Voices of Small Schools Podcast: Accessibility

Key Points

-

School founders take proactive steps such as sliding tuition scales and intentional locations to support learning for young people through various learning environments.

Join Digital Promise and Verizon Innovative Learning on Thursday, November 14, for the third annual Elevating Innovation Virtual Conference. Register for free at digitalpromise.org/elevatinginnovation.

In this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, hosts Jordan Luster and Victoria Andrews dive into the world of microschools, exploring how these small, adaptive learning environments are making education more accessible and equitable. The conversation touches on the different strategies employed by microschool leaders across the country, emphasizing their commitment to overcoming challenges like financial barriers and geographic limitations. Through real-world examples, listeners gain insight into how microschools are expanding their reach through unique funding models, education savings accounts, and community partnerships that ensure inclusivity for all students, regardless of their background.

The episode also delves into the personal stories of microschool founders, revealing the passion and dedication driving these educational pioneers to create impactful change. By prioritizing equity and accessibility, microschools are not only addressing the immediate needs of underserved communities but also setting a precedent for broader educational reform. The podcast underscores the importance of innovative leadership and strategic collaboration in fostering environments where all learners can thrive. As the hosts and guests discuss the future of microschools, they paint a vivid picture of a more inclusive and adaptable education system, one that is poised to significantly narrow the equity gap and empower students to become active contributors to their communities.

Outline

- (00:00) Exploring Microschools and Their Impact

- (02:56) Challenges and Opportunities in Microschools

- (05:41) Real Stories from Microschool Leaders

- (16:42) Future of Microschools and Accessibility

Exploring Microschools and Their Impact

Jordan Luster: You’re listening to the Getting Smart podcast. I’m Jordan Luster, and today, I am joined by Victoria Andrews.

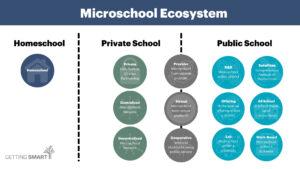

Jordan Luster: We’re going to be guiding you guys through a conversation as we hear from several school leaders and share our own thoughts on the ways that these innovative microschools are becoming more accessible. Together we’ll unpack the challenges and opportunities that come with making microschools available to all students. Now, over the past couple of years, we’ve been talking a lot about how microschools can lead to macro change. We’ve shared about how they create new options for families, how they can be used to quickly address underserved populations, and how they’re really a catalyst or vehicle in starting innovative practices.

Now, since then, at Getting Smart, we’ve focused a lot of our efforts on supporting microschools, with an emphasis on high-quality innovation that serves historically marginalized and underserved communities. We acknowledge and understand that the creation of microschools can lead to inequities, and we’ve kept that at the forefront of all of our efforts, including the facilitation of community of practice strands.

Victoria is leading, providing coaching and technical assistance for microschool leaders, and most notably, our funding efforts. Last year, we launched our Learning Innovation Fund, partnered with the Walton Family Foundation, and introduced the Big Push for Small Schools Grant program. Our mission was really to foster a network of microschool leaders by offering grants to propel the development of their innovative learning spaces, focusing on supporting operators looking to scale their high-quality models.

And so, in this work, we’ve learned a lot about the sector and the landscape. Throughout all of our learnings, we’ve been able to identify some key themes around sustainability, scalability, and accessibility.

Challenges and Opportunities in Microschools

Jordan Luster: Today, we are taking on the accessibility of microschools.

Now, one of the biggest critiques that we have heard around microschools is this concern that they are exclusive—the exclusivity and the risk of privatizing education, making it less accessible to the broader range of learners out there. But what if we reframe our thinking, right? Like, instead of seeing these schools as exclusive, we start looking at them and viewing students as curators of their own learning experiences.

One of the goals of this conversation is going to be to highlight how microschools can and should be accessible to all learners, regardless of their background, location, or resources. We’ll explore some questions around accessibility, like: how can we make microschools financially accessible—whether through tuition-free models or public funding like ESAs (education savings accounts)? We really want to dig deep and understand what it means for a microschool to be accessible to all.

And how can we expand public and private partnerships that blur the lines between traditional and alternative education models? I think that, most importantly, we really want to discuss how we can ensure that microschools are available to all students in rural or underserved communities. We’ll touch on some of the challenges of sustaining these models, especially for school leaders with small teams and big visions.

The question remains: how do we ensure microschools can serve all students, including those with learning differences or special needs, in both public and private settings? So, you ready to dig in, Victoria?

