Career Pathways In A Rapidly Changing World: US Career Pathways Story

Key Points

-

There has been a move away from the traditional “Bachelor’s or Bust” mentality towards recognizing the value of diverse career pathways that may not necessarily require a four-year degree.

-

Local entities such as states, school districts, and private organizations have played a crucial role in implementing and scaling up career pathways programs.

By: Paul Herdman

The U.S. Career Pathways Story: Federal Inspiration, Local Innovation

In the last decade, the United States has seen a massive shift in the national consciousness around college and careers. Many of us in the education reform community were focused on a “Bachelor’s or Bust” mentality. That is, that the attainment of a four-year degree was the only bar to shoot for; anything less was seen as selling our kids short. A few shifts have started to change mindsets:

- Cost. While having a four-year degree or more is still helpful in the labor market, college costs and related debt have made four-year degrees less attractive. (See McKinsey analysis here.)

- Options. The labor market has evolved such that in addition to high-skill, high-wage jobs and low-skill, low-wage jobs, there is a growing “middle-skill” sector of good jobs in IT, healthcare or advanced manufacturing that have good compensation and career trajectories, and require some education and training beyond high school, but not four years. (See more on this from Bob Schwartz.)

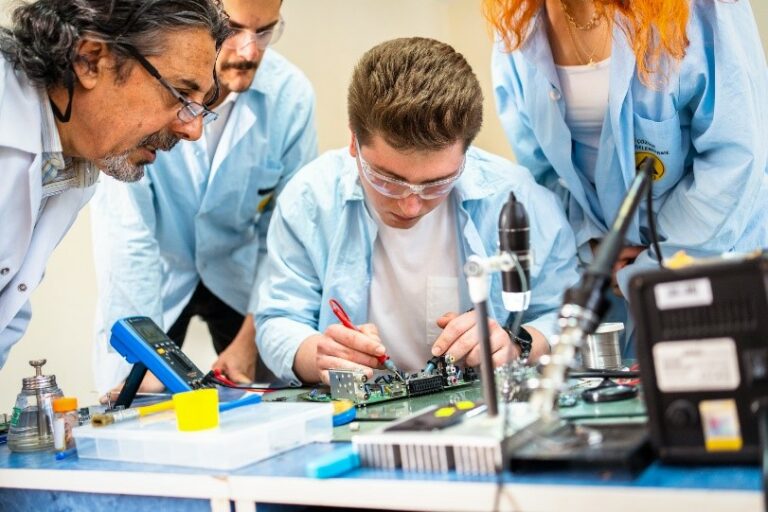

- Investments. Philanthropy, employers, and national (federal) and sub-national (state and local) government have invested in the idea of blending real-life, career-connected learning into the general education system. The reason? A growing awareness of the gap between what employers need and what young people are getting in secondary school. (See Jobs for the Future’s “The Big Blur” for more and OECD longitudinal analysis.)

While much has been written on this topic (see resources below), this post, in the context of our OECD study of five Anglophone countries, will attempt to provide a backdrop on what was happening at the federal level in the U.S. over the last several decades to help catalyze this shift in career pathways and offer a snapshot of how this work is evolving in two very different states—Delaware and Texas.

With over 330 million people spread across 50 states, this is a story of local innovation inspired by a federal framework. To understand what’s happening in each of the states, it’s helpful to understand how education policy decisions are made in the U.S.

Federal versus local decision-making. To start, the U.S. Constitution was silent on the role of the federal government in public education when it was signed in 1787. Eighty years later, in 1867, a U.S. Department of Education was established with a staff of four to capture statistics on how the nation’s students were doing. Today, 150 years later, after increased funding for low-income students in the 1960s, and deep investments to increase equity of access based on race, gender, ability, and language status in the 1970s, this federal agency, while still the smallest cabinet-level agency, has over 4,400 staff and an annual budget of about $68 billion USD.

That said, the influence of the federal government on how states and localities educate their children is limited. In terms of every dollar spent on a public school in the U.S., only about seven to 10 cents comes from the feds with the remainder largely split, about 47 to 45 percent, between local and state, respectively. This bent toward local control is compounded by the fact that these schools are governed by over 20,000 local education agencies (about 13,300 school districts and 7,800 charter schools). In short, the system is designed to put decision-making in the hands of locals. In theory, this creates a very responsive system, but it also contributes to a highly variable one in terms of strategies and outcomes.

When it comes to connecting work-based learning with general education, one could argue that its origins have been around for a couple centuries. The closest forerunners to today’s career pathways are Career Academies, which were started in the late 1960s in Philadelphia and expanded significantly in the ‘80s through organizations like National Academy Foundation (NAF). Like the career pathways of today, they blended career education with meaningful work-based learning, but they tended to comprise small learning communities within schools, while today’s career pathways tend to incorporate early college access, be offered schoolwide and be more embedded in statewide strategies.

