Town Hall Recap: Microschools: Sustainability, Scalability and Accessibility

On this Getting Smart Town Hall we provided an overview of our microschooling initiative, unpacking three emerging themes: sustainability, scaling, and accessibility. We were joined by Coi Morefield of Lab School of Memphis and Julia Bamba of Issaquah School District who shared some of their many learnings from running microschools.

Links:

- Getting Smart Microschools Campaign

- A Big Push for Small Schools

- The Lab School of Memphis

- Issaquah School District

- Black Mothers Forum

- My Tech High

- ASU Prep

- Khan World School

- Global Online Academy

- Snoqualmie Valley School District

- Launch Microschools at Stedman Elementary

- Gem Prep Online

- Laguna Prep High School

- UNC Lab School System

- GPS Ed Education Center

- Update on ESA Funding from The Learning Counsel

- Enrollment Projections from The 74 Million

- Getting Smart on Place-Based Education

- EdChoice Summary on ESAs

- Podcast on GOA

- Mysa School

- Christensen Institute on Microschools

- Arkansas EFA Details

- Embark Education

- PBS NewsHour Feature on One Stone Lab School

Annotated Transcript

Victoria Andrews: I’m Victoria Andrews, and again, thanks for joining us as we have a community conversation on microschools, sustainability, scalability, and accessibility. I will be joined by some of my GettingSmart friends, Jordan Luster and Nate. We’re also joined today by two great friends of Getting Smart, Julia Bomba and Coi Moorfield. Coi is the lab school’s founder and executive director and is based out of Memphis, Tennessee. Julia is a member of the Issaquah School District and is now in the role of secondary innovation. She was a former principal at one of the high schools in Issaquah that we absolutely adore and love. That was super instrumental in getting the students out into the community and giving them internship opportunities and just really rich learning experiences.

So we are getting to know Coi in this space, and we’re super happy to have both of you guys joining us today. I’m going to let them both share and give a little bit more information about their schools and how they function as microschools.

Coi Morefield: Thank you so much for having me. I am thrilled to be here and in such great company. I see some friends and community members, friends who have become microschool family, who are here as well. I’m really excited to be a part of this conversation. I am based in Memphis, Tennessee and founded the Lab School of Memphis. We serve pre-K through 8th grade learners, focusing on centering learners in addition to equipping them academically, also focusing on community-based learning and project-based learning. So ensuring that we’re cultivating real skills for real life.

So whether that’s forest school or through internships at the middle school level, we’re really connecting our learners to community experts and all of the knowledge and future possibilities that are available to them right in their communities. These diverse pathways that we are hoping to help them shape as they go with the goal, honestly, of community development. We’re a school, but at its core, we are looking forward to developing people and communities.

And that’s right on time with what we just mentioned in the program. So we love that. And we’re anxious and eager to hear and learn more about the Memphis Lab School.

Jordan Luster: Julia.

Julia Bamba: Hi. Thank you so much for having me here today. I see a lot of familiar and friendly faces, as Victoria shared. I’m in the Issaquah school district, about 20 miles east of Seattle. We’re a school district of about 20,000 students, a pretty traditional learning environment. After spending seven years as the principal of Gibson Eck High School, we just cooked up all good things about learning that we really want students to enjoy and experience. Personalization, student agency, interdisciplinary learning. Students spending two days on internships every week.

And while that’s incredible and available to 200 students, in my new role, I’m trying to break into our traditional system and see how we can take all of that goodness and learning that we want our students to experience that we know is relevant and important in their lives and developing them as people and connected to their future. How can we start to get into our traditional system, stir things up a little bit, help our educators think differently about what learning can be for our students and put students at the center. So with our microschool that we have just started in the last few months, it’s in one of our comprehensive high schools that is a school of 2500 students.

And so we have a small team of incredible students who have joined our microschool and they learn through interdisciplinary learning, project-based learning. Our huge goal is to just get them out into the community. They’re earning environmental studies credit as well as English credit. So, for example, taking the kids rock climbing and hiking in North Bend on Friday, just helping them see that learning doesn’t have to always exist within the classroom and as they know it, how can we help them experience learning in a different way that’s meaningful?