Victoria Andrews: I am. I’m so excited because, historically speaking, microschools—the one-room schoolhouse concept—have been around forever. And if you think about even the origin stories of that, like Freedom Schools and Sabbath Schools, those schools were created out of need and for targeted populations, whether it was young Jewish learners or, in some cases, formerly enslaved young people. Those schools needed to be created and accessible.

You had students in multiple grade levels, of multiple age ranges, being served by either a community or a group of people. So I’m very excited for this conversation and ready to hear from the different school leaders.

Real Stories from Microschool Leaders

Jordan Luster: We spoke with Tiffany Blassingame, out of Atlanta, earlier this year about how she ensures the accessibility of her microschool model. Let’s hear what she had to say.

Tiffany Blassingame: Yeah, so what we share with our families and with our community, in general, is that we want to make sure that every child, no matter their background, ability, or zip code, has access to equitable education. Kids can come as early as 8:30. Many of our kids drive or ride over an hour to get to school each day—not just at the Ferguson school, but at the other microschool I described. We’re centrally located in metro Atlanta, so kids can come from different spaces. They arrive at 8:30 and leave at 3:00. We would love to be able to provide transportation at some point, but out of 19 students, we’re pulling from 14 different zip codes.

So we work to ensure our location is accessible and our hours work with parents. There’s an aftercare program that the church provides, which our students can attend until 6:00 PM. Running that program isn’t on us, but it’s made possible through a partnership with the church, which ensures our kids are able to attend. That’s one big part of it. Also, accessibility as it relates to tuition is important. Tuition is based on what it takes to run the program, and about 70 percent of our families would qualify for free and reduced lunch, so they can’t always pay full tuition. We have an adjusted tuition rate model where it’s essentially a “pay what you can” model, and families commit to paying that for the entire school year. We then look for corporate sponsors, small businesses, and individual donors to make up the difference in those families’ tuition. This support is huge in making our program accessible while allowing us to provide quality instruction, curricula, and teachers.

Victoria Andrews: What I appreciate about what Tiffany shared is how she utilizes location when she thinks about accessibility. She decided to capitalize on the location of a place of worship in metro Atlanta. And if you’ve ever had the delight and joy of driving in Atlanta during the morning or afternoon, you’ll know that it can be quite a challenge. For her to factor that in when choosing her microschool location, as well as the times they accept young learners and capitalizing on the after-school program offered by the place of worship, is all about meeting the needs of working parents. Most parents have to work, so knowing that she, in collaboration with the church, offers after-school support for parents is just great. I also love her sliding-scale tuition model, which opens doors. While Georgia has just opened its ESA program, her model has been in existence for a few years, so she’s now just beginning to benefit from those funds.

Jordan Luster: I think that takes looking at accessibility through the lens of a parent, like considering the challenges parents and families face in ensuring their children can get to school. I like that she offers early care with a later start time, especially since that’s not common in Atlanta. Her responsive tuition model, where families pay what they can, is essential in making sure accessibility is prioritized. And next year, when we see those vouchers fully available in 2025, I’m excited to see how funds will support schools like hers. Another school in Atlanta, another microschool in Atlanta, we spoke with the school leader April Jackson, school leader of The Past Pod. And I’d love to kind of listen in on her thoughts about keeping her model accessible, especially being in the same city. Let’s take a listen.

April Jackson: One of the things that we do is try to keep the rates affordable. To run a microschool in Atlanta, it takes $8,000 to $12,000 per year. So one of the things that I do right now is supplement my income and the revenue for the business by working another job to keep tuition low. The community I serve has a high poverty rate, with an average income of about $30,000 per year. Parents really can’t afford it, so we keep the tuition low. Another approach is making the age range wide, which allows a parent with children of different ages to bring both to one place.

Another thing I’ve done to make it accessible is creating a second microschool within mine. I prefer to serve children ages 8 to 13, so I partnered with another microschool, Spectacular Start, which serves children from kindergarten to second grade (ages 5 to 7). This way, parents have a place where children in elementary and middle school can attend in one location.

Jordan Luster: Now, the thing that I truly appreciate about The Past Pod is that April Jackson is also running microschools in Atlanta. She does a good job of partnering with other microschools, which we saw heavily in the previous model with Tiffany, at the Ferguson School—that model is more in-house, with three schools in one. The Past Pod is very intentional about working with microschools across the city. And if you’ve been to Atlanta, it’s pretty big. When we talk about Atlanta, we’re really talking about Metro Atlanta, the city and surrounding areas. This is a middle school, and partnering with a microschool that serves elementary-age students allows families more choice. If you have middle school-aged children and elementary-aged children, it’s essential that both have an option for school. She’s created her own loose network of schools to make the model accessible not just for her students but for their siblings as well. I love that.

