Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann on Teaching and Updating Economics in High School

Key Points

-

Educators are encouraged to incorporate regenerative economics principles into their teaching, even if it’s just one lesson or part of a lesson. This can be done through project-based learning, community engagement, and exploring alternative economic models.

-

Teachers are provided with innovative resources like a comprehensive regenerative economics syllabus and related materials that they can freely adapt to fit their specific curricula. This allows educators to introduce new economic thinking even within the constraints of traditional syllabi, utilizing project-based and place-based learning to make economics education more relevant and transformative.

Are you looking for even more ways to learn in community? Check out the forthcoming webinar from the Aurora Institute. Learn more here.

On this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, Mason Pashia is joined by Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann to discuss a new approach to teaching economics and why it is critical to teach economics to K-12 students as a way of understanding the world.

They begin with Jennifer explaining the need to shift from traditional economic models, which often neglect the role of households, the state, and the commons in the economy. By incorporating regenerative economics in a K-12 curriculum, students learn about the importance of sustainability in economic practices and also gain a new lens with which to understand how and why the world operates the way it does.

The discussion also highlights the innovative principles used in creating the regenerative economics curriculum, such as facilitating change from the ground up and nurturing interconnection. Jennifer shares her journey of incorporating these ideas into her teaching and curriculum development, emphasizing the importance of project-based, place-based learning, and community engagement. She encourages educators to integrate even small parts of this new curriculum to foster a broader understanding of the economy among students.

Bio

Jennifer Brandsberg-Engelmann has worked in various roles since 1997. Jennifer began her career as a teacher at Walter Johnson High School in 1997. In 2001, she moved to ICS Inter-Community School Zurich and worked as an IBDP Economics Teacher, supervising IBDP Economics extended essays. Jennifer then moved to Frankfurt International School in 2007, where she worked as an IBDP Economics and Humanities Teacher, delivering day-to-day lessons and joint assessments and supervising IBDP Economics extended essays. In 2011, she was hired as a consultant at Avenues: The World School, providing curriculum advice for Humanities and the World Course. In 2012, Jennifer joined Strothoff International School, where she held various roles, including Lead | Sustainability Action Lab, Lead Curriculum Developer, Youth Mayors Erasmus+ Project, IBDP Business Management Teacher, IBDP Environmental Systems and Societies Teacher, Pamoja Education Site Based Coordinator, IBDP Coordinator, Chair, CIS/NEASC Accreditation, IBDP Economics Teacher, eLearning Coordinator, and Head of Individuals and Societies Department. In 2019, she became an IBDP Economics and Business Management Textbook Author for Kognity. In 2020, Jenifer co-founded the Frankfurt Doughnut Coalition and became a Teacher Contributor (Voluntary) for the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL). In 2022, she began working as a Freelance for Tomorrow University of Applied Sciences.

Links

- Regenerative Economics Course

- Link to the course

- Recent Webinar on the Regenerative Economics Curriculum

- Doughnut Economics

- Kate Raworth

- GCSE Requirements

- Revised GCSE Syllabus

- Mason’s Biomimicry Blog

Outline

Mason Pashia: You are listening to the Getting Smart Podcast. I’m Mason Pashia. Over the last few years, I’ve been digging into tons of resources about futures thinking and regeneration. Along the way, I’ve been thinking about how we might reimagine agreements and economies. And along the way, I bumped into something called donut economics, which is a line or circle of thought that celebrates new possibilities and how we can better care for each other and our planet. Today, I’m excited to chat with Jennifer Bransburg-Engelman, a longtime IB educator who has taught for over 26 years in multiple countries and has spent a fair amount of time writing curriculum. Welcome, Jennifer.

Jennifer Brandsberg: Thanks for having me, Mason.

Mason Pashia: You bet. Um, I really enjoyed digging into some new curriculum you’ve been creating around regenerative economics, which we’ll get into here in a second, but as I was in there, I was struck by the fact that you have a poem included. For those of you that know Getting Smart and me, you know that I talk about poems too much. Fortunately, this is a short poem. So, I’m going to read it really quickly. It is called “Naming the River” from Field Guide to the Haunted Forest by Jared K. Anderson.