Victoria Andrews: Thanks. And we’re huge fans of place-based learning and project-based learning here at Getting Smart. So to hear that’s happening in a school within a school model, you’re just giving us, you’re hitting all of our levers. We’re just, we’re loving that and we are super grateful to have you here again, Julia and Coi. Next up, we’ve got Jordan who’s going to share a little bit more about what we’re doing internally to help support microschools.

Jordan Luster: So the last time that we hosted a town hall discussing microschools, the discussion was framed around how microschools can lead to macro change. And we talked about how microschools create new options for families, how they can be used to quickly address underserved populations, and how they’re basically a catalyst or vehicle in starting innovative practices. So since then at Getting Smart, we focused a lot of our efforts in supporting microschools with an emphasis on just that high-quality, innovative models that are serving historically marginalized and underserved communities. We understand that the creation of microschools can lead to inequities and we’ve kept that at the forefront of all of our efforts and our microschool initiatives, including facilitation of community practice strands, providing coaching and technical assistance, and most notably, our funding efforts.

Last year, in the fall, our Learning Innovation Fund partnered with Walton Family Foundation and launched this big push for Small Schools grant program. And our mission was basically to foster a network of microschool leaders by offering grants to propel the development of their innovative learning spaces. And we’re focusing on operators who were looking to scale their high-quality models. For our first round of grants, we selected a very diverse group of grantees who’ve been making incredible strides and impact and growing and expanding, many of whom are on this call today. A couple will be chiming into the chat to answer some questions, so hopefully, you all will get a chance to connect with some of our grantees today.

But it’s been really great working with such a dynamic group of microschool leaders through these initiatives, we’ve learned a lot about the sector and the landscape, and we’ve learned that sustainability, scalability, and accessibility are the emerging key themes within the microschool landscape right now. So we wanted to dive into it and talk a little bit about that today, some of the opportunities and challenges that exist within those themes. One thing that has been clear in our findings is that microschools are not monolithic. They are existing in both private and public spaces, and they encompass a variety of small school models under that umbrella of microschools, which Nate’s going to talk a little bit about.

Nate McClennen: All right, so let’s take a pause for a second and think about the ice plunge or the cold water plunge in the chat, because I think it’s a great analogy for microschools is that I’m quite sure that we have 81 people on this town hall and that the vast majority won’t appreciate the cold plunge. But there are a few on this call that appreciate the cold plunge. And this is a great analogy for microschools, right? So microschools are trying to serve more learners in different ways so that every child is able to succeed, and we’re not, we all know we’re not quite there yet in the existing system. So we’ve been doing a lot of work trying to map the ecosystem.

