The Do-It-Yourself Movement Goes to School

By: Patricia Gomes

The Do-It-Yourself Movement Goes to School first appeared on Porvir on November 11, 2013.

Rodrigo Benoliel, 13, thinks that he wants to be an engineer. If so, when he takes the college entrance exam four years from now, or enters the job market in nearly a decade, his portfolio will already be full: robots, models, circuits, and even an award-winning model of a sustainable home, with systems to reuse water and solar panels. His friend, Mário Grünbaum, 14, shares the experience with inventions large and small, and also some doubts: he thinks he might major in Engineering, if he doesn’t study Medicine. The boys have been taking classes and workshops on robotics since last year at their school, Liessin, in Rio de Janeiro.

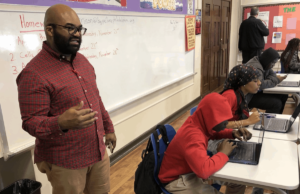

Wednesday there is sacred; it’s lab day. Benches equipped with drills, lathes, cutting tools, automated Lego parts, and soon a 3D printer, have produced swimming goggles with performance data for athletes, low-cost electronic canes for the blind, and all kinds of products that the students have decided to create according to their own interests. The man in charge of this paraphernalia – in the good sense, of course – is Charles Lima, a true Gyro Gearloose, who studied computer science and was in charge of the computer lab until he realized that the future was no longer there. “The school turned into a breeding ground for ideas,” he says. He has seen the effects of the experimentation go well beyond the laboratory.

Every movement to innovate in education has a honeymoon phase, when everyone wants to do it. That is exactly where the Maker Movement is. Everyone wants to set up a fab lab, but this could also fade away two years from now if we don’t produce results. That’s why my focus as a researcher is to show the results of this. Labs like Lima’s and his robotics classes are popping up all over Brazil. To get an idea of how this has exploded, at the Brazilian Robotic Olympics (OBR), which involves students from throughout the country, the number of people registered went from 5,000 the first year in 2007, to nearly 50,000 this year. These figures are an indication of what is known as the “Maker Movement” or “Do-It-Yourself”, which is well-established in the United States and Europe and is starting to break into Brazilian education. Worldwide, the movement is organized around laboratories in universities, in public or private places called fab labs, or digital fabrication laboratories.

Fans of programming-engineering-design are able to create prototypes of their ideas in these spaces, which are equipped with tools that technology has helped make affordable recently. They may be students, researchers, entrepreneurs who want to develop the first versions of their product, or even just for fun. For the job of creating things and seeing them work. Besides the actual labs, the market promotes a series of events to attend, called Maker Fairs, and an array of specific publications, including the magazineMake, which helped give rise to the movement.

The fab-lab network has over 200 laboratories worldwide that share information with one another. In Brazil, there are two, both in São Paulo – one connected to the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at USP and the other in a makeshift garage downtown. Next year at least one more is scheduled to open in Recife, and in educational environments, one at Insper (a university known for its Business and Economic programs), and another at a school in Rio de Janeiro.

“We are a very horizontal network. Despite the movement having been created at MIT, it only asks us to follow a charter of principles, the Fab Charter. It’s a conceptual charter that sets out the network’s concept, but not a strict model to be followed. That is why each of the fab labs has very specific characteristics connected to its location and the people who work there. We have different fab-lab models as well: those aimed more at education; professional ones; and those that function as a public structure in cities,” explains Heloisa Neves, executive director of the Associação Fablab Brasil.

Impact on Learning

In the U.S., a Brazilian has been in charge of the Fablab@School project since 2008. A professor in the School of Education at Stanford University, Paulo Blikstein, an engineer, has set up fab labs in schools around the world: Russia, Thailand, Mexico, Denmark and the U.S. In general, these spaces have a 3D printer, a laser cutter, robotics equipment, and they are used by professors in all disciplines to develop projects. In each of these fab labs, Blikstein gathers data and tries to generate scientific knowledge about what this style of learning can offer. “Every movement to innovate in education has a honeymoon phase, when everyone wants to do it. That is exactly where the Maker Movement is. Everyone wants to set up a fab lab, but this could also fade away two years from now if we don’t produce results. That’s why my focus as a researcher is to show the results of this,” he says.