We also see how she’s created a sliding scale for tuition, which is a recurring theme across tuition-based microschools in Atlanta. Many schools strive to meet community needs, providing scholarships and partnering with organizations for subsidies. And I’m really looking forward to what Atlanta will do with these education savings accounts because I think that will be the true difference we see—the buffer that families truly need.

Victoria Andrews: You know, Georgia joins about 15 to 17 other states that already have ESAs. It’s going to be interesting to see the rollout, to see how they adjust, pivot, and respond to caregivers and parents as they navigate a new system that allows for greater accessibility for their young learners, whether they’re elementary-aged or middle school students just now getting into extracurricular activities and sports. Now they have the option of being on travel teams, and if they can access online classes, it opens up a whole new world for caregivers and parents.

Jordan Luster: Let’s listen to Heather DeNino about her microschool model in Massachusetts. They currently don’t have education savings accounts, so I’m interested in hearing how she’s made her model accessible to all learners.

Heather DeNino: This is a huge focus of ours, and it’s something that we continue to struggle with because we have to pay our teachers a living wage. The overhead of running a school is very high, but it’s our biggest commitment to make it accessible to families who need it, regardless of what they can pay. Here, we have what’s called a CARMA Scholarship. We’re always looking for donations to that CARMA Scholarship so we can keep equity pricing on a sliding scale and offer scholarships to those who need it, particularly for the BIPOC community and the LGBTQIA+ community.

Jordan Luster: Now, one thing is for sure—I completely understand that tension between keeping your school accessible and trying to ensure your teachers are paid a fair living wage. It’s an ongoing challenge for so many schools, especially those deeply committed to equity. And I’ve seen that microschool leaders do a great job providing alternative benefits to their teachers, but it’s a struggle to maintain top-quality talent and certified teachers. That’s some of the pushback that microschools and other alternative schooling models, like charter schools, receive regarding teacher certification.

But one thing we’ve seen is that teacher certification doesn’t always equate to the expertise and knowledge they bring. Microschool leaders are incredibly intentional about how they train, recruit, and retain their teachers. It’s interesting that Heather touched on this, because you can’t talk about accessibility for families without making sure teachers are supported fairly.

Victoria Andrews: Exactly. We could have a whole other podcast on accessibility regarding teacher pathways because all the different paths to becoming a teacher are interesting. Knowing that Heather’s campus is targeted towards the BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ communities, it’s vital that her teachers are equipped not only with skills but with competencies in how to navigate and ensure they’re meeting the needs of those families and young learners.

I’m excited to hear next from Amar Kumar with KaiPod and how they are tackling accessibility. Kaipod is a network with locations across multiple sites, so let’s hear what Amar and the KaiPod team are doing to make sure they create small learning environments that are accessible as well.

Amar Kumar: This is super important to us, and we have three strategies. First is setting tuition at a point where we’re essentially making ends meet. We’re not overspending on things, like renting locations that are too expensive, because all of those factors impact affordability for families. Number one is managing our expenses. Number two is scholarships. We have a buffer in every tuition payment for scholarships, so we’re able to lower tuition for some students by capturing higher tuition from other students. That helps us in a cross-subsidy model. And then third, most of our microschools are in states with some form of public funding.

Future of Microschools and Accessibility

Jordan Luster: Now, the scholarship model, where higher tuition helps support students who need financial aid, is a great example of how microschools can prioritize equity in a way that other schools may not because of their size. That cross-subsidy approach is crucial in ensuring that no student is left out due to financial barriers. I really like that Kaipod has created a way to keep that buffer in place, as Amar said, to support students who may need it.

Victoria Andrews: It takes a community-based approach and mindset, which is foundational to accessibility. Historically, microschools and small learning environments were born out of community need and shared decision-making. Kipod’s model is a modern take on that approach, supporting learning and education for everyone. It’s not about one student paying more and getting more; it’s about making education a community investment so every child benefits.

Jordan Luster: Yes, and I think that highlights how community-centered most microschools operate. They strive to meet community needs and leverage the community’s strengths to support their model. Kipod stands apart from the other schools we heard about because they are leveraging public funding programs like ESAs, tax credits, and vouchers, which makes microschools accessible to lower-income families and opens doors for a wider range of participation.

Now, while ESAs don’t necessarily guarantee accessibility, they can offset costs in a way that makes the model more accessible. Traditional private school tuition is often high, but what we’ve seen with microschools is that their tuition, being intentionally designed with accessibility in mind, is usually lower. Research shows that vouchers and ESAs typically don’t cover full private school tuition—there’s usually a gap of 20-30 percent that families still have to cover. And not all families have that additional money on hand. But with microschools that utilize scaled tuition models and offer lower base tuition, ESAs can be transformative.