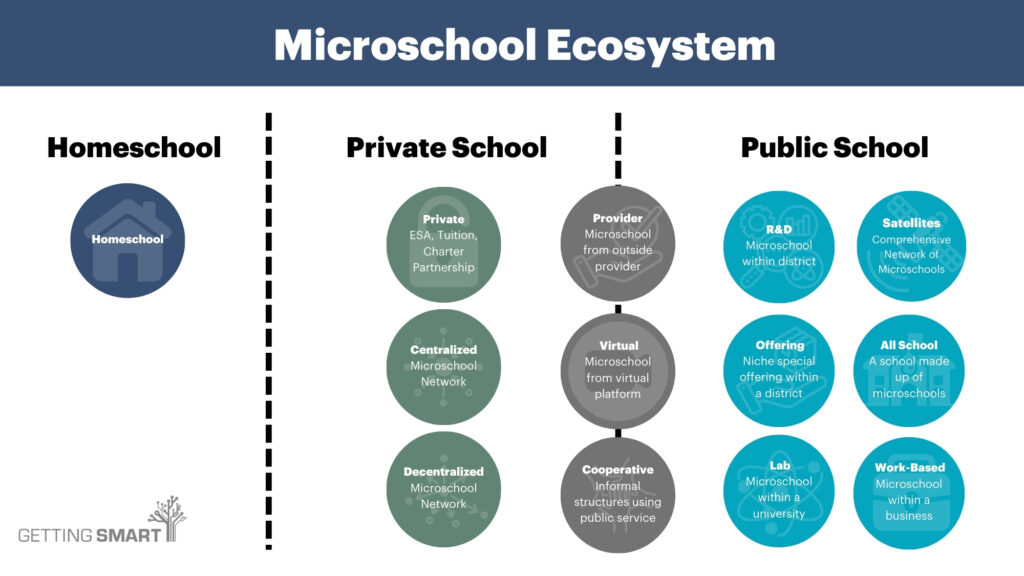

We feel that there’s a lot of people thinking about microschools and defining microschools and saying microschools are this and microschools are that. And we’re sitting back on the broad definition that Jordan provided in the beginning about personalized, learner-centered environments that are less that they’re small in size and we’re seeing as we map it, that there are a number of different types of microschools out there. So clearly there’s the homeschool environment that could be categorized as a microschool, the private school environment, not all private schools, but there is a number of microschools that sit within the private school sector in terms of whether they’re tuition-charging or tuition-free or ESA funded, even chart public school charter partnerships. And then Jordan alluded to the centralized or decentralized networks of private microschools.

So that whole ecosystem is blossoming right now. And then on the blue on the right, there’s a huge sector of public school microschools that are out there, those that are creating them for R and D. So you create a microschool in your district, perhaps like Julia’s thinking about, to help spread innovation in a district, specialized offerings within the districts, lab schools that are based in the University UNC, University of North Carolina has an extensive lab school network that all could be considered microschools that are focused on developing teachers and innovative practices. Certainly work-based learning co-located in corporations. So GPSED is an organization that really provides spaces for businesses to host students in their business locations to help develop skills around the CTE world. There are schools that are made up of all microschools in the nineties and the early two thousands.

The school within a school and the academies model was an example of that. And then newer versions of we’re calling satellite microschools. So gem prep learning societies, ASU prep, Purdue Polytech, they’re all thinking about how to take their model and replicate it in smaller little geographic locations. And so we know that this map isn’t perfect yet, but what we’re trying to do is better understand a big tent view of microschools. And so a couple of our conclusions. One is that we all have to acknowledge that microschools are not new. There have been microschools in sort of rural public ed for years and years. There’s been homeschools for years and years, small private schools within a school. So it happens to be getting a lot of attention, but there’s a lot of great history we have to go learn from and acknowledge.

I think what’s new is that there are new formats, especially with the ESA, a lot of growth and a lot of attention. So those are the new things that are happening. And so this big tent definition we think serves more learners. And Jordan and I are authoring a blog right now. We’re going to try to extrapolate on this a bit more with a lot of different examples, and we hope a lot of you will read that and then ping us back and say, no, you missed it here. You got it here. To help develop a bit more of a universal understanding of what are microschools for all those that are in education, but also those that are outside of education that are using that term. So a couple big trends that we should all acknowledge. Obviously, ESA funding is on the rise.

19 states have ESA legislation, another eleven considering passing. This is causing the proliferation of microschool opportunities where public dollars can flow individually to families and or students to go then put into funding the private microschool sector. Interesting phenomena that’s happening and something that we need to pay attention to. And the second thing is that public school enrollment is on the decline. And while some folks have said it’s because of the rise in microschools, I actually think the demographics would suggest that really were experiencing a birth rate decrease. And there’s a great article in the 74, I think yesterday or the day before that did an incredible analysis of projections moving out over the next decade. And so there are going to be enrollment declines.

And so that provides a warning for, I think, those that are in the public sector saying, oh, how do we deal with different budgets and enrollment decreases, not only from COVID but just general demographic changes, but also an opportunity for everyone to think about. How do we create incredible learning opportunities to attract and retain the learners that we have, whether it’s in the private or public sector? So two, a couple things to think about from a landscape point of view that we are thinking about in partnership with our grantees.

