Karema Akilah on Decentralized, Human-Centered Learning Environments

Key Points

-

Kids need to be trusted that their curiosities are enough.

-

Sometimes the mother needs to retire the teacher.

This episode is supported by our recent Artificial Intelligence publication which focuses on the ways in which AI is shaping teaching, leading and learning.

On this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, Nate McClennen is joined by Karema Akilah, founder of the Genius School, Genii DAO and Geniiverse. We first met Karema at ASU+GSV and were struck by her creative “genius” in pulling together homeschools, Web3, metaverse worlds and all around commitment to learner agency, purpose and difference making.

Know your world and how that has impacted you.

Karema Akilah

Transcript

Nate McClennan: You’re listening to the Getting Smart podcast, and I’m Nate McClennan. Web3 has been significantly overshadowed by AI in the last six months, but it’s still moving fast to build the next generation of the internet designed around self-governance, individual control, and decentralized models that eliminate intermediaries. What does this mean? Ultimately, it may allow learners to connect directly with educators, document evidence of any type of learning in any location—both online and in the real world—and give learners control over their pathways to the future. This is very different from the existing compliance-based, top-down structure that exists for most young people in modern education.

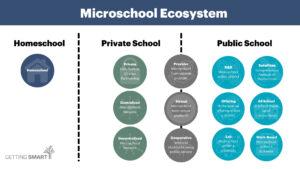

So, what happens if you combine Web3 with the microschool revolution, where it’s estimated that close to two million young people are now enrolled in some form of micro school? Typically, these are low-fee, private, small learning environments where young people might learn with others in a digital metaverse while working on community impact projects in the real world. They might design their own learning paths and connect directly with experts who can help them along the way. They could even lead, direct, and collaborate on the future of the structure within which they learn. We’re a long way from this being widely adopted, but innovative educators are exploring and learning in this space. Today, I am so excited to be joined by Karema Akilah, the founder of the Genius School, the Genie DAO, and the GenieVerse.

Nate McClennan: Karema, I met you at ASU+GSV, and I was struck by your creative genius in integrating homeschools, Web3, metaverse worlds, and an all-around commitment to learner agency, purpose, and impact. I’ve been waiting for this conversation for a long time. Welcome—I’m excited to have you.

Karema Akilah: Oh, Nate, thank you so much. It’s such a pleasure to be here! I’m excited to share what we’re up to. Thank you.

Nate McClennan: Great. To start off, I’m always interested in stories of learners. Can you share a story about a learner in your community—one that really amazes you?

Karema Akilah: That’s a tough question because the learners are so amazing. I’ll pull from two places. We have a metaverse, which we call the GenieVerse—a 2D metaverse—and then we have micro schools in Kampala, Uganda. What fascinates me about both locations is the transformation in the learners. In Uganda, for instance, we work with children who can’t afford to attend government schools. Some of these kids are as old as sixteen or seventeen and are just learning to write their names for the first time. In those schools, it’s common for teachers to use corporal punishment, but we don’t practice that. The kids are amazed that they aren’t ridiculed or criticized as they learn basic skills. Shout out to our genius directors in Kampala.

In the GenieVerse, we have two amazing kids—Battle Stevie and his twin sister, Miss Kat. They live in Canada and are the kings and queens of YouTube. During our YouTube corporation meetings, I take notes because they teach me things like how to add the end cap to videos. And then there’s Ezra, whose father is contracting with the army, so he’s been living in Poland. We’re his only community. Ezra is about seven years old, and his social and emotional growth in our metaverse has been fascinating. When he first joined, he was clingy and would follow my avatar everywhere. But now, he’s become a social butterfly. He greets new kids in the metaverse and has even started reading while playing Roblox and Minecraft. Watching him read fluently was amazing, and I sent his mom a message saying, “I think we have a reader on our hands.”

There are so many learners I could talk about, but what fascinates me most is their ability to harness creativity, use adult tools, and play with technology as if it’s second nature. My job is to translate what they’re doing in play into something their parents can understand.

Nate McClennan: That’s beautiful. In just a couple of minutes, you’ve mentioned impacts on learners in Uganda, Poland, and Canada. And you’re calling from Atlanta in the United States! It’s powerful to see the different ages—from sixteen-year-olds in Uganda to a seven-year-old in Poland—all learning at their own pace to reach their goals.

You know, I haven’t met anyone in education who has combined the things you’ve combined. Sometimes, I think creativity is about combining existing things in unique ways, and you’ve done that. What’s your journey? How did you end up facilitating a metaverse, running a micro school network, and all the other elements in your world of work and life?