I want us to hear from Joe Connor, the CEO and founder of Odyssey, a technology company that acts as an ESA wallet. Odyssey helps families utilize and access education savings accounts, so let’s take a minute to hear about how they are helping facilitate this process and making microschools more accessible.

Joe Connor: One of the things we focus on is making it super simple and easy for parents to sign up. It was the largest-ever launch for an ESA, with over 30,000 applications, 19,000 approved students, and about 17,000 who enrolled. The initial year saw a lot of existing schools backfilling enrollments—like Catholic schools that had been seeing enrollment decline for decades. So, it was great to see these schools filled to capacity. But what’s happening now might be even more exciting. In year two, we’re already seeing a lot of entrepreneurial activity, especially in the microschool space.

Iowa is a large state with many rural areas, and while we had high per capita participation from rural towns, there weren’t always many choices. A cool thing in year two is that we’re seeing teachers and principals leaving existing schools to start new schools. We’re also seeing more public school educators starting microschools, which this program enables them to do. This year alone, we’re seeing a 10 percent rise in the number of private and microschools in Iowa. It speaks to how much demand there is and how the ESA catalyzed supply by increasing the availability of microschools.

We’re excited about two things: continuing to increase our services in existing states, making sure we better serve microschools and parents, and expanding our platform.

Jordan Luster: It’s truly incredible to see how Odyssey is simplifying the ESA process and making it easier for families to access these opportunities. The real-time identity verification system is a game-changer. I’ve heard from families in Florida who talk about the complexities and wait times, so Odyssey’s system helps families overcome these barriers. Real-time approval in seconds is impressive.

Victoria Andrews: When we talk about accessibility, we often forget about the parents and caregivers. If the system they have to navigate is filled with education jargon and procedural hurdles, it becomes overwhelming. Accessible options should be as easy for parents and caregivers to access as they are for students to benefit from. I appreciate how Joe and his team are streamlining the process, because we can have all the equitable solutions in the world, but if they’re hard to access, then they’re not truly accessible.

So, speaking of unique and creative learning environments, I’m very excited to hear now from Andrew Lee, co-founder of Vita School of Innovation out of Arizona, and what he and his team are doing to meet the needs of high school learners. Many of the microschools we’ve looked at focus on elementary or middle school students, but Andrew and his team have a great learning space for high school students.

Andrew Lee: My teaching experience is rooted in Teach for America, which I love. Transitioning from engineering to education, Teach for America was the perfect pathway, and I appreciate their mission and vision, especially the commitment to every kid. With that philosophy in mind, we’ve designed our model to be free for every family. It’s helpful that we’re in Arizona, where we have a strong ESA program. We also have a partnership with EdKey and Sequoia Choice for an accredited partner program, which has been great, especially since we’re only in our third year and already tackling high school education.

Our focus is to eliminate unnecessary expenses typical of regular school budgets, like administrative costs. I’ve taken a modest teacher salary to make this work, ensuring our teachers are paid more than average while not driving up costs unnecessarily for families. I made this personal sacrifice so that accessibility is available for all families. For our teachers, absolutely—because that’s what it’s about. As a former teacher, I understand the hard work, and these educators deserve fair compensation. Fairness comes from careful planning, intentional budgeting, and, with EdKey as a partner, we receive around $7,000 per student.

Most of our students attend in person, but we also have an online program for those further away. This hybrid approach provides flexibility without students having to sit in front of a computer for eight hours. Instead, we do three check-ins a day instead, we do three check-ins during the day to help students create an action plan, provide accountability, and offer tutoring support. Our students who have tried other online programs appreciate ours because it strikes the right balance between flexibility and structured support.

Victoria Andrews: Andrew is such a lively guy, and you can feel his passion when you talk to him. I was honestly taken aback when he mentioned that, as a founder, he chose to take a teacher’s salary to avoid burdening the budget with administrative costs. Speaking as a former administrator, that perspective definitely challenges the traditional model of school budgeting. But when he explained how this sacrifice allowed all his teachers to receive fair compensation, I understood his logic.

His choice makes a real difference for accessibility by freeing up resources to support students. And his focus on high school students, who often contribute to their family’s income, is incredibly thoughtful. His four-day work week and flexible online options accommodate students who need to work 20-30 hours a week to help support their families. His team’s approach ensures these students can access college credits, prepare for college entrance exams, and excel academically, all while balancing life responsibilities. I think they’re doing something truly unique.