And the results are clear, he adds: more motivated students with better self-esteem, able to work in groups and solve problems, capable of communicating well with one another. “Children need an alternative front door to the one normally offered by the school, which is to sit in a classroom and listen to a teacher. If you offer that, like the opportunity to create projects, robots, devices, you get children to come to school and afterward they even attend class in a very different way. But they’re already in, already interested in staying in school, already interested in doing their projects better,” Blikstein claims.

The poise of boys like Rodrigo and Mario when describing their feats in the lab is proof that confidence and ownership are characteristics that robotics projects help to develop. “Since I’m good at hands-on activities, I normally end up with the construction part. As a builder, I like to see what I created work perfectly. If I put a part in the wrong place, it doesn’t work,” Rodrigo explains about the part of the process that brings him the most satisfaction. “I like to go to the lab because I do a lot of things there. The work of assembling a robot requires programming, attention. When I finish, it isn’t likely that someone else will have created one like it. I’m able to express myself through my robot,” Mario adds.

According to Blikstein, setting up fab labs has gotten less expensive thanks to cheaper equipment. A 3D printer, which only large corporations and top universities could afford, now costs US$1500, the same as a laptop. Brazilian manufacturer Metamáquina is developing a printer here that will cost R$ 3900. In the US, MakerBot announced a crowdfunding initiative this week to get one of these devices in every American school.

The toughest part, therefore, isn’t access to equipment, but training teachers for this new uncertain reality of sharing experiences, Blikstein believes. “Teachers need to be familiar with the equipment, to be open to children’s ideas to help with diverging projects. The charm is in the difference,” he states. He is leading a call for teachers to sign up for a program to share experiences. Heloísa agrees: “In this [new configuration] the teacher’s role is even more important, because she has to teach the student to look for information in the right place to have the critical capacity to triangulate information in order to decide on a path.”

The direct consequence of this more independent pursuit of knowledge is that information no longer fits into neat little boxes in the school’s classes or even in colleges. Thus, to develop an automated flute, for instance, students are going to use knowledge of mathematics, programming, music and history. In college, even barriers between very different programs can theoretically fall. Vinícius Liks, who was responsible for bringing the fab lab to Insper, says that the common experimentation space will be useful to students in all types of majors, because it makes them take a different look at life, more related to design.

“They will have to look at a problem from different angles. Economists and engineers have a habit of finding an optimal solution to a problem. But in real life it isn’t like that. If the context changes a bit, then the solution is no longer optimal,” Liks says. Gilson Domingues, who teaches design and workshops to set up 3D printers, also believes that “affectionate learning” and concern about coming up with answers to challenges even makes better citizens. “Students start dealing with problems from the perspective of someone who can do something; of someone who is no longer just a consumer,” he says.

The ‘maker’ attitude Thus, digital fabrication labs shorten the project-development process, allowing their users to create a prototype, make a mistake, fix it, and experiment, creating rich learning opportunities. But they don’t do magic. “I’m tired of visiting beautiful labs where students keep brining technicians a pen drive with their file, and the technician makes exactly what the student wants. In other words, the division between theory and practice, or between those who think and those who create, still exists. This has nothing to do with our world,” Heloísa states.

According to the director of the Associação Fablab Brasil, “do-it-yourself” or “DIY” turns students into technology producers, rather than just consumers. “Students ought to understand how to work with machinery, with the ‘code’, with electronics. Then they can go beyond that and make the equipment work the way that they want it to work. Labs need to let students get their hands on the machines and break down from time to time. A fab lab without the maker attitude isn’t a fab lab,” Heloísa concludes.

Please see the infographic below which explains the maker movement.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.