Leadership for Education Innovation

By: Michele Cahill

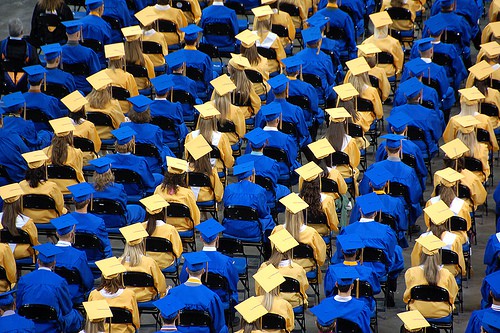

Educators have heard the good news this year that the United States has for the first time reached a high school graduation rate of 80%, with gains in large urban districts and among African American and Latino students as significant contributing factors. Reactions to this achievement have been mixed, ranging from celebration to cautious optimism to dismissal, the latter due to recognition that graduation does not equal college readiness, particularly for low-income students. At a time when earnings are tracking so closely with educational achievement and income inequality is growing, our young people will depend more than ever on schools to prepare them with the meaningful knowledge and skills needed for success in postsecondary education and careers. Without effective high schools, the social contract with young people that lies at the heart of the American dream–Invest in yourself, work hard and learn, and you will have opportunities for rewarding work and meaningful choices about your future–is clearly at risk. While there are broader, non-education factors involved in our country’s high rates of child poverty and growing inequality that need to be addressed, the stakes are high and the need is urgent for redesigning our high schools. We need to ask, as rigorously as we can, what it will take to get to 90% graduation rates with college readiness in the coming decade.

Fortunately, we have existence proofs that it is indeed possible to provide adolescents–even those who enter high school substantially behind–with an academically challenging curriculum and accelerated learning that enable them to catch up, get on track, and graduate ready to succeed in postsecondary education. Greg Duncan and Richard Murnane write about “High Schools That Improve Life Chances” in their recent book, Restoring Opportunity: The Crisis of Inequality and the Challenge for American Education, which profiles the New York City Small Schools of Choice initiative and its evaluation results. The evidence they cite is highly encouraging, especially now that researchers from MIT and Duke Universities have confirmed the original MDRC findings and are identifying positive outcomes in students’ first years of college.

Looking to implications for the country, the question is, What will it take to do this at scale? As someone involved in the New York City work and in high school reform more generally, and with more than forty years of experience in K-12 and higher education, youth development, and the nonprofit, government and philanthropy sectors behind me, I have come to see that an ecosystem for learning is essential; moreover, design thinking is essential for creating this ecosystem and for enabling it to work at scale. An ecosystem draws in energy and contributions from a broad base of leadership, including educators, advocates, policy makers, philanthropy, government and civic voices. To be effective, their efforts must be rooted in common design principles that guide them in creating good secondary schools that significantly improve life chances.

At the heart of an ecosystem for learning is an ability to draw upon the assets of an entire city or community to support students as they grapple with the two primary tasks of adolescence: building competencies and forming their identities. In New York City, this involved a competitive design process rooted in common principles informed by research about teaching, learning, the organization of schools, and youth development and resiliency. Educators who proposed schools had to engage in a rigorous planning and approval process, and their plans had to demonstrate the capacity to put in place core elements: strong and capable school leadership, a school culture that promoted positive youth development through caring relationships, high expectations for all students, and student voice and contributions; high-quality teaching across disciplines, accountability for all students, an academically strong curriculum, and parent and community engagement. Only teams that met these criteria were approved to open schools.

Where does the ecosystem come in? To meet these challenging criteria, we needed to redefine “school” as a porous organization and redefine “partnership” as a core design element, not an add-on. When partnership is a core element of school design, students have opportunities for relationships with adults and experiences that literally expand the world that is well-known to them through connections with cultural organizations, professional and business settings, science and technical organizations, or community services. Students have opportunities to take on new roles and try out identities that can motivate them and build confidence and effort. Partnerships that are designed as core to schooling also can expand and deepen curriculum through themes, project-based learning, internships, student research, and expeditions.

Design thinking gives real roles to partner organizations in a learning ecosystem. New approaches are pushing the boundaries, as digital and blended learning open up new opportunities for educators to think creatively about how to credit student work accomplished outside a traditional classroom in an expanded learning time framework. From an equity perspective, building a eco-system that affords access to learning opportunities that extend and enrich academics is highly promising, as economically advantaged families are dramatically increasing their investments in student talent-building activities and experiences in the out-of-school time hours.

Moving this agenda in a time of tight budgets and high standards is challenging. Yet it can be a powerful strategy for increasing student engagement and effort, for supporting teachers in meeting college-ready standards, and, most of all, for tapping the extra capacity we will need to get to college readiness at scale.

Michele Cahill is vice-president for national program and program director of urban education at Carnegie Corporation of New York. From 2002-2007, she was senior counselor to the chancellor for education policy in the New York City Department of Education under Chancellor Joel Klein .

Maureen

Great piece Michele! Budget is the most important thing when it comes to education as it's too costly and it will be more costlier after 5 years from now. I have seen many kids leaving school during their 8th and 9th grade as their parents couldnt afford paying tution fees. United states should have schools who couldnt afford paying fees or education loan with less interest.