Karema Akilah: How much time do we have? I’ll try to make this as succinct as possible. I’m a former public school teacher with a degree in elementary education from Morgan State University—an HBCU in Baltimore, Maryland. I started teaching in Maryland public schools, first in first grade, then in fifth. When my husband and I had our oldest, I became a stay-at-home mom. Our son was born in December, which meant he was almost six when he could start school. By that time, he was already reading, so I knew the public schools wouldn’t be able to accommodate his level. That’s how we began homeschooling.

Now, Nate, I have to tell you about my homeschool experience. I recreated traditional public school in my home to the point that I had the kids dressed in uniforms, looking like they worked at Target or Walmart, to sit at the dining room table. We were academically successful, doing rigorous classical education, but something was missing. My kids were checked out—they were lethargic learners. I realized they never got to be curious or passionate. And as their mom, I never got to be the fun, relaxed mom either.

One day, I decided to try something new. I sat my kids down and said, “On Monday, we’re going to try classical mornings and delight-driven afternoons.” The younger ones were excited, but the older ones were skeptical. When we started, I taught classical subjects in the morning, but after lunch, the kids took charge of their learning. I saw the light come back into their eyes. They were curious, joyful, and engaged.

Then one day, the kids got clever. They started delight-driven learning before breakfast. I thought, “If I stop this, I’ll be stopping real learning just for the sake of teaching.” So, I retired as the teacher and fully embraced unschooling—self-directed learning based on curiosity and joy.

In 2015, my husband was diagnosed with leukemia. We made frequent trips to the hospital, which meant I wasn’t home as much to interfere with their learning. My children blossomed. When my husband passed away in 2016, I became a single mom and continued unschooling. I wondered what to do if I had to return to work, and I realized the nearest alternative school was too far. That’s when I came up with the idea for the Genius School—a place where kids could discover their genius, whether it was intellectual, creative, or practical.

I originally planned to create just one school, but then I had a conversation with God, and I felt called to build more. Instead of perpetuating the problem by creating just one, I wanted to build a system anyone aligned with self-directed learning could replicate. So, that’s how the Genius School model came about.

When I moved to Atlanta in January 2020, we held our first interest meeting, and then COVID hit. It was a blessing in disguise because suddenly, parents were home educating, and they began to see the value in what we offered.

Nate McClennan: What an amazing story. I’m so sorry for the tragedy but excited for the joy you bring through this work. Thank you for sharing your story. I believe deeply in stories, and yours is inspiring.

I loved the idea of the “mother retiring the teacher” and the concept of delight-driven afternoons. You mentioned the five pillars—could you describe those?

Karema Akilah: Sure! The five pillars came from my desire to prepare my kids for adulthood. Learning is an internal process, so I focused on offering invitations rather than mandates.

Pillar 1 is Know Thyself: discovering who you are, your strengths, and what you’re good at through “good experiences.”

Pillar 2 is Know Your Source: self-care in emotional, mental, social, and physical aspects.

Pillar 3 is Financial Sustainability: understanding money management and career options, whether as an employee, self-employed, business owner, or investor.

Pillar 4 is Know Your World: older learners complete autonomous field trips called expeditions to explore their communities and document their experiences.

Pillar 5 is Serve Your Community: learners use their genius to address a community problem pitched by a local leader, creating a viable product or service in response.

Nate McClennan: I love the structure of looking inward, then outward. As you grow your micro school network, will each school adopt these pillars? Will they look the same in each location?

Karema Akilah: Yes, each is a five-pillar Genius community led by a Genius Director who invites learners to participate in the pillars. The framework is consistent, with the same structure and flow, but each school tailors the pillars based on local resources. All physical communities are also connected through the GenieVerse, allowing students to participate virtually in corporations and activities across locations.

Nate McClennan: Got it. So the GenieVerse is asynchronous, right? There must be planned meetings where a site or learner can start something and promote it within the network, making it available to anyone who wants to join.

Karema Akilah: Exactly, and the GenieVerse also has its own community. For example, we have learners in Poland and Canada who aren’t part of a physical school. They’re only members in the GenieVerse. So yes, they can fully participate without needing a physical site.

Nate McClennan: That’s fantastic because it’s all about access. If someone can’t physically get to a site, like your learner in Poland, they can still feel part of a community and engage in a larger network.

Let’s talk a bit about Web3. You also have a DAO—a decentralized autonomous organization. How does that fit into your model?

Karema Akilah: Great question. The idea of Web3 came to me back in 2016 or 2017, even before terms like DAO or decentralized were common. My developer back then suggested using blockchain, saying, “You could use this tool to help students document their learning, validated by a third party.” So, I’ve always had a foot in the Web3 space.

When Web3 became what it is today, I saw an opportunity to step into this space with the Genie DAO. Our DAO serves as our Web3 arm, aiming to use decentralized tools to enhance awareness, accessibility, funding, documentation, and diversity—especially funding. We’re in the early stages of a $5 million raise in our crypto wallet, inspired by ConstitutionDAO. We hope to reach our goal by September to fund scholarships and support our schools.