The water in your body is just visiting. It was the thunderstorm a week ago. It will be the ocean soon enough. Most of your cells come and go like morning dew. We are more weathered in pattern than stone monument. Sunlight on mist, summer lightning. Your choices outweigh your substance.

Why include this in your curriculum, Jennifer?

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah, it might seem odd to include a poem in an economics textbook, but we’ve taken a number of unusual steps like this throughout the work. For me, this poem was really important to share with students so that they could understand that they’re part of nature, not separate from it, which is something that our current economics courses teach them both explicitly and implicitly. And, uh, we included this at the start of a section on biogeochemical cycles. So again, it might seem odd that we would have a section on biogeochemical cycles in an economics textbook, but it goes with the big picture that we’re trying to help students understand that we’re connected with nature and we need to understand how nature works in order to redesign our economy so that they can be more regenerative.

Mason Pashia: You and I are going to do a little bit of a dance today, merging between international and national scopes as we talk about economics. In the States, economics is rarely discussed in classrooms, particularly in, I would say, well, all of them, but in high school, I think it really starts to make sense to talk about them. And even still, we don’t really talk about economics. People talk about things like we need more financial literacy in schools. We need some things that are like economic adjacent, but it still is lacking the scope and comprehensive view of systems thinking that economics naturally entails. Why is economics so important, and why should students learn it?

Jennifer Brandsberg: I mean, to understand why economics is so important, I think it’s really helpful to understand what the economy is and what the discipline of economics studies. So, the way we’ve defined economics, the economy in our book, is that it’s all the human-made systems that we use to transfer and transform energy and matter to meet human needs. And so, the discipline of economics is the study and practice of how to do this. In my mind, there just seems to be nothing more fundamental or critical to our lives on this planet than understanding how we organize ourselves to care for other human beings and the ecosystems on which we depend. So, I’ve taken, I guess, a much broader view of what economics is and what the economy is than you might find in some economics textbooks. And I would also add that, you know, if you’re looking at your economics course, if you’ve got one, and you’re teaching one, and you think, ah, this isn’t really essential, then you’re doing it wrong. And that’s what we’re trying to address here with this new curriculum.

Mason Pashia: So if you actually look at the word “economy” or “economics,” the literal translation to it in Greek is “management of the household,” which I think really sums up a lot of what you were just saying. It’s like how do we fundamentally, in the economy, care for things that make up home. And I think that what you’re doing is taking a broader lens of that and saying this isn’t just home as far as like the actual structures of buildings and houses, but this is like the planet. This is each other.

Introduction to Economics and Ecology

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah, it’s a planetary home. And I think it’s worth noting that ecology starts with the same root, right? So it makes total sense that if you’re studying economics, you also need to know how nature works.

Mason Pashia: Totally. And you have some experience teaching economics over the years. Is that correct?

Teaching Economics: Challenges and Realizations

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah, I’ve been teaching economics mainly in the International Baccalaureate since 2001. I was an examiner. I’ve written textbooks. Uh, yeah, so I have a lot of experience and background in the course.

Mason Pashia: So was this something that in 2001, if you were teaching an economics course, were you Trojan horsing like all of this regenerative thinking in, or were you kind of sticking to the original script? And this is something that was more of a revelation to you along the road. How did your shape thinking get shaped?

Rethinking Economics: Pluralist and Regenerative Approaches

Jennifer Brandsberg: This was not on my radar at all. I think, like most teachers, it was really something that I started to think a bit more carefully about around the time of the financial crisis. At that point, I had a brief pause in my teaching because of a move. And when I came back to it and took a closer look in the context of that crisis and all the talk and commentary around inequality, then I started realizing that there were some pretty significant problems with the courses that we’re teaching. But still, even then, I didn’t really know what to do about it. There was no resource out there to access. And I was stuck with a very dense syllabus and a high-stakes exam at the end. So it’s very, very difficult to go off script if you care about your students’ results. But I started reading a bit more widely in pluralist economics. And when I hit on Kate Raworth’s book Donut Economics, I read it in 2018 while I was on vacation with my family and I couldn’t sleep.

