“Keep Your 3, I Want My A”: What’s Up With Standards-Based Grading?

My local newspaper’s mission appears to be “cover controversy.” They only cover crime and criticism; they avoid constructive stories that build context. Unfortunately school grading policies is an easy target if you like controversy.

For the second time in twenty years, my community is arguing about grades–the first time I was superintendent. In 1994, Washington introduced expectations for English and math and I thought we should provide feedback on whether kids were meeting those standards. The change caused quite an uproar because 1) the expectations were higher; 2) the feedback was about what kids knew and could do, not attendance or extra credit; and 3) the reporting system was a lot of work and hard to understand.

You might ask, “What problem are we trying to solve?” The first answer is that traditional grading systems are inconsistent, often subjective and more about effort than outcomes; and not closely linked to the big goal of college and career readiness. For most secondary students, the goal is to figure out the grading game and do the least to get the grade they need.

Let’s back up and put grading into context. School districts with effective leadership are trying hard to embrace higher expectations and use new tools and strategies to personalize learning for all students. A paper I co-authored put it this way:

The current factory model of schooling – with its time-based, bell-curved grading system – will undermine all of our efforts to personalize education. No matter what standards we use, no matter the innovation, a conveyor belt model limits student achievement in two fundamental ways:

It holds back students who could be excelling. advanced placement, dual enrollment, and early college have created opportunities for students to progress beyond the limits of the K-12 system, but this only happens in the final years of high school. Students are held back to the predefined pace of their age-based cohorts throughout their elementary and middle school years. We’ve handcuffed our children and ourselves.

It moves on students who aren’t ready. Students who don’t get what they need are moved along, grade to grade, with bigger gaps in their learning each year until they no longer see a future in school for themselves or graduate with a meaningless diploma. Many who are retained still don’t get what they need. Credits driven by seat time put over-aged, under-credited students at risk of aging out of the system.

“The grading philosophy is one of the most important decisions,” the paper continues, “as it defines how students understand what is needed to be successful, but it’s really the promotion policy that is most important.” My local district was used as a good example of a district attempting to provide valuable feedback to students and avoid moving students along that aren’t adequately prepared.

Time to learn. School districts are trying to shift from time to learning–from moving kids along when they get a year older to progress based on demonstrated competence. iNACOL, where I’m a director, is the leading advocate for competency-based education. We sponsor an online community, CompetencyWorks, where educators share views on how to design better schools. You can find blogs on grading systems here.

Many schools use a 1-4 scale to indicate not enough evidence, not yet proficient, proficient, or exceeding proficiency. Parents and students may think this is just the same as A-D, but it’s not. Designing a grading strategy and communicating it effectively is an important step in reshaping the culture of schools and districts.

Much of the grading controversy is driven by college admissions. That’s slowly changing. Last week, 48 New England colleges announced that they would be accepting proficiency-based diplomas. While we’re waiting for higher ed to change, school districts will need to provide translations that give their graduates a shot at selective schools.

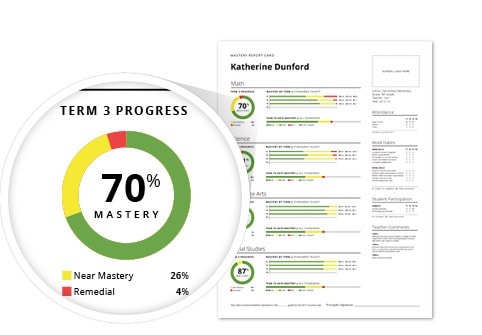

Report cards that provide standards-based feedback need to be simple to produce and easy to understand–and 20 years after our first attempt, it’s still harder than it should be. Fortunately, there are a few companies like MasteryConnect attempting to reinvent the report card and using simple data visualizations to chart progress.

Shifting from the grading game to reliable standards-based performance feedback is proving to be a challenge, but it’s an important part of an education system that embraces high expectations and personalizes learning for all students.