Additionally, we’re looking at incorporating blockchain and AI into the Genie app to allow self-directed learners to document their learning in a way that translates into language that both state systems and colleges can understand.

Nate McClennan: So just to clarify, people contribute by buying NFTs or something similar to be part of the DAO, and those resources fund the Genius School, the Genie DAO, the GenieVerse, etc.?

Karema Akilah: Exactly. Our goal is to create a sustainable funding model for scholarships so families who can’t afford it can still access our programs.

Nate McClennan: I love that—it’s a great use of a DAO for social good. I’m curious about the Genie app. Does it serve as a digital wallet for learners, allowing them to take their documented learning with them when they leave the Genius School?

Karema Akilah: Yes, that’s exactly where we want to go, though we’re not there yet. Right now, our immediate goal is to integrate AI, making it accessible even to centralized public schools. My experience as a public school teacher showed me how hard it is to document each learner’s unique work, especially with project-based learning. The Genie app could change that by helping teachers and students keep track of learning in a meaningful way. Once we have enough funding, we’ll add blockchain capabilities to make it a true digital wallet.

Nate McClennan: I appreciate that vision of linking personalized, decentralized learning to the existing system. It could really scale if public schools see the value. Do you envision a scenario where Genius School could coexist within the public system, like a Genius School classroom?

Karema Akilah: I wrestle with that question a lot, honestly. Self-directed learning, at its core, is non-compulsory, meaning it’s based on choice, not mandates. Public school, by definition, is compulsory: students have to go, learn a set curriculum, and demonstrate understanding through standardized means. However, there might be room for flexibility if schools are open to offering blocks of time for freedom and blocks for structure. We do offer Genius Consulting for schools interested in decentralizing their curriculum, putting the learner at the center, and offering more freedom within the system.

Nate McClennan: It’s a big question. Research shows that people learn better when they feel capable, have control, and feel positive about learning. Yet most schools operate on a compliance model rather than an agency-based one. I feel hopeful that, in time, more public schools will consider integrating these principles.

Switching gears, I noticed something on your website about “decolonizing parenting.” As a parent of teens, I’m really interested in this idea. Can you share more about what you mean by decolonizing parenting and how it fits into your work?

Karema Akilah: Absolutely. My friend Akilah Richards wrote a wonderful book called Raising Free People, which explores this concept deeply. Colonized parenting typically doesn’t give children much choice or voice. Decolonizing parenting means inviting kids into conversations, respecting their agency and consent, and valuing their input in family decisions. While I still make the final decisions as a parent, I do it transparently and with my kids’ voices in mind.

This approach is crucial to the Genius School philosophy because parents often love the idea of self-directed learning and the independent, confident learners it produces. But they sometimes struggle with the same agency at home. If parents haven’t created an environment that sustains this way of being, they might feel challenged by the freedom their child brings home. That’s why we offer decolonized parenting and deschooling coaching twice a month to help families unpack and embrace this approach.

Nate McClennan: That’s such a great concept. I can see how parents might like self-directed learning in theory but find it challenging when it conflicts with traditional norms at home. I really appreciate how you articulated that.

We could probably talk for hours, but we’re nearing the end of our time. I always like to close with two questions. First, what’s the biggest takeaway for our listeners based on today’s conversation? Second, who has been an inspiration to you—someone who may not get a lot of recognition?

Karema Akilah: Thank you, Nate. I would say the biggest takeaway is to embrace the hunt for authenticity. With the school year ending, I encourage parents, teachers, and administrators to ask themselves what isn’t working. Ask, “Who do you not get to be in your current environment? What’s missing that would make a difference for you?” Then, create the space to make that possibility real. You, the children, and the future of education are worth it.

As for my inspiration, I’d have to say I’m standing on the shoulders of giants. John Holt, who coined the term “unschooling” in the late ’60s, the founders of the Sudbury schools, and the Agile Learning Centers have all paved the way. Another group I’d like to acknowledge is Facebook group moderators. I know that sounds odd, but these are often parents or educators providing real-time support to other parents who are struggling, and they play a huge role in the educational ecosystem.

Nate McClennan: I wasn’t expecting that answer, but I love it. Facebook group moderators really do help people find solutions and create community in unexpected ways. Thank you for such an inspiring conversation, Karema. I feel optimistic about the future thanks to people like you. Let’s keep pursuing authenticity and asking ourselves who we want to be in this space. We’ll be sure to include links to all the resources you mentioned in our show notes.

Karema Akilah: Thank you, Nate! It’s been a pleasure—call me back anytime.

Nate McClennan: Thank you.

Links:

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.