Building on the Carl D. Perkins Act of 1984, a federal act that provides funding for career and technical education to secondary and post-secondary institutions to prepare students for the workforce, in 2014, a federal Working Group was created to deepen this effort. Consisting of the White House National Economic Council, the Office of Management and Budget, and 13 federal agencies (including Education and Labor), this group informed the definition of a career pathways system with the signing of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). This framing and an initial national investment of about $2.4 billion USD helped catalyze action across the states.

Delaware. In Delaware in 2014, local leaders were still recovering from the economic crisis of 2009 and had growing concerns about the disconnect between young people graduating high school and the world of work that awaited them.

In response to concerns of then-Governor Jack Markell and influential business leaders, namely members of the Delaware Business Roundtable Education Committee (DBREC), delegations of Delawareans started to visit and learn from countries like Singapore, Switzerland and Germany that were doing a better job of blending education and workforce development.

In 2015, Governor Markell put a stake in the ground with his Delaware Promise to ensure that 65 percent of 25–34 year-olds in Delaware had a degree or certification by 2025.

There was already a pilot program in which 27 students at the state’s largest high school were learning about Advanced Manufacturing through a partnership with a local community college and a growing energy company. The idea had promise and significant room to grow.

Luke Rhine, Delaware’s Director of Career and Technical education at the time who joined me as a part of the Switzerland delegation (and is now a Deputy Assistant Secretary in the U.S. Department of Education), shared the following on those origins:

Many of the folks leading the charge in the state wanted to ensure that we were benchmarking ourselves against those that were leading internationally and not just nationally. So, from day one, I have always enjoyed the perspective that we want to be the best in the world, not the best in our given region.Interview, August 2023

Over the next decade, a mix of public and private players worked together to develop a common vision for what a comprehensive system of career pathways could look like. In partnership with the Pathways to Prosperity Network, a national partnership with Harvard University and Jobs for the Future, Delaware created a common strategic plan and worked across industries through a cross-sector steering committee to implement the plan. (For more details, see Bellwether Education Partners’ Policy Playbook on Delaware that articulates seven strategies to create, implement, scale and sustain career pathways here.)

There were several key inflection points in the growth of the career pathways movement in Delaware:

- Initial catalytic investments from national philanthropy: Investment company JP Morgan Chase and national foundation Bloomberg Philanthropies helped Delaware launch a statewide Office of Work-Based Learning within Delaware Technical Community College and, in addition to supporting pathways broadly, helped the state build out more immersive pathways in healthcare, much of which is now supported by state funding.

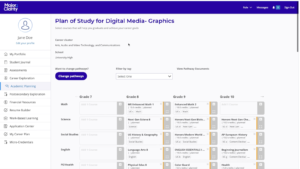

- Braided funding from the Department of Education involved aligning the metrics for all the federal funds that typically go to the schools with siloed, discreet reporting requirements. By aligning those funds around common metrics, more dollars were available to schools, and the DOE then worked with each district or charter school to implement the state-approved career pathways model in a simple-to-implement structure.

- Pathways 2.0 was launched in 2021. Amid COVID-19, when the potential for pathways to stall because students couldn’t be in school or work placements, Rodel worked with several national foundations (Bloomberg Philanthropies, Walton Family Foundation, and American Student Assistance) to secure $7.5 million USD against a $15 million USD plan for 2022-25, for which current Governor John Carney invested the remaining $7.5 million with federal American Rescue Plan dollars. This enabled the state to start pathways earlier in the middle grades; go deeper with employers by launching the new Tech Council of Delaware (TCD) to better link young people with the growing tech sector; and go faster with the acceleration of apprenticeships. (See full case study here.)

In 10 years, Delaware has grown from that pilot of 27 students in one pathway to over 30,000 students or close to 70 percent of its secondary students in 24 career pathways that involve a meaningful work-based learning experience, a cluster of three career and technical courses, industry-recognized credentials, and access to postsecondary courses.

While every high school in the state now offers career pathways, the challenge going forward is to build the policies and systems to continue to equitably scale and sustain the work.

Texas. In Texas, a mix of philanthropic investments was also catalytic to piloting some innovative approaches, and those ideas were scaled with some thoughtful legislative actions.

Back in 2003, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle, Washington, helped create the Texas High School Project at the Texas Community Foundation. (See more on the THSP here.) These efforts led to new partnerships among high schools and higher education institutions called “early college high schools.” The initial motivation behind ECHS’s was the need to address the declining graduation rates for Texas high school students, as well as the low percentage of minority, low-income, and first-generation students earning higher education degrees or credentials.

In 2010, the THSP relaunched as Educate Texas to better represent the broader scope of work needed to improve the system. Similar to the Delaware Promise, and inspired by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s 60X30 plan (2015), Educate Texas worked with the state to achieve their collective goal of 60 percent of Texan 25–34-year-olds holding a degree or credential by 2030.

To help meet this goal, Educate Texas partnered with a cross-section of leaders to expand the P-TECH model, or Pathways in Technology Early College High School (a model started in New York City in 2011). This involved building formal, three-way partnerships with employers, high schools, and higher education partners. The primary focus of these partnerships was to work with high-need students and connect them to high demand occupations, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM).