Victoria Andrews: Thanks for sharing all that, Nate. And like he said, we’re super excited to have any kind of feedback or just poking holes or even sharing your curious thoughts. In regards to the graph that he shared earlier about microschools. We that’s a constant conversation of just like what does it mean, what does it look like? And then the different schools that are falling into that. So we’re going to dig a little bit deeper by touching on sustainability and scalability and accessibility when it comes to microschools. So some of the factors that are impacting microschools and that we’ve noticed in conversations are just their business model structure. What’s their value add to their community?

Sustainability of Microschools

Victoria Andrews: First of all, being knowledgeable of their community so that they can, maybe they are in a rural location and they’re trying to offer more hands-on, real-world learning for their students. It might be that they are in an inner city. And so they are building a microschool that is targeted towards unhoused youth or youth that have been historically marginalized or overlooked. And so what is the business model structure? What are they going to contribute that’s not already in existence or that is even of greater value to the community? Key factor is just the ability to build and maintain those partnerships, because microschools cannot operate alone. And both Coi and Julia have mentioned several times how it is key that they just plug into those partnerships and really capitalize on them to continue to sustain the amazing work that they’re doing.

Also looking at operations, microschools, this is key is just how are they, when are they going to do it? Where are they going to do it? The building? If you’ve ever worked in a traditional setting, then you’re very familiar that operations and transportations, that tends to be some of the highest expenditures. So those don’t go away for microschool leaders and founders. So they often look at going into joint agreements with other partners and maybe even splitting some of the costs and the share and the burden of that. And I know that’s something that both Julia and Corey are going to be able to share about in a little bit too. Also just where they located being super creative and looking at places that are not being used during typical school operating times.

So places like libraries or places of worship, or even like spa, which operates out of goodwill. So partnering with other nonprofit organizations and using their shared spaces as being a real smart way to defer some of those, the costs in regards to buildings and then staffing. This is something I really want Coi to discuss. Just being real smart and creative about staffing and just bartering staff in partnership with the local public school. Coi, can you share a little bit more about that?

Coi Morefield: Sure. So I’m sure that most here have either experienced or anticipated experiencing issues with appropriately staffing their learning environment. One of the things that we did this year and sort of getting creative is we needed someone in the studio working face to face with learners who had a strong background in support around academics. In middle school, were not in a position to bring in another full-time person, and I was connected with a veteran educator who began a tutoring company and was still trying to build traction and get it off of the ground.

And so what I offered, I outlined an MoU, a memorandum of understanding that she would come in and support our middle school group in the mornings around academics, but also building community, getting them started for the day with their morning invitations, and in exchange we would allow her to use our space for tutoring. So she then had an amazing space, a beautiful studio that had lots of resources and manipulatives that she could use free of charge. She had access to our wifi, to our printer, our office space, so that she could then build her business. And of course, being present here, she also had access to our community for any learners who may be interested in outside tutoring. So were able to leverage her vast experience and skills as a reading specialist and a veteran educator while also supporting her.

Victoria Andrews: So it was a mutually beneficial relationship that didn’t require the exchange of any financial resources, and that is huge because it served both her and both you. So I love that example of just being able to barter both space and skills and just microschools having that in order to sustain a program and to sustain, you know, just even how money is being used and allocated towards staff, being real creative and innovative in that. So some of the challenges that are facing some of the microschools that we’ve discussed, and we’d love to hear more that you can think of in regards to sustainability. Our enrollment.

As Nate mentioned before, if the basically for lack of the number of students that are available for microschools have just declined with birth rates, then how are they going to meet that need, the financial structure, some of them, if you’re not in an ESA state or you’re awaiting ESA legislation, how are you going to fund the microschool? Is it going to be through grants? Is it going to be through private donations? Endowment? What is that going to look like of closing schools? We’ve heard that schools are closing both in the public, private, all over the country based on enrollment and other factors. But within the case of microschools and other learning environments, the perception of closing the school doesn’t necessarily have to be noted as a failure. Maybe you’ve sustained the purpose that was necessary for that duration.

And so based upon community need and whatever the case may be, just that perception of closing a school as not a failure, but that it served its purpose for that duration in time. And then also the policies. I know that some people have mentioned already some of the policies that are state related that serve as challenges and barriers to the sustainability of microschools. So some of the opportunities were intentional partners or our intentional partnerships being very strategic, looking at again, community needs.