Mason Pashia: Great vacation read.

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah, it’s really fun. It’s actually a fun read about something that’s very, very serious. But for me, that book was paradigm-shifting. And that was in large part due to the way the book itself is structured and thinking about old economic thinking and seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. So, yeah, it was like candy. And from that point on, then I started to take the work that I was doing a bit more seriously in terms of trying to find ways of getting new economic thinking to my students. But even then, I mean, for years afterward, I was still stuck with the book, the old syllabus, so I had to find some creative ways of getting that thinking to kids. And, you know, for example, that took the form of having an afterschool group looking at alternative texts. It ran to running webinars on donor economics so that I could help other teachers see how they could bring in some of this thinking into their classes. And then ultimately, starting to work on textbook writing where then I was able to weave in some of this information into textbooks because even though it might not be in the syllabus, if you’ve got your hands on a textbook, you can also get some of this to students and the teachers.

Mason Pashia: So I think we’ve kind of scratched the surface of the framing of this curriculum and how it’s different. But can you give me a little more of an example of what’s different between traditional economics and this regenerative economic view?

Jennifer Brandsberg: What I’m about to say might not hold completely true for your economics course and your context, and I’m aware of that. Nonetheless, I think we can make some generalizations about some of the problems. One of the first things I would say is that economics courses focus almost exclusively on markets, and the courses tend to draw a relatively hard systems boundary around markets. And that systems boundary leads to some really interesting linguistic formulations. Like we constantly talk about the state intervening in markets as though somehow the state is not a natural part of our economy. We talk about nature and society as externalities because they are external to this hard boundary that we’ve drawn around markets. And, you know, that’s highly problematic because nature, society, the state, these are all dynamic interconnected parts of an economy, and it doesn’t make sense to exclude them from whatever system you’re talking about.

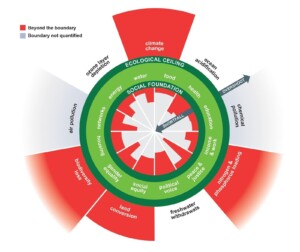

And markets—I’m not against markets. Markets are great. They’re powerful forces for allocating resources and products. They have huge, very powerful incentives built into them. But we can’t just focus on markets or largely on markets because there are other provisioning institutions that are also really important to the way our economy functions. The state is one of them, as I’ve just mentioned, but there are two provisioning institutions that are completely neglected by mainstream economics courses. One of them is the household. This is all the unpaid care and domestic work that happens in our economies, which some economists have estimated if you could put a number on it, would probably be the size of the global tech industry now, so it’s huge. And then secondly, the commons, which is all the self-organized work to manage shared resources that occurs outside the realm of markets and the state. In economics, we tend to talk about the commons as being tragic—that’s the only time you ever hear about it. But actually, there are many examples around the world of people who are able to successfully self-organize to manage resources. And Elinor Ostrom actually won a Nobel Prize for her research in this area. So I think it’s really important to understand that our economy is a really rich tapestry of human relationships. And we’re really not doing it justice by focusing so much attention on markets. Our course, this regenerative economics course, also has markets, but it’s just one of four provisioning institutions. And it’s put within the context of the, you know, it’s embedded—the entire economy is embedded inside society and inside natural systems.

Course Structure and Key Concepts

Mason Pashia: You’ve put out the first module or chapter of it currently, which is really like a broad overview of what’s coming, some really great places to get started. Then you get in different chapters and you just named a couple of them, but give us like the seven.

