Growth Mindset Parenting

Eduardo Briceño

Many of us want our children to understand that we love them, and to believe that life can be fulfilling. Developing those beliefs will help them prosper. There is another powerful, research-based belief that will help children thrive. It is called a growth mindset.

What is a growth mindset?

Discovered by Stanford Professor Carol Dweck, Ph.D., a growth mindset is the belief that we can develop our abilities, including our intelligence, which is our ability to think. It is distinguished from a fixed mindset, which is the belief that abilities can’t change, such as thinking that some people can’t improve in math, creativity, writing, relationship-building, leadership, sports, and the like.

The mindset that we adopt leads to very different behaviors, improvement, and achievement. For example, research on adults shows that people who believe that good negotiators are made rather than born –a growth mindset about negotiation skills– persevere in tough negotiations, create more collective value, and capture more of the value in negotiations, as compared to those with a fixed mindset. Similarly, people who believe that leadership skills are developed –a growth mindset about leadership skills– feel inspired rather than threatened by other leaders, have higher confidence in their own ability to lead, and experience lower anxiety and higher performance in leadership activities. Managers who believe that personal qualities can change seek and welcome feedback more, notice changes in employee performance more accurately, and take on more coaching-oriented behaviors, leading to improved team capability and performance. And lots of research has shown that children with a growth mindset seek more effective learning strategies, work harder, persevere in the face of setbacks, and achieve higher competence.

Why does this happen?

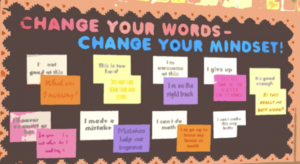

It turns out that a fixed mindset, which is seeing abilities as fixed, leads people to see effort as a sign of inability and to feel badly about themselves when needing to expend effort, so they avoid it. But those with a growth mindset see effort as what makes us smart and capable, so they seek it. Second, people with a fixed mindset are most concerned with being judged by others as smart and talented, so they gravitate toward doing things they already know how to do quickly and perfectly. But those with a growth mindset can get bored when they’re doing something they already know how to do, instead preferring to challenge themselves to learn something new, which is necessary for growth and improvement. And when they encounter setbacks or failure, people with a fixed mindset tend to conclude they’re incapable, so to protect their ego, they lose interest and withdraw, while those with a growth mindset understand that learning something new involves struggling and making mistakes, so they persevere. If you’re interested in learning more, here are more articles and videos on the growth mindset.

How can we develop a growth mindset in our children?

Children learn whether abilities are fixed or malleable from their observations of the world. If we, adults, have a fixed mindset, we will behave and communicate in fixed-minded ways –such as shying away from challenges or talking about people as if their abilities are fixed. This will tend to encourage a fixed mindset in our children. For example, when we think that people are either smart or not, we may find ourselves praising our children for being smart, rather than for the effort or strategies that led them to success. We do that with our best intentions, in order to raise their confidence and self-esteem. But research shows that when we praise children for being smart, they adopt a fixed mindset (i.e. thinking that people are either smart or not), and as a result when things get hard for them they conclude that they are not smart and they experience higher anxiety, lower confidence, and lower performance. They also become less interested in learning, and more interested in showing what they already know how to do. While being told they’re smart may make them feel good in the short term, the deeper lesson they learn is that people are either smart or not, and when things get hard, they feel incapable.

We’ll be more successful in developing a growth mindset in our children if we also work to develop it in ourselves, which is never too late to do. How can we do so?

Learn about the malleability of abilities and how to develop them. Explore whether abilities are really fixed or malleable, and how expertise is developed. Great books on this topic are Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck, Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin and The Talent Code by Daniel Coyle.

Monitor your self-talk. Pay attention to your own internal dialogue about abilities. When you see a highly capable person, do you recognize the hard work it took to develop that competence? When you or your child struggle to do something, do you tend to conclude that you can’t develop the needed ability, or that you haven’t developed it yet? When your child does something well, do you praise them for being talented or help them reflect on the behaviors that led them to success?

When you realize you’re thinking in a fixed minded way, observe what effect that thinking has on you, and remind yourself of what you’ve learned about the malleability of abilities and what it takes to develop expertise.

Become a role model learner. Children observe and imitate us. If we want them to be interested in learning and work hard to develop their abilities, we need to do the same ourselves. Setting learning goals, working hard to improve, and making our learning process visible to those around us are ways to demonstrate that effective effort is worth doing and leads to improved abilities. Talk about the challenges you are taking on, the mistakes you’re making, the lessons you’re learning, and your progress.

Be deliberate about the messages you send. When we feel uncomfortable calculating the tip on a restaurant bill and hand it off for someone else to calculate, it conveys that we think we can’t learn math and don’t work to develop our abilities. When we speak about other people as smart or naturally talented, or unfit for a particular area, it conveys that we have fixed mindsets, which prompts children to do the same. When we cover up our failures or mistakes, rather than reflect on and discuss them, it conveys that mistakes are a sign of inability, rather than a consequence of challenge and an opportunity to learn.

Some people enjoy ongoing learning and growth as a source of fulfillment throughout their lives, one that nobody can take away from them. I wish that for you and for your children. Happy learning!

This blog is part of our Smart Parents Series in partnership with the Nellie Mae Education Foundation. We would love to have your voice in the Smart Parents conversations. To contribute a blog, ask a question, or for more information, email Bonnie Lathram with the subject “Smart Parents.” For more information about the project see Parents, Tell Your Story: How You Empower Student Learning as well as other blogs:

- Parents as Chief Advocates

- Early Childhood Learning is Critical for Our Own Kids’ Future…and the Nation’s

- The Power of Personal Relationship in Personalized Learning

Eduardo Briceño is the Co-Founder & CEO of Mindset Works, which he started with Carol Dweck Ph.D. and Lisa Blackwell Ph.D. and now serves hundreds of schools and tens of thousands of teachers and students to help them cultivate growth mindsets and effective learning strategies and habits. Learn more at www.mindsetworks.com and by following @brainology.

Eduardo Briceño is the Co-Founder & CEO of Mindset Works, which he started with Carol Dweck Ph.D. and Lisa Blackwell Ph.D. and now serves hundreds of schools and tens of thousands of teachers and students to help them cultivate growth mindsets and effective learning strategies and habits. Learn more at www.mindsetworks.com and by following @brainology.

Syoung

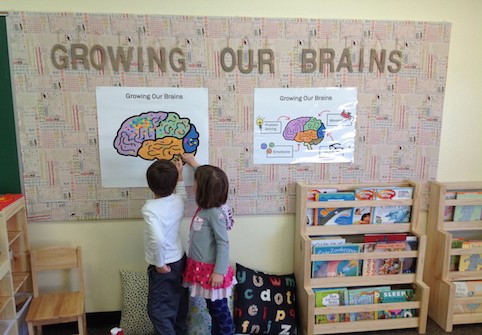

So important!! Would love to know where the posters in the photo, particularly the on one the right, came from. Thanks!