MasteryConnect is a portfolio company of Learn Capital where Tom is a partner.

Maggie

Our county just started this system only for K-2 students, while grades 3-5 (and above) are simply on a ten point scale with letter grades. How is that an adequate use of standards based performance for college and career readiness? Is there any explanation as to why my students in second grade are aiming for "all 4's" when next year they aspire for As and Bs? I also find it productive, sure, if one universal system is used in a K-12 setting. However, wouldn't a ten point scale be somewhat more accurate vs a scale which is based on a 25 point difference? I can see using MasteryConnect as a nice resource, but shouldn't our grading systems (ie PowerSchool, etc.) do this for us so that teachers can focus on student success and not having to wear yet another hat of 'translator' for parents once we have analysed our students progress with formative and summative assessments?

Angela Worcester

Mr. Vander Ark,

One FWPS parent shared your blog with me, and I plan to share it further with parents who have organized around our common concerns over the third and newest version of the Standard’s-Based Grading System implemented in September 2013.

Those of us at the center of a newly networked parent group feeding the local controversy have supported our district’s shift to standards-based education, and I see that many of our reservations with respect to SBE are addressed by the theory of competency-based education. Over the past four weeks, it has been difficult in the letter-writing campaign to the Board of Education Directors, the Federal Way Mirror and recent news interviews to underline our support of SBE while criticizing the current Grading System. Parents and students are angry. Anger is easier to express and much more entertaining.

I’d like to clarify, that, from my perspective, parents are up in arms over the grading system for the 4th time, the second being when FWPS first proposed a purely Pass/Fail Standards-Based Grading System for a pilot program, completely embracing the ideals of a proficiency-based diploma. This change did not fly with parents or students who quickly discovered that many college admission programs were not prepared to accommodate proficiency-based diplomas. The district incorporated this feedback and applied a B-A-M-E or A-B-C-F on top of the Pass/Fail system of assessing standards.

Of course, the third controversy arose when the pilot program’s grading system was implemented for the first time district-wide in conjunction with Standards-Based Education in September 2010. At the same time, three other controversial academic policies related to advanced programs, homework, and retake policies were implemented. In short, it was impossible for the community to separate their concerns over one issue from another.

Since then, I’ve had conversations with teachers, students and parents critical of the previous two versions of Standards-Based Grading Systems implemented district-wide. I’m assuming you may be familiar with the difference between the first and second versions.

Criticism centered on the correlation between grading proficiency and the district policy allowing/advocating multiple opportunities for students to retake assessments and demonstrate proficiency. A student who didn’t put forth much effort in mastering standards at the beginning, could cram, retake assessments and receive the same course grade as the student who worked hard throughout the duration and performed consistently on assessments the first time. High school students were disheartened to learn that one point was being deducted from their GPAs during the admissions process by local universities who evaluate our district as one with inflated grades and less academic rigor. I understand the district incorporated this feedback into version 3 of SBG in Federal Way.

I had my own reservations over the past three years regarding the implementation of SBE and the grading system and took every opportunity to share them with district administrators through various parent groups and meetings. Along the journey, my children have performed well, and their teachers have been able to clearly correlate assessments designed to demonstrate proficiency in standards (1-2-3-4) to resulting course grades (B-A-M-E or A-B-C-F).

And then, out of the blue, I received an email from a parent to watch the presentation of FWPS parent Mike Scuderi regarding the application of Power Law to the Board of Education on October 15, 2013. My husband and I were alarmed and started researching Power Law and Marzano’s theory. Next, my son received a 2 (approaching proficiency) on one assessment in the only academic course in which he is not challenged and can easily demonstrate exceeding proficiency in all standards. However, as he had misunderstood the directions for one assessment, a ‘2’ on one assessment affected the grade for one standard and turned an ‘A’ for the course (exceeding proficiency) into a ‘C’. Finally, I started comparing circumstances with parents of other high academic achievers to find that an alarming number of students’ overall course grades for the first marking period were being calculated as ‘2s’ and ‘1s.’ These were students who had never in their academic careers had difficulties demonstrating proficiency, students who often have to wait for their age-based cohorts to catch up so they can continue to progress as a class. Families with students of varying academic abilities suddenly could not ascertain whether a 'C' or 'F' on progress reports reflected proficiency, indicating students require more support, or was purely a miscalculation.