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah, sure. So we used the embedded economy model that you can find in Kate Raworth’s work in donut economics. So what we’ve done, first of all, is we’ve provided a topic. One is an introduction to the economy, and already in that topic one, there’s really a broad overview of what regenerative economics is, also a kind of explanation about how our current economies are degenerative. There’s a section on ecology in the economy, so quite a lot of information there to help students understand how we use energy and matter in the economy, the role, for example, of the huge pulse of energy that we receive from fossil fuels in the Industrial Revolution and what that’s done to the development of our economy, but also understanding how ecosystems work, biogeochemical cycles, and planetary boundaries. So there’s like a whole fat chunk in topic one about ecology and our economy, which is something you won’t see in any other economics. And it’s a really important part of this textbook, particularly for secondary schools. We also have a section on society in the economy as well that talks about human nature. It outlines human needs and the entire provisioning system. So how provisioning systems work, the donut economics model is in there. And very importantly, towards the end of that section is the role of care in the economy, which really is at the center, care for human beings and care for ecosystems. You’ve got that first topic, and it’s already—even just that one topic is, I think, enough to really move the needle quite significantly in economics courses. But after that first topic, what we do is we look at each of the four main provisioning systems: the household, markets, commons, and the state. Each one gets its own topic, so it’s quite different from a normal economics course that might just discuss markets and the state or micro and macroeconomics. And then after that, we’re looking at money and finance and international exchanges, but always through this regenerative lens, which is going to make the actual content of those topics quite different.

Mason Pashia: You have a list of guiding principles for this work. They’re lovely. I want to talk about maybe a couple of them. And I’ll just read through them real quick. It’s got: facilitate change from the ground up, cultivate local awareness and action, orient towards the sun, nurture interconnection, prioritize form that follows function, make space for emergence, and practice generosity. Great list of ways to live and words to live by. Out of these seven, which of these do you think is the easiest first step for someone to take? And then which of these do you think would take the most radical reimagining of the education system as we know it?

Jennifer Brandsberg: So I’ll just say these principles are principles that we used when we created these materials. So I don’t see them as necessarily principles, although I’m sure you could frame them that way, but I don’t see them as principles for someone else to follow when they’re teaching this. But I will just say it might be interesting for listeners to note who can’t see the course on their screen, but we’ve chosen a dandelion as the picture that graces the cover of the work. And that was really deliberate because we tried to think about a wildflower and a dandelion in particular when we created the materials. And so that’s where many of these ideas come from. The idea is, and what we’re trying to do, is to produce a set of materials that enable teachers around the world, even if you’re stuck with a mandated course that you hate, to bring in little pieces like seeds blowing from the dandelion that can settle in the cracks of your course where you see the possibilities and then grow into this wildflower and then spread even further. So that was one of the big ideas, the wildflower idea, and then provided the thinking around all the rest of the principles that we use. Facilitate change from the ground up, again, this idea of growing through the cracks. This is one of the theories of change or the approaches that we’re taking. First and foremost is to find those teachers around the world, and there are hundreds if not thousands of them around the world who are really clamoring for this work and give them something to work with. Because right now, if you realize there are problems with your course, there’s very little for you to grab onto to integrate into what you’re doing. We’re working on broader systems change as well. The grassroots work is really important, but we’re also working on trying to change curricula at a much higher level so that we can have a much more systems-wide impact. By creating such a comprehensive course, we’ve got a full syllabus. We’re creating a full set of what’s called in the UK a detailed specification. So all the learning objectives, details about the content, and the depths of learning we’re creating that as well. Plus, this two years’ worth of learning materials, online, open access, free, anybody can use it, adapt it how you like. The idea is that by creating such a comprehensive piece of work, it’s going to be much easier for departments of education, ministries of education, people who are working on broad systemic curriculum design and national curriculum and beyond to make a much bigger shift from their current syllabi when it comes time to do that revision work.

Mason Pashia: That’s great. Yeah. We do a lot of thinking about credentials in the education space, and I can see a lot of really wonderful credentials that stack alongside this curriculum as well. Getting Smart’s been thinking a lot about pathways over the last two years. So connecting students, primarily in high school, with what’s next in their career or life. So whether that be post-secondary or jobs or opportunities, how would you rethink a pathway structure? So connecting students to work through the lens of regenerative economics, like what are the things that are currently lacking in an apprenticeship model or something like that that would be informed by this kind of thinking?

