Agency for nine-month-olds? Yes!

Key Points

-

Reggio Emilia-inspired environments, like Growing Place, support early childhood development by fostering agency and deeper learning through inquiry-based learning and provocation-rich settings.

-

Investing in teacher training and professional development enhances the quality of early childhood education, benefiting both educators and children by encouraging innovative practices and strong educator support systems.

America’s education system was a groundbreaking effort to help a growing nation thrive in the 19th century. Now, 200 years later, the world has changed; the horizon looks drastically different. Collectively, we need to redesign our education system to enable all of our children — and, by extension, our nation — to thrive today and tomorrow. “Horizon Three” or “H3” names the future-ready system we need, one that is grounded in equity serving learners’ individual strengths and needs as well as the common good. This series provides a glimpse of where H3 is already being designed and built. It also includes provocations about how we might fundamentally reimagine learning for the future ahead. You can learn more about the horizons framing here.

Blog and all photos by: Losmeiya Huang

The twin strands of H3 education’s DNA are student agency and deeper learning. Reams of research show that 0-5 are critical years in a child’s development. How do these two puzzle pieces fit together? What is agentic, deeper learning for a nine-month-old or a terrible (wonderful) two-year-old?

An earlier post in the series discussed Reggio Emilia, a tiny region in Italy known for its deeply human, learner-centered early childhood education – a movement that started from a small group of mothers coming together to create their own community-based preschool. Growing Place is a great example of what Reggio Emilia looks like in action. This network of three early childhood education centers, founded 40 years ago, sits just outside of Los Angeles and partners with the City of Santa Monica, Santa Monica Community College, the Rand Corporation, and CalTech. In this post, I want to share what human interactions and learning in Reggio look and feel like so you can get a sense of how we intentionally nurture the littlest ones’ curiosity and agency. Then I’ll discuss how we might scale these deeply developmental learning experiences to much larger populations.

Reggio Principles from Infants to Preschoolers

At the Growing Place, we see agency as a fundamental part of child development, even in infancy. By integrating provocation-rich environments and inquiry-based learning with young children’s natural curiosity, we create learning experiences that encourage them to make choices, explore, and feel ownership over their learning. Each developmental stage has its own essential questions, described below.

Infants: “Who am I?”

Infants, ages 6-18 months, are navigating the world for the first time. They’re developing a sense of self, and the essential question guiding their development is, “Who am I?” Even at this stage, we see infants as capable of engaging with the world around them. For example, during diaper changes, we don’t just pick up the child without notice. Instead, we narrate the process, “I’m going to pick you up and put you on the changing table. I’m taking off your diaper now – can you support by lifting your legs?” This simple act of inviting the child to participate, of communicating with the child rather than just getting something necessary done to the child, acknowledges the child’s autonomy and fosters a deeper connection between adult and child, child and their world.

One day in the infant room at the Growing Place, a nine-month-old named Lily was sitting up, reaching for a wooden block just out of her grasp. After a few attempts, she managed to get hold of it. She then looked around to figure out what to do next. She began scooting her little body over toward her teacher, not a simple task for a nine-month-old. With a smile, she offered the block to the teacher, her eyes bright with excitement. The teacher, trained to understand that this wasn’t just a casual gesture, leaned in and accepted the block. “You gave me the block! It’s smooth and flat, and you scooted all the way over to share it with me,” the teacher narrated, before offering it back to Lily.

Lily is beginning to understand that her actions—her decisions to grasp the block and offer it—hold meaning, and that she can connect with others through them. This is an early form of agency, her first step in answering the question: “Who am I in relation to others?”

Losmeiya Huang

Lily then handed the block back to the teacher, beaming, wanting to repeat the game. To a casual observer, this might seem like a simple back-and-forth exchange, but to those who trained in early childhood development, this moment is full of significance. Lily is beginning to understand that her actions—her decisions to grasp the block and offer it—hold meaning, and that she can connect with others through them. This is an early form of agency, her first step in answering the question: “Who am I in relation to others?”The teacher’s role was key in facilitating this deeper learning experience. By carefully observing Lily’s actions and responding in a way that encouraged further engagement, the teacher provided the infant with a chance to experience the power of her own actions. These sorts of exchanges happen hundreds of times a day with infants and adults across our campuses. With increasing neuroscience research, we know that this “serve and return” is a proven mechanism that builds strong brain architecture.

Toddlers: “What are these big feelings in my body?”