What was happening? Parents began networking to press hard for some form of moratorium on the new Grading System that was implemented in September to salvage our students’ first semester grades and avoid detrimental impacts on life opportunities after high school. We focused primarily on the misapplication of the Power Law equation to standards that do not meet the criteria to calculate growth over time as described in Marzano’s publication “Transforming Classroom Grading” (2000). And yes, we made entertaining noise for the media in order to combat the “stay the course” position we encountered in urgent requests to the school board to correct a misinformed decision to approve a complicated 4-layer grading system and the misapplication of Marzano’s Power Law.

Our students cannot afford to be used as live test subjects for grading system theories that result in undervalued grades. Moreover, the districts’ consumers cannot accept quick fixes to manipulate a complex 4-layered calculation just to produce more palatable course grades that fall closer to the average or a teacher’s professional judgment. How can a college admissions program evaluate a transcript from a school district where neither teachers nor students can explain how grades are calculated other than “it agrees with the teacher’s professional judgment?”

Thus, parents are working hard to partner with the school district and the school board to identify a viable solution within current software limits. We want the equations currently producing errors to be removed while respecting two of the district’s paramount goals: to focus assessment purely on learning and improve overall graduation rates by providing multiple, meaningful opportunities for students to demonstrate proficiency.

I welcome a shift in educational thinking and policy from the grading game to reliable standards-based proficiency. A perfect system will be fully funded and focused on learning. It will hold students, families and teachers accountable for knowing where a student excels and where they need support. However, from my perspective as a parent sorting through college admissions requirements, the shift towards proficiency-based grading and diplomas has to start from the top. When the most competitive higher learning institutions accept applicants who demonstrate proficiency and no longer consider GPAs a valid admissions criteria, parents and students will do everything they can to elect and hire leaders who can identify and implement a well-researched and validated proficiency-based education system in their home school districts.

In the meantime, I would value your support and input on how to solve the immediate grading system crises in your hometown and identify a plan to develop a Standards-Based Grading System for the very near future that honors the premise of proficiency-based education as well the role transcripts play in college admissions… taking into consideration, of course, our school district’s diverse challenges and limited resources.

I sincerely appreciate your advocacy for individualized, proficiency-based learning for our nation’s children.

Replies

Tom Vander Ark

Thanks for your comment. I don't understand the local issue as well as you do but will investigate further.

Rebecca Eaton

You comment about 48 New England schools supporting the proficiency based grading - as a point that colleges are starting to recognize these new grading systems.. Great! Did you look at the list? Not one top college among them...no Colby, no Bates, no Middlebury, no Dartmouth, no Brown. I could go on and on. So, if your child is looking for a middle to lower level college, this new grading system might be for you. But, it your child has high aspirations...good luck if they graduate in the next few years!

Replies

Tom Vander Ark

Thanks Rebecca, you're right, if you want to go to a selective college you need to play their game--but many are looking at broader measures. Brown says: "Rather than relying solely on a set of quantifiable criteria like grades and test scores, our admission process challenges us to discover how each applicant would contribute to—and benefit from—the lively academic, social, and extracurricular activity here at Brown. We will consider how your unique talents, accomplishments, energy, curiosity, perspective, and identity might weave into the ever-changing tapestry that is Brown University."

They may still need to produce a GPA & SAT, but I think every student should leave high school with a portfolio of their best work, a list of work experiences, and a collection of references. It will serve them well where ever they go.