Jennifer Brandsberg: What we’re trying to encourage teachers to do, to the extent that they can in their context, is to incorporate project-based learning, place-based learning, community engagement, change-making work, primary research, right? Really engaging with their community. And one of the things that I love about this course, in contrast to what we see in mainstream economics courses right now, is that we’re not just teaching students about the economy or about markets more narrowly. The course is really helping students understand their own lived experience, helping them understand and engage with their communities, to think about their role. They already have diverse roles in the economy, and I think that that kind of project and place-based work can really be an inroad towards the kinds of things that you’re talking about. Because you’re helping students understand this incredibly dynamic system in which they live, all the various ways that they can contribute to it, and developing agency. So I see that work like this, particularly if teachers are able to take up many of the extended projects that we have outlined in the work for teachers and students to help stimulate their ideas, this is completely complementary to what you’re talking about.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, it makes me think of the possibility of a social entrepreneurship capstone or something as well as a really hands-on way to take some of these learnings into potential work experience or skill building in that space.

Jennifer Brandsberg: I mean, you know, what came to mind instantly, and again, this is not necessarily paid work, but one of the projects that we’ve suggested in the care section is helping students understand the role of care in their economies is a project about developing a care walk in their community. So identifying all the places in their community where care work happens and then setting up a walk, a tour that they can bring other people on to showcase all of the care work that’s happening. It’s unbelievable the number of skills you can develop in trying to set up something like that in your community.

Mason Pashia: Making space for emergence and facilitating change from the ground up. So using those two design principles, I wonder if you could tell a little bit of a story about how this work got started. I know that you involved students. I know there were some very interesting movements. Could you just tell a succinct story about how this work got started and who was involved?

Global Movement and Future Directions

Jennifer Brandsberg: I’ve kind of had in the back of my head that I’d like to do something like this for a while. But I had a full-time teaching position and kids and life, so it was sort of difficult to make a big move on such a large piece of work. But last year, in 2023, I was approached by two student organizations, SOS UK and Teach the Future. SOS stands for Students Organizing for Sustainability, and they started a project called Track Changes where they asked academics and teachers to look at all the GCSE curricula. These are the school leaving certificates that happen just before the last two years of secondary school, so GCSE. They were keen to have people rewrite the national curriculum to include sustainability in every single subject. Many of your listeners might be aware that there is a big push for this across the world from many student organizations who just want to see sustainability embedded much more deeply across curricula in their schools. The project was called Track Changes because they put all the syllabi into a Microsoft Word document and put on track changes, and they asked these academics and teachers to make changes in track changes so the changes could be seen and also they could be accepted with the click of a button, which is part of their tagline. I was asked to work on economics, but economics is a little bit different from other subjects in that you can’t just make small changes to the curriculum to have it be fit for the 21st century. So, we decided that it would be great to do a much more substantial revision. I reached out to Kate Raworth of Donut Economics to ask her whether she would help. And she graciously agreed and pulled in some other academics, and we pulled in some other teachers. Together, we were able to make a much more substantial revision to that GCSE syllabus, and we called it regenerative economics. Interestingly, I would love to just call it economics, but we have to distinguish it from what’s happening in schools right now. So it’s called regenerative economics. The syllabus was published last May, May 2023. I was determined that this shouldn’t be just an academic exercise, so we started exploring how we could bring this work to life and create something that would enable teachers to get these ideas into their classrooms around the world and not just in the UK, but everywhere and in whatever context.

Mason Pashia: So if you’re an educator and you are looking at this curriculum and you’re like, “I agree with this, but I don’t know how I can get this actively embedded in the classroom. I either can’t map this to the standards in my district, or there’s somewhere someone somewhere that’s going to make this a little bit more difficult to do.” What advice would you give them, or what are some steps that they could take to start to incorporate this thinking with their students beyond some of the things that we’ve maybe already kind of touched on?