Is necessary for young people to be successful and for parents to have that trust in that community, and then succession planning being very wise about how do we plan to carry on? Is it just for a limited time. If it’s only for research and design, then maybe the goal is not to have a microschool for 20 and 30 years. Maybe it’s supposed to just serve as how can we grow this so that it can be impacted on a larger scale. So I’d love to hear any other challenges or opportunities that you might think of when it comes to sustainability. You can drop them in the chat or come off of mute as well. And then we’re going to prepare for some discussion questions. So what innovative strategies can micros employ to continue their impact without compromising their school identity?

And Coi and Julia, if you guys want to share some of the things that you are already doing, you can do that.

Julia Bamba: Yeah, I’ll go ahead and jump in and just share a little bit about the school identity. I think using what we’re using our microschool for now is trying to test the innovative learning strategies. Things that we know are not experiential, they’re research based, they’re good practices that we wish that all students would have. And in trying to sustain this in a larger, comprehensive high school, through the school within a school model, is testing these and helping other adults in the school building see that these practices are incredible. It also allows an ability. So we’re running through competency-based learning. So any teacher in our district has the opportunity to set up their gradebook through competency-based, but very few do it. And so this is a way for us to show that our students are still demonstrating the skills that they need.

They’re just doing it in a different way, not through the same content delivery, but they’re able to do it through creating portfolios and collaborating on projects in our community. So those are a couple things. The other thing through our small pilot right now is that we’re able to have, like, as Coi was saying, how do we use staffing in different ways? So we have on-time grad specialists that they are working every day with students, but how can we leverage their time and their experience and have them now in the microschool teaching? And then as we sustain and grow this, how can they then become coaches and mentors in the building as new staff?

Take this on, and not only think about it as a microschool, but then why do we not have other courses that then become interdisciplinary, real-world learning courses, not just through the microschool? So this is really like, how do you spark ideas? A lot of times in our traditional systems, people don’t even know it’s possible. And so how do you create this identity of like, this isn’t just a microschool over here. They’re doing this. They’re the only ones that can do this. It’s like, no, anybody can embed these practices into their school design. They can embed it into their daily classes and courses. And so how do we generate excitement? It generates sparks around that and then continue to grow and create mentors within our staffing model that can help inspire and coach along the way.

Victoria Andrews: And I love that you guys are using it as a hub of innovation to grow. So that when we talk about equity, as Jordan mentioned before, that’s at the forefront when we’re talking about microschools for us here at Getting Smart. And so that’s a real strong equity play to make sure that it’s not just those students that are in that microschool that are experiencing it, but how can you expand it to a larger scale?

Nate McClennen: Just thinking about sustainability. Love to hear Scott Van Beck come off for a second. Just talk about the limitations of ESAs, because I think they appear to be monolithic in the news, but really they come in a lot of flavors and shapes and sizes. Yeah.

Scott Van Beck: Thanks, Nate. I think we just need to be clear that just because the state has passed ESA legislation doesn’t mean that the opportunities are wide open for out of school opportunities. A lot of these states, their ESAs are only qualified if a family decides to move from an established public school to an established private school. And so, you know, we really need to work hard with our policymakers and our politicians to make them understand, to really open the gates wide. Microschools, learning pods, homeschools, all of these out of school opportunities need to fall within the confines of ESAs.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. So that variety matters. And I think that’ll have an impact on, especially the private ESA-funded microschool sector. Again, one part of the larger microschool sector.

Jordan Luster: And I think just to add to that, one of the barriers here is that legislators are looking for schools that are accredited and microschools, you know, a lot of microschools have opened to kind of come out of that box that accreditation can sometimes place these different learning systems in. And so it’s almost like, how do we be, when we’re talking about, I saw a few people in the chat discussing accreditation, how do we balance accrediting microschools while also allowing them to maintain their autonomy and flexible nature to provide that personalized learning? So if anybody wants to comment on that or share their thoughts.