Jordan Luster: Hearing about Andrew’s budgeting approach—taking an intentional look at what’s within their control beyond tuition costs—really reflects his commitment to equity and accessibility. As a Teach for America alum, Andrew approaches education with an equity-driven mindset, always considering what’s best for families.

Microschools like his are often led by passionate leaders who prioritize community impact over profit. Even though microschools may serve only a small number of students, the impact on those students is profound. And that’s why I appreciate our focus on supporting microschools that aim to scale. For these models to be truly accessible, we need more of them, and I’m so proud to be part of this work, supporting these innovative models that are thinking deeply about accessibility, sustainability, and equity for the communities they serve.

Victoria Andrews: I couldn’t agree more, Jordan, and I’m glad I get to work on this with you. It adds a whole new level of joy to the work we’re doing. It’s truly inspiring to see microschool founders taking such a proactive, intentional approach to creating learning environments that are accessible, not only for students but also for the caregivers and parents who sometimes navigate challenging systems like ESAs or scholarship programs to provide the best learning options for their children.

To our listeners, thank you for joining us in exploring the challenges, opportunities, and innovations shaping microschools. If you’re interested in learning more about these schools or any of our other grantees, please visit GettingSmart.com/microschools. There, you can dig in and see how these unique learning environments are making a difference in the lives of young people and their families.

Amar Kumar

Amar Kumar is the founder and CEO of KaiPod Learning and has been working to improve education for students around the world for over 15 years. In addition to having been a teacher, a school principal, and a consultant in McKinsey’s Education practice, Amar was the Chief Product Officer for Pearson Online & Blended Learning for seven years. In that role, Amar designed and built the technology and curriculum that served more than 400,000 students in Connections Academy schools and school districts around the country. During the pandemic and through KaiPod Learning, Amar transitioned into an education entrepreneur, creating a new learning environment to support families that are seeking individualized and flexible learning options through online learning and homeschooling. Amar earned a Bachelor of Science in computer science from Purdue University and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

Tiffany Blassingame

Tiffany Blassingame is the Founding Head of School at The Ferguson School. She has been an educator for over 20 years and has a passion for early childhood and elementary education.

Throughout her work as an educator, she has developed curriculum and instructional programming, provided instructional coaching and professional development for elementary, middle, and high school principals and their teachers, served as a reading specialist and education activist, and taught primary grades.

The Village Schools is an educational ecosystem that provides a safe and nurturing space for students to learn to navigate the world within an environment filled with grace, love, and mercy. The Village Schools’ exploratory, supportive, flexible setting lets students learn in diverse ways and prepares them with the skills needed to thrive in a future of growing complexity. Our school community loves, protects, and understands the global majority and historically marginalized students.

Joe Connor

Joseph is a teacher and lawyer who loves helping great educators start schools. Joseph previously founded SchoolHouse, an at-home microschool company, and helped them scale to over 50 schools in 9 states. He started his career as a teacher and school leader at KIPP and Rocketship Education. He has also worked as legal counsel for school organizations and companies, including Match Education, AltSchool, the Notre Dame Ace Academies and Primer. He has a passion for helping great teachers broaden their reach.

Heather DeNino

Heather DeNino founded Elements Academy, a private preK-12 microschool and family wellness community located in Braintree, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston. Heather has been a former teacher and special education department chair in the Massachusetts public schools for more than a decade who realized that learning could and should be different.

Andrew Lee

Andrew Lee is an Arizona native, Eagle Scout, ex-rocket scientist, professional artist, and educator. He holds a B.S.E. in aerospace engineering, M.Ed. in Secondary Education, Harvard Certificate in School Management and Leadership, and is a fellow at 4.0 Schools and High Tech High’s New School Creation Fellowship. He has taught math at public, private, charter high schools, and as faculty at Arizona State University. One of his painting clients was the Phoenix Suns.

April M. Jackson

With more than a decade of experience in education as an English teacher, project based learning facilitator, academic and literacy coach, April specializes in culturally responsive teaching, curriculum design, and educator coaching.

She holds a BA in English from Miles College and a MA in Secondary Education and MA in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Phoenix.

In 2020, she also established PASS Network to improve parental engagement in education, provide student support and enhance teacher development. In 2021, she then founded the non-profit PASS Network Foundation to specifically address the academic, emotional and enrichment needs of children in underserved communities and opened the first PASS Pod, a microschool designed to ensure students receive a culturally relevant and academically challenging learning experience.

April is the co-founder of Black Microschools ATL, a collective of independently owned, non-traditional learning spaces for children in the Atlanta area.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.