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah. So, first of all, I’ll just say we are trying to lower as many barriers as we possibly can. The work is free. It’s been funded. It’s open access. So we’re actually living the values that we’re talking about. The section on the commons, we’re putting this in the commons, which makes me really happy. Nonetheless, monetary cost is not the only barrier that is potentially going to get in the way of this being taken up. Teachers are pressed for time. If you are, for example, in the United States, an AP micro or macroeconomics teacher, you’re probably hard-pressed to finish the syllabus content before your students have to take the exam. That’s true around the world, whether we’re talking about the Indian CBSE or IB or the Australian national curriculum, etc. What I’ve been telling teachers is that there are no rules around this. And even if you only have time to do one lesson, that’s something. And if you let us know that you’re doing that, then we can count you in as part of Team Regenerative Economics because the goal of this project is about trying to get better information and learning to kids, but it’s part of broader social movements around reforming education generally on multiple layers, not just content but also pedagogy. It’s also about social tipping points as well. So if schools are starting to take up this work, then it also sends a message to businesses and to politics that we want shifts in thinking about the purpose of the economy and the role of care for humans and ecology in our economies. So, what I always say is, however little, however much, everything counts. And I’m also just really keen to help teachers. So if you have a syllabus you need to teach or standards that you need to adhere to and you want advice about what would be the most high-leverage pieces of this that you could try to incorporate in the most time-efficient way, I’m happy to help you think about that. I’m really excited about that. Good at that kind of thing, actually. I’ve been doing it for a long time. So, yeah, every little bit counts is my message.

Mason Pashia: Great. Yeah. We’ll be sure to include a way for them to get in touch with you in the show notes. To build on that a little bit, there’s a great section at the end of this first chapter called “Take Action” that has a handful of really great ideas to just start. It’s better scaffolded onto the curriculum, but I think a lot of them you could get a lot of benefit out of just by doing one of the activities that’s listed there. As I mentioned earlier, my one biomimicry self-directed study in eighth grade was formative in my life and had no curriculum associated with it. So I think these can have really long-lasting impacts. I wrote a blog about how it shaped my life for Getting Smart. I’ll put a link in the show notes. Two things that this is bringing to mind for me as well: examples in the States of people that are doing something on the fringes of this. Our listeners are very familiar with place-based education. We did a big campaign on that in 2017 called Power of Place and wrote a book on it. There’s an example of a school called Red Bridge in San Francisco in the United States. It’s a K-2 micro school, and they have a whole lesson on noticing every day. It’s just practice in the act of noticing, which really resonates with some of the stuff in your take action section around spending time indoors and really thinking about the ways in which systems are shaped or places are made. It’s an act of placemaking. It’s an act of recognizing relationships and dependencies and interdependencies. Additionally, there’s a great micro school called the School of Environmental Leadership (SEL), which is within a public school district and also in California. This is all about just—students go through their entire high school experience mapped onto environmental leadership. So everything that they’re doing is thinking about things through the lens of sustainability. They have an arc of policy work to advocacy to organizing all throughout their school day. All incredibly valuable and transferable skills that will take you far beyond the realm of just sustainability, which applies to everything but also can sometimes be niche-ified. So people are doing this all over, and there are a lot of really low-lift ways to get started, but this curriculum is a beautiful way to keep building and scaffolding it on for people and to help people deepen understanding and be able to go further. Jennifer, any closing thoughts on this? I will definitely keep sharing these as they come out and put them in the link, particularly to this podcast as the whole curriculum drops, so to speak. But this is really exciting work, and thank you for putting it together.

Jennifer Brandsberg: Yeah. Thank you. I guess just as a final word, I would just say please don’t hesitate to get in touch. You’re not bothering me. And I’m really keen to know how you might be able to use it and to support you as you’re using it. This is really gaining a lot of momentum, which is very exciting for me. And yeah, I really see it as a global movement to get better economics for our students and help us understand how we can—our economies have been designed. Kate Raworth says this all the time, right? We designed our economies; we can redesign them. Same for the curriculum, right? It’s not been handed down by God. We made it. If it’s not working anymore, let’s fix it. And we can all play a role in that. So, yeah. And spread the word, please.

Mason Pashia: Um, and Adrienne Maree Brown, great author, also says we live in somebody’s imagined future, so we have to imagine a different one. So I think very similar sentiments around that theme. Thank you so much for being here. If anybody does try any of these, be sure to share with Jennifer or Getting Smart. We’d love to share your stories about how this is working. And thank you for listening to the Getting Smart Podcast.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.