As children move into the toddler years (18-36 months), they begin to explore new emotional and physical experiences, often grappling with the questions: “What are these big feelings in my body? How do I share attention?” At this stage, they are learning to express emotions, navigate boundaries, and understand how to engage within a social group.

We design the environment to match their natural curiosity and need for full-body engagement. For example, we roll out large sheets of paper across the floor and provide long paintbrushes. Toddlers don’t just paint with their hands—they move their entire bodies. They walk, crouch, and stretch, using the brushes to create sweeping strokes. As teachers, we observe, narrate, and respond: “Look how you’re making such long, colorful lines. Your body is really moving as you paint!” This narration helps toddlers become aware of their physical actions and encourages them to see how they can shape their environment.

We also take great care in designing the room from a toddler’s perspective. Teachers lower shelves and tables to toddler height, ensuring that children can easily access materials on their own. We crouch down and walk through the classroom on our knees to get a sense of what the space feels like from their viewpoint. By doing this, we’re better able to see obstacles that might feel overwhelming to a two-year-old or spaces that are too open and might lead to overstimulation. For instance, we often add cozy nooks with soft fabrics draped from the ceiling to create small, enclosed spaces where toddlers can retreat and feel safe. These little corners help toddlers manage the sensory overload of a busy classroom and give them a chance and space to self-regulate.

We also help toddlers navigate their emotions, particularly when they experience big feelings like frustration or joy. For example, if a child gets upset over not having a toy, we don’t just step in to resolve the issue. Instead, we help them articulate their feelings: “I see you’re upset because you want the truck, and you’re frustrated because someone else is using it. It’s hard to wait, isn’t it?” This helps the toddler begin to understand, name, and manage their emotions, fostering empathy and teaching them how to share attention.

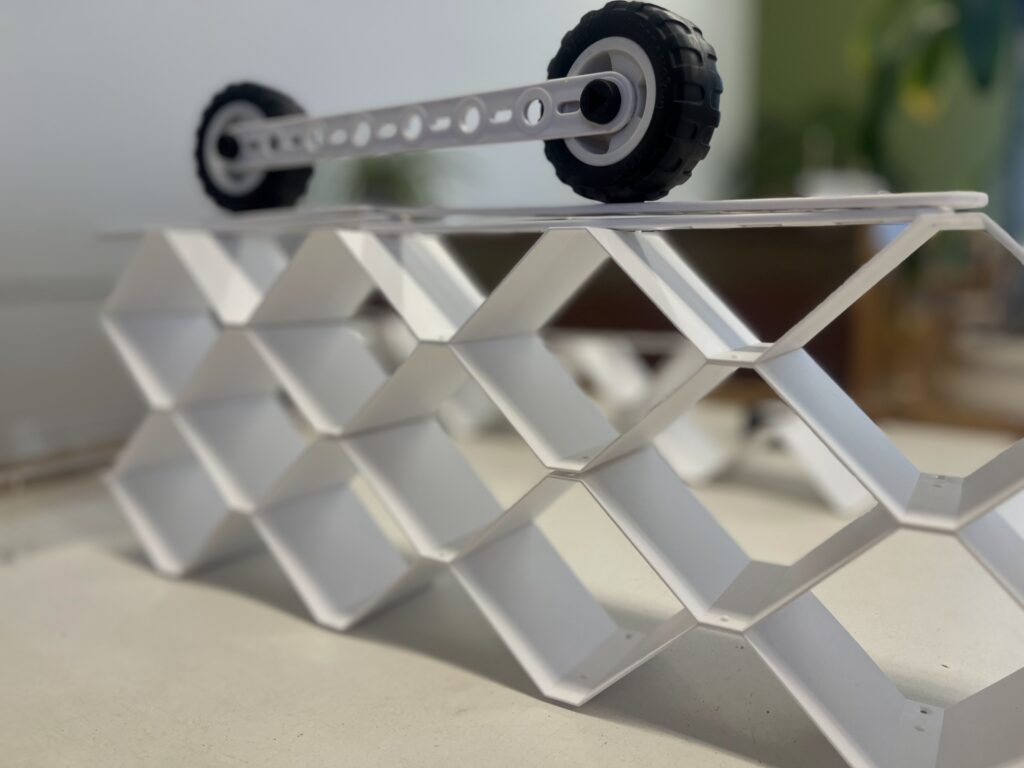

In every part of the environment, we provide provocations that encourage toddlers to explore and engage with others. Whether it’s blocks, clay, or other materials, we create opportunities for them to interact, share space, and learn together. By doing so, we help them answer the essential question, “How do I belong?” while fostering their emerging sense of self and connection to others.