Coi Morefield: So our school is accredited and in our state there is a short list of accreditors that are approved and I would recommend before assuming that accreditation will put you in a box, you know, do some shopping around, like do some research, do some, I don’t know, interviewing so to speak, of some of these accreditors. We have a fantastic relationship with our accreditation agency and specifically the evaluators who work directly with our school. They’ve been incredibly supportive. And also the directors that are here in our region formerly worked for our state. So they’re extremely knowledgeable as well.

So I would say that beginning to shift in the mindset and maybe look at the accreditation agencies as sort of an ally and a partner and just doing some research and getting educated before maybe entering into that process could be helpful, I think, in selecting the right fit for your school. It doesn’t necessarily have to be limited.

BB Ntsakey: Coi, I just want to give you a huge shout-out for how clearly you separated accreditation and what’s out there. And I just want to add one piece here because we’re here, Misa, and went through an accreditation process and what that process has taught us is that accreditation process, a process that isn’t as relevant to what we’re doing with microschools. And so I think the question that we’re posing and asking to sort around is how do we like this community that’s here? How do we sort of say what accreditation means to us, especially given that what traditional accreditation has meant and the sort of hoops people go through all things that are not relevant to us and the children we’re serving.

And so also one innovation, one strategy for us to really consider and bring together is how do we sort of say what our core pieces of accreditation process is so that we can get more of us through that process. Because as the process stands now, it is definitely beyond a burden for schools to go through. And it’s also going to ask for resources that we can marshal to other places. And so I guess the sort of question back to you is this, which is how do we, how does this microschools, community, right. How do we say what accreditation is? Is it having a certain competency-based approach? Is it place-based? What are the things?

And I think if we can begin to say what those are, we’ll have a really beautiful accreditation process that is much stronger than what folks are experiencing now.

Victoria Andrews: And real quick, BB, where are, what’s the name of your microschool and where are you guys, what state are you guys located in?

BB Ntsakey: Yeah, we are Mysa schools from the People’s Republic of DC. The district is here. We also are in Vermont, see this energy, you’re going to get this right. This is DC, this is Vermont, this is Mysa.

Coi Morefield: Yeah, I think, and I was mentioning in the chat when someone talked about accreditation sort of for microschools and I said I am so here for that and would love for us to come together and outline that. Like what does accreditation look like? But I think that there are, unfortunately, I guess I will say I do think that those are two lanes, not that we can’t travel both in tandem. Like I absolutely think that we should work on that and would love to be a part of that. But I think for existing schools now, particularly those who are required to be accredited to operate as private schools and are required to operate as private schools in order to access ESA funding, like that practical standpoint I think is, okay, well then how do we make this less awful for us as a process?

And I love what BB said about like sharing those resources. Like I’ve been through the process, I am happy to support so that other microschool leaders do not have to lose as much sleep as I did being the only non-student-facing person in my building during that process. So I do think that this sharing of resources, supporting and collaborating around that process, you know, for the practical side of it, like okay, until we have this place and get it accepted by states, how do we get through the necessary route to increase accessibility for our schools and then at the same time thinking through how do we establish a more formal system within our community?

Victoria Andrews: I’m going to pass it on to Jordan and she’s going to give us a little overview on scalability.

Scalability of Microschools

Jordan Luster: I think when we talk about sustainability and sustaining microschools, sometimes scaling gets coupled in with that. And you know, our last town hall when we discussed like how do we move microschools to, you know, move from microschools to macro change and creating that macro impact and you know, how can we kind of, how can we move this along a little bit faster? And I feel like that’s happening now. But the question, I mean, I think the answer is scaling microschools. And when we talk about scaling microschools, the question is almost always, well, what do you mean? What does it mean to scale a microschool? So some might think growth and I think that they are definitely, they work together, but they’re different.

So growth in microschools is just referring to the process of increasing enrollment, resources, and educational offerings. This might be like adding more teachers or expanding families, introducing new programs that, you know, meet the needs of your growing student population. But when we talk about scaling, we’re really talking about expanding reach and impact of the entire educational model. And so that might be increasing the number of campuses or enrolling more students, at times developing partnerships with other educational institutions. And I think this all ties back into how you sustain your model. So one thing that we’ve observed is that there is an increased demand for innovation and personalized learning options. So inherently, microschools being, you know, this growing movement, the demand for them has increased. Unlike traditional schools that might just scale through enrollment, this isn’t always the goal for microschools.

