a simple head nod. But this drill didn’t take place as I usually see it happen.

Instead, the flight attendant asked everyone to not just listen but follow along with the brochure (meaning, they were asked to hold one in their own hands). Then, they were asked to turn to the person sitting next to them and verbally share the plan. Finally, they were asked to shake hands on it. Wow! In the unlikely event of an emergency landing, I’d much rather have these folks springing into action.

Brain science is on this flight attendant’s side, too. Talking reinforces the learning. The cognitive demand of understanding the procedures were placed squarely on the shoulders of the passengers, not the flight attendant. The physical connection of a simple handshake fires up all sorts of neurons and establishes trust.

This flight attendant applied the most powerful teaching strategies in a non-classroom context. And it got me thinking: If inquiry-based teaching is superior to traditional teaching, could or should it replace the way we teach everything to everyone? How would it change our communication style? Our hierarchies? Our relationships?

In inquiry teaching, the learner constructs meaning from new information (the brochure) and experiences (thinking through a scenario). This is not radical. This is actually how most people learn best. Traditional teaching, however, relies on the teacher constructing meaning and telling. Telling isn’t good teaching and yet it persists, like a stubborn habit. It is easy and efficient, but less effective.

Changing a habit requires baby steps and discipline. There are three simple steps any of us can implement right away, whether you teach physics, coach soccer or instruct passengers in how to help out in the unlikely event of an emergency landing.

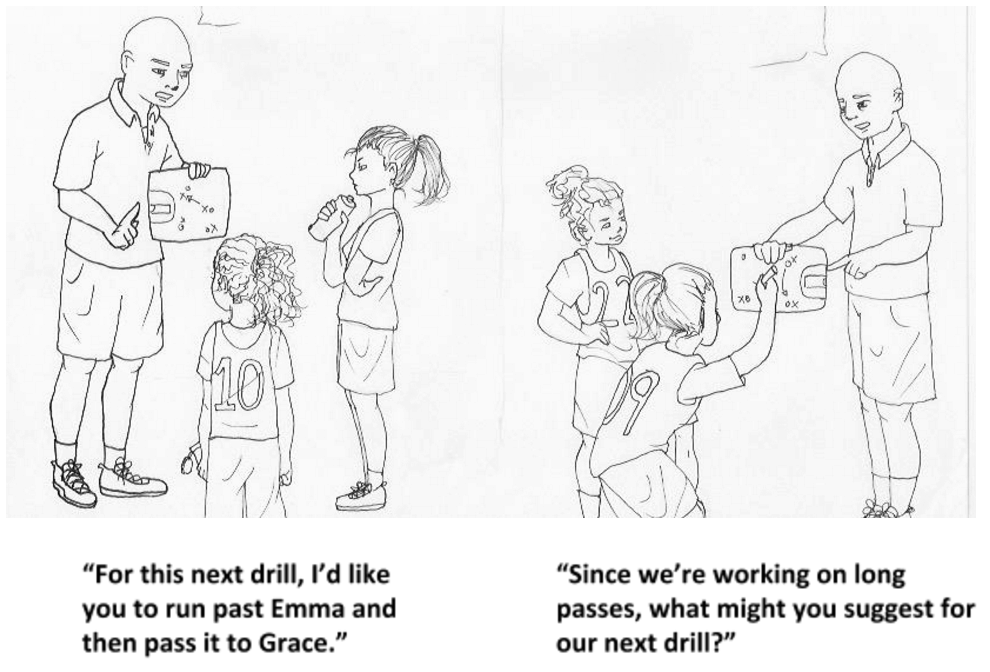

1. Ask More; Talk Less

This is the golden rule of great teaching and Socrates was the master of this practice. At their best, great lectures capture the interest and imagination of the learners (usually in the form of stories). At their worst, they induce sleep or feel agonizing. Talking continuously without pausing for a reflection activity, to ask questions, or to solicit questions, misses important opportunities for the learner to integrate and deepen the learning. Ideally, the learners are the ones doing most of the talking, especially after absorbing new information through listening, reading or experiencing something. By asking questions and periodically asking learners to turn and talk with a neighbor to answer these questions, we greatly increase the chances of the information sticking and being activated.