Preschoolers: “What is my purpose? Am I good or am I bad? What does it mean to be part of a group?”

As preschoolers, children aged 3-5 are beginning to ask deep, abstract, and emotional questions about their identity and role in the world. This developmental stage is critical for exploring concepts like responsibility, contribution, and social belonging.

One way we help preschoolers process these emotions is by offering them opportunities to reflect on their behavior and feelings. For example, when a child says, “No one ever wants to play with me,” we guide their emotional development and thinking by asking, “How do you know no one ever wants to play with you?” This simple question encourages the child to reflect, helping them understand that their perception may not always align with reality. Through this reflection, the child begins to recognize that emotions like rejection or frustration are part of social dynamics, not a reflection of their worth.

Another way we help children answer these questions is by assigning meaningful classroom jobs that provide them with a sense of responsibility and purpose. For instance, preschoolers may be given the important task of rubbing the backs of two-year-olds during rest time, helping them relax and settle into their sleep. This simple yet profound act teaches them that they can comfort and care for others. It also reinforces the idea that they have an important role in the community—something that is essential for fostering a sense of purpose.

To support navigating their growing social world, we are intentional about helping children learn how to engage with peers in meaningful ways. If a child is standing at the edge of a group watching others make mud pies, instead of asking, “Do you want to play?” we guide them with, “I notice you’re watching them make mud pies. Do you want to join in? Maybe you can start making one next to them.” This approach respects the child’s autonomy while providing an entry point into the group. It helps the child answer the question, “What does it mean to be part of a group?” by showing them they can belong in a way that feels comfortable and authentic to them.

Preschoolers also begin to wrestle with the question of whether they are “good” or “bad.” These reflections often arise during emotionally charged situations at home, such as a new baby or the illness of a grandparent or the death of a pet. Even if families don’t talk about the situations, preschoolers absorb the feelings in the household and feel they’re responsible, that their behavior caused these events. In these moments, we help them understand that not everything in their environment is within their control. By carefully guiding children through these questions, we help them construct a positive, secure sense of self.

Through purposeful classroom jobs, guided social interactions, and emotional support, preschoolers learn to navigate these essential questions with confidence, building a solid foundation for self-awareness, social belonging, and engagement with the world around them.

The learning experience is not about rushing to the ‘right’ answer, but about helping children learn to ask better questions and develop the joy of discovery themselves. By guiding them through observation, documentation, and reflection, the teacher ensures that the learning is co-constructed, meaningful, and empowering for the children.