They want to remain intentionally small. So what does that look like in growing or scaling your model while preserving the uniqueness and the small by design intentionality? Many different microschool leaders are scaling in different ways. Right. We have learned that there are two major ways that microschool leaders are thinking about scaling into networks. And one of those ways which we kind of touched on earlier is decentralized, and the other is centralized. So when we talk, you know, independent, small microschools who are, you know, they’ve created amazing school models that are so specific to their community, they don’t see, you know, they don’t have a desire to scale that exact same school into multiple sites because it serves a very specific purpose, but an option. And what a lot of them are doing is codifying their framework to be replicated by others.

And this is more of a decentralized type of scaling. And so I heard a leader at a conference recently say, our focus is scaling deeper and not wider. And I thought that was a really great analogy in her attempts to scale through this decentralized method. And what it does is it provides autonomy to tailor the school model to the community, which is what we want, but there’s a risk there in quality control. And so how do we control for quality of a model? And a lot of microschool leaders are doing that through centralized scaling and scaling into more centralized networks that open and operate multiple sites. And they are able to oversee the operations of what’s happening at each one of those sites to make sure that the quality is there.

And so I wanted to, I want to open this up a little bit and discuss, you know, your thoughts on decentralized and centralized types of scaling. I know that Coi is currently, she opted for the centralized method, and I’d like to know a little bit more about that. What factors kind of led you to choosing a more centralized network?

Coi Morefield: For us, the impetus was the question, how do we get these community-based satellite studios or replications of our studios into communities who experience, whether it’s transportation barriers or financial barriers? How do we get our studios onto the block or the next block or the end of the block within walking distance right there. How do we address the barriers? And we’re still offering what parents in every community are looking for, which is that highly personalized experience focused on accelerating learning and a future-focused lens. Right. Because I not only want you to learn today, I want you to have a secure future tomorrow. So how do we bring that right to door or the end of their block? That was our goal.

So given that went with that sort of centralized approach because we felt that was the most direct path to ensure that were able to address those barriers, because with that approach, our accreditation, as I just mentioned, goes with us. Our status as a public private school in the state, that comes with us, our ESA approval, that goes with us. So there are all these things that are embedded and included that we take with us into these communities when we establish these satellite studios without a lot of extra paperwork or applications and processes, we are also able to scale our resources that way with that centralized approach. That means that the resources come along as well and quite frankly, are more attractive for the people that we partner with.

So whether it’s Olympic training center, which is here locally, or ASU from all the way out in Arizona, whether it is Nextdoor, the neighborhood app that we partner with, or the Pacers Athletic association and their G League team, the Bad ants, it is attractive to our partners for them to understand just how far their reach and their impact are going as well. And then that also means every community we touch, these resources that we feel are valuable, which is why we partner with them, are also touching them. So that was an important part of that, too. How do we get what we do here, what we have here, into as many communities that are demonstrating the most urgent need as possible?

Jordan Luster: Thank you for that. I think that’s what makes community-based schools so important is that you said, like, they’re all of the different pieces of the community that they’re touching through building of partnerships, our grantees are scaling as well, and not just in private sectors, but in public sectors as well. So Julia’s on the call. She also has been thinking about how to use microschools as a way to scale out innovative practices, and she touched on that a little bit earlier. But we are seeing tons of growth in the number of students that we’re touching and impacting. And so we’ll continue to publish updates on these numbers. But here’s just a glimpse of how many sites and students that are growing from last year to this year.

Nate McClennen: Mark asked a good question just to see if Julia has any comments about how microschools and districts so this public version can lead to broader transformation. So what’s the diffusion of innovation? Julia, in your experience, from what you’ve seen in landscape or your own school.