The first P-TECH school in Texas was started in 2016, and today, just eight years later, there are 276 (and 236 ECHS). Because there are more than 5.5 million students in Texas, the student population served by P-TECH schools is less than five percent, but the question remains, how did the model grow so fast?

While there are likely several drivers, one appears to be that legislators have leveraged the proof points established by philanthropic investment into legislative actions.

Ryan Franklin, Senior Director for Policy and Advocacy at Educate Texas described it this way,

One of the things Texas has done well over time is support the front end of legislation and then reward the back end as a way of sustaining it. For example, the legislature will do things to invest in technical assistance on the front end and a state investment might pair with a philanthropic investment to expand it. Multiple systems coming together are so necessary to making a change.Interview, February 2024

This has played out in several laws:

- House Bill (HB) 3 (2019), which incentivized college, career and military outcomes at the high school level and provided support and funding for the creation of P-TECH schools

- HB8 (2023), which changes how community colleges are funded around similar outcomes

- HB2209, which codified funding to incentivize the creation of new pathways partnerships in rural communities known as Rural School Innovation Zones

That said, Ryan shared that there’s still work ahead. He stated that, “while the legislation of the last several years has moved us forward, there are still some efforts needed to better align the outcomes between secondary and postsecondary education.” (Interview February 2024)

Big picture. While the federal government has significant influence through a range of investments like Perkins, Pell and WIOA, and a coherent, four-part federal strategy called Unlocking Career Success, federal funds are typically dwarfed by the state and local funds going to educate American students. As Amy Loyd, Assistant Secretary of Education at the Office of Career Technical and Adult Education, at the U.S. Department of Education shared with me in an interview in August 2023:

It’s fascinating to see how different states engage in the work. Education in the United States is almost entirely the purview of states to determine. States hold the reins in our education system.Interview, August 2023

As I step back and look at how the U.S. compares to the other four Anglophone countries in this study, three differences stand out.

Secondary and postsecondary education are more blended. One, with the exception of a growing “dual credit” effort in Canada, the career pathways effort in American senior secondary schools has intentionally been integrated into credentialing and credit attainment in higher education much more so than the other countries. Given that 72 percent of the jobs in the U.S. will require education or training beyond high school by 2031, this seems appropriate.

Philanthropy plays a much bigger role. Two, as stated above, not only does governance tend to differ in the U.S. by encouraging more local control than countries with heavier national influence like Scotland, but philanthropy doubles down on the variability by investing in many innovative new approaches. With more than 119,000 private grantmaking institutions in the U.S. collectively giving out close to $34 billion USD a year* to education in no particular way other than the subjective determinations of those grantmakers, it’s not surprising that the U.S. produces a lot of creative pilots. Where the U.S. tends to struggle is taking those ideas to scale.

Intermediaries are critical to connecting the dots. And third, this set of conditions has likely contributed to the importance of “intermediaries” at multiple levels. While all five of the countries in this study had organizations that served to connect the schools, employers and higher education partners, the funds for these efforts in the countries other than the U.S. largely came from the public sector and were therefore consistent within a given jurisdiction.

In contrast, in the U.S., intermediaries tend to largely be funded by a mix of public and private sector funds, and they exist at multiple levels. At the state level, Educate Texas, Rodel and Delaware’s Office of Work-Based Learning connect the dots among national and local funders, build relationships with employers and school districts, and also help advocate for systemic change. Local or regional intermediaries, like the Rural Schools Innovation Zone in South Texas or Code Differently in Delaware can connect employers with schools, manage work-placements, and in some cases, serve as the employer of record. Collectively, these state and local entities attempt to create seamless experiences for students from high school to higher education and a career.

National intermediaries also play a critical role by networking across regions and states. Through organizations like Pathways to Prosperity Network, Strada, Policy Innovators in Education Network, Grantmakers For Education, Jobs for the Future or Education Strategy Group, the U.S. works to accelerate our collective learning curve and stitch together a patchwork quilt of a national strategy. It’s colorful and creative, producing a lot of inspired and smart approaches, but coherent and aligned, it is not.

A U.S. challenge and a two trillion-dollar opportunity. The inherent structural challenge in the U.S. is that it is designed to be controlled locally and therefore filled with many small-scale innovations, but slow to make fundamental, systemic changes.

However, since 2020 in response to climate change, concerns about global competitiveness, and an aging infrastructure, there are over two trillion in USD going into a range of new efforts to reduce carbon emissions, like investments in clean Hydrogen hubs and electric vehicle charging stations, as well as investments in infrastructure and efforts to improve our global competitiveness such as new investments to build semiconductors. Across all these investments, workforce training is required, and the people needed to do the work are simply not yet there at the scale needed. This represents a big opportunity to accelerate U.S. career pathways efforts. If some states can build the policies and systems needed to seamlessly connect the interests of secondary students to these high demand fields, we could see a large-scale shift in how Americans navigate from school to a career.

This blog was originally published on Rodelde.org.

Paul has been president and CEO of Rodel of Delaware since 2004. He is a founding member of the Vision Coalition, one of the nation’s longest standing public-private partnerships. The group works to transform Delaware’s public schools to world-class status.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.