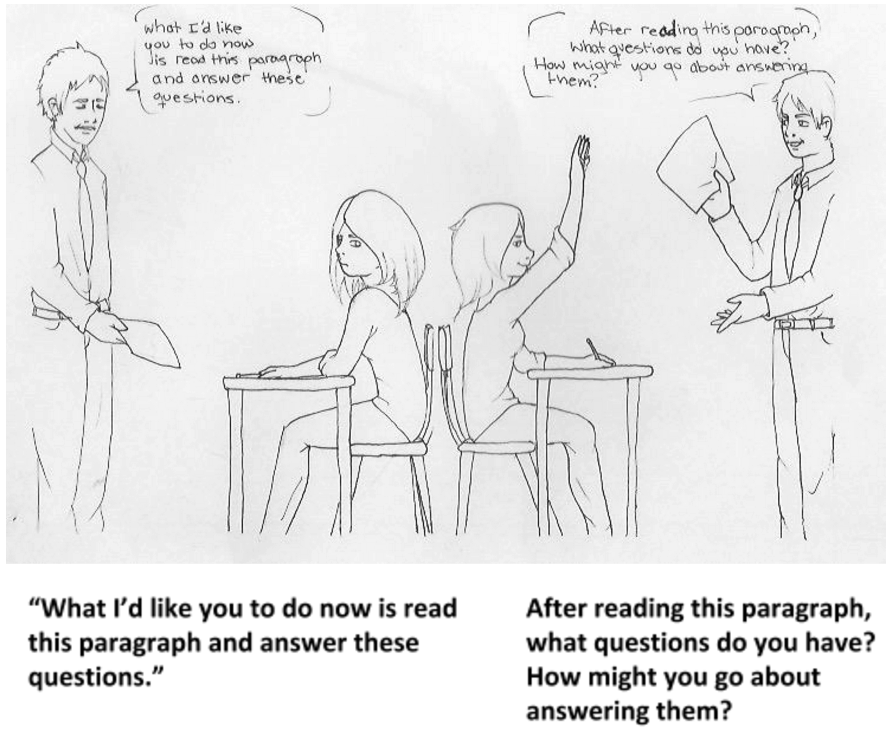

2. Encourage Questions

We take much better care of our own cars than we do rentals. Why? Because they are ours, we own them. It’s the same with questions! When we are truly invested in something, we are more interested. What are the learners interested in? Ask and allow them to follow their interests. It’s important to give people information before asking for questions and some reflection time, however. The Question Formulation Technique is a great way to start engaging students in question-asking and analyzing.

3. Connect the Learning

It’s not surprising that the mindfulness movement, standing consciously in the here and now, is a popular trend today. Our work in formal education settings is future-focused and imbalanced towards feeling like a chore rather than a pleasure. Learning is survival and joy! Mastering skills to enter the workforce is a survival skill. Translating letters to words and ideas on a page or coding something for the first time is joy. And often, they are one and the same. What is the purpose of the lesson or activity, besides a final grade or a test? How can we root our activities and learning in the present while connecting it also to the future? Every lesson provides ourselves with the opportunity to answer the big picture question: Why should we care and How does this connect with who and where I am right now?

Changing the way we instruct, whether it is in a formal setting (like a classroom) or an informal setting (like the family dinner table), will take time before it takes hold. It will require a different set of skills on the part of the ‘teacher’ and a radical new set of expectations on the part of the learner. But its potential to improve teaching & learning, two sides of the same coin, is undeniable.

Learn more:

- Designing Inquiry-Based PLCs to Differentiate Instruction and Drive School-Wide Improvement

- 3 Lenses for Developing Deeper Driving Questions

Kimberly L. Mitchell is co-founder of Inquiry Partners and a teacher at University of Washington’s College of Education. Follow Kimberly on Twitter, @inquiryfive. Her 14-year old daughter, Zoe Mitchell, created the illustrations.

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.