Julia Bamba: I think we’re a great example of trying to expand or transform a system. So starting with our choice school that started with 200, and we realized these are things that are really working for our students, especially students who are at risk or come into high school, who are hating school, who just want a different style of learning. And so taking what we learned there and then bringing it to one high school, our dream and our goal would be that we have a microschool within each of our three comprehensive high schools and then also expanding into our middle schools. So starting with one or two of our middle schools and then growing to all six of those, I think the important piece of this is what we’re seeing.

I experienced this in our choice school, and I’m seeing this now with our kids, is how do we use our students and their experiences to tell the story. And so we can do what we talk about learning that we want, but it comes to the students. It’s like, what is it that they’re seeing that they’re given the opportunity to do that no one else in their school is having this chance to. So it’s not seen as different, but it’s important. And other students are looking to it. When we started to reach out to students to invite them to join the microschool, what started happening was one would come and say, yes, I’m in, and I’d like my friend to join as well. And so there was this energy around.

School can look different, and we need to help students see what that vision is. And so again, this is a way to be able to provide a different experience for our kids so that they can see learning differently, so that they don’t have to see that they have to drag through seven periods a day. And it’s a way to test different learning models. And then how do we help expand this across the system? And the biggest thing not only is that student voice, but then the adults who are part of that, and how do they help tell that story? How do they become leaders?

How do we give students agencies so that they are seen as mentors and leaders, and that they’re the curators of this, of the microscope, and that they are the ones that can help us transform it and we as adults are there, you know, to help corral and to help make sure that we’re meeting the, you know, our district mission and what we need to do. But the kids are the ones that can really help us grow this.

Accessibility of Microschools

Nate McClennen: So maybe we close this section to think about hash student learners as curators. Right? Like that’s what we really want to get to. So Jordan, I’m going to flip to this last section, if that’s okay, and just do a quick, not in terms of importance, but really thinking about accessibility, because I think there’s a lot of big questions out there. And the reason we’re talking about a big tent and the reason we’re giving examples that are both private and public is we really want to make sure we’re thinking about accessibility. Every learner in the country or across the world should have access to a microschool if they want to participate in a microschool, and we’re far from that right now. So I think the things we need to think about are financial.

So tuition or tuition-free if it’s in the private sector, really accelerating public models. So where are the microschools in the public sector really thinking about ESA and how ESA is used wisely and more expansively and perhaps all sorts of partnerships in between there. So public and private partnerships could be a good part of this. And that’s especially in terms of services. We’ve seen some good examples of public services or public schools serving private schools or private sector educational opportunities, and the opposite private sector opportunities serving public schools. And I think we need to create a bit more of diffusion through those barriers between public and private to make access increase. Geographic is important. So are there virtual, hybrid or physical locations? I do a lot of work in rural and there are some microschools in rural.

Often the school itself is a microschool. But how do we make sure that in places that don’t have high densities of resources, young people, families, etc., how do we make sure they also have access to the microschool opportunities? I think staff quality and quantity is that I feel for the single leader, perhaps Julia and Coi, you both feel this way sometimes where you’re leading, but you’ve got a small team, you’ve got a program that you have a strong vision for, but it gets tiring after a while. So how do we make sure they’re sustainable in that way? And that affects accessibility and then breadth of services. Right? So microschools have to be able to serve all students and not just some students. And so we have to think about learning differences and students that are on IEPs.

If they’re in the public sector, how do we make sure that they’re accessible to all? So certainly challenges around cost and location. And really, the opportunity is that ultimately we have a model that every learner, a model for every learner that has strong culture and climate and every relationship that people are looking for so that students can grow and reach proficiency and feel like they belong in all scenarios in their schooling. And we know we’re not there yet. And I think microschools are a big leap in that way. So I’m going to pass it back. I think we’ll skip the discussion on this. Feel free to definitely throw things into the chat. Thanks, Rebecca. Around transportation, super important, and I know some schools are working on that, but I’ll pass it back to, I think, Jordan or Victoria to close us out here.Victoria Andrews: Again, thank you to our amazing guests, Coi and Julia. Thanks for sharing your lived experience of microschool founders. And thank you to everybody else who came on and just shared. Hope you guys have an amazing rest of your day.

Jordan Luster

Victoria Andrews

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.