Losmeiya Huang

Deeper Learning in Action

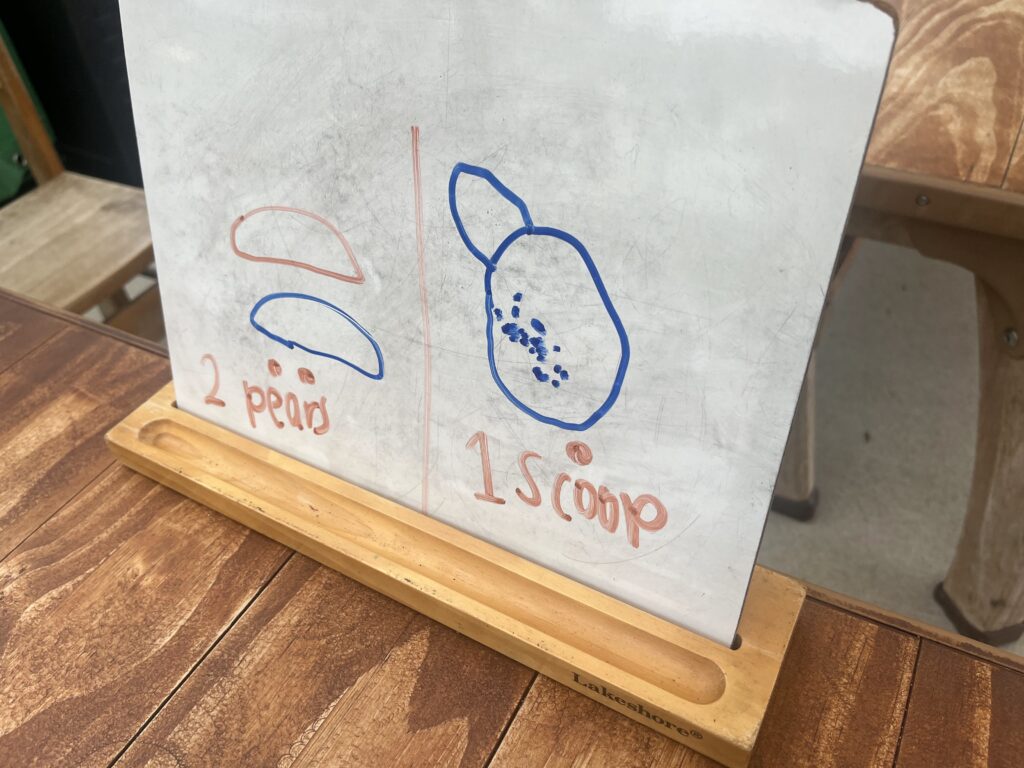

Every stage of development at the Growing Place is guided by these essential questions and students’ curiosity; they shape how we design learning experiences for our children.In the three-year-old classroom at the Growing Place, when children ask, “Where does the sun go when it disappears?”, the teacher doesn’t simply pull out a book and give a scientific explanation, as one might in a more traditional setting. Instead, she creates a deeper learning experience by facilitating an open discussion, asking questions like, “What do you think?” and “What have you noticed?” The children’s responses—”I watched the sun disappear into the ocean” and “I noticed light change during a flight”—become the foundation for the teacher’s next steps in designing their learning journey. She sets up a weather-charting activity as a provocation, encouraging the children to collect data daily, observe patterns, and gradually form their own understanding. The learning experience is not about rushing to the ‘right’ answer, but about helping children learn to ask better questions and develop the joy of discovery themselves. By guiding them through observation, documentation, and reflection, the teacher ensures that the learning is co-constructed, meaningful, and empowering for the children.

Literacy

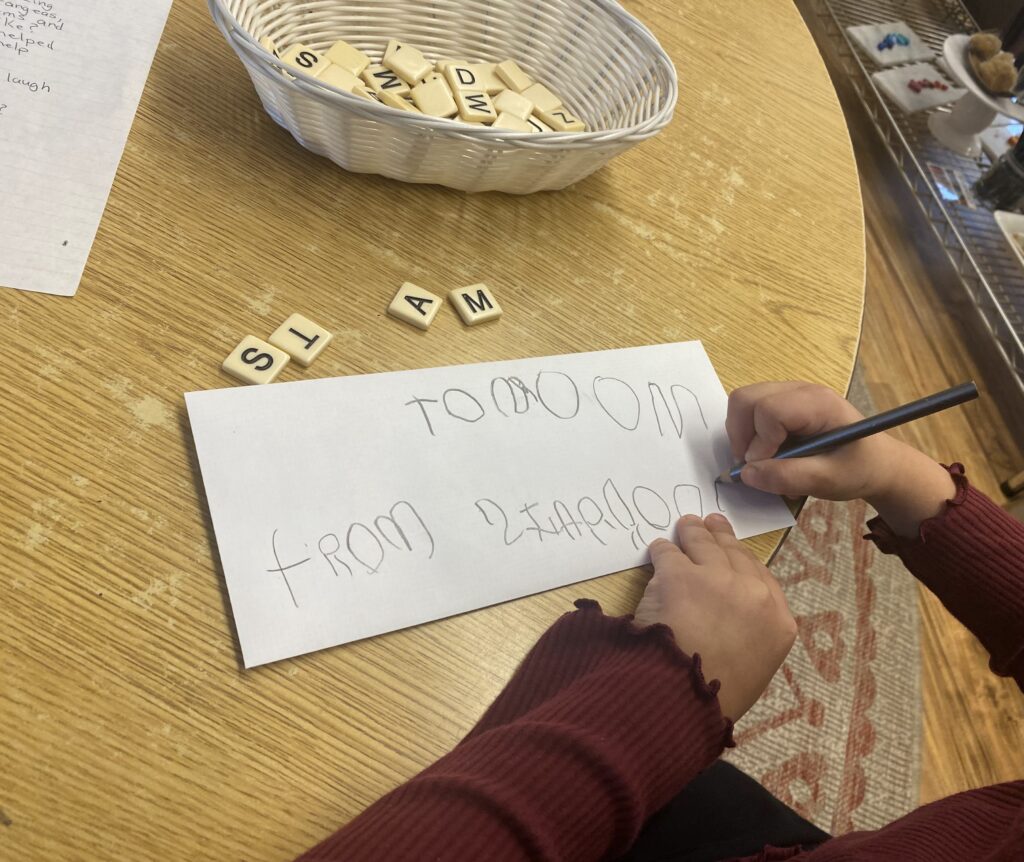

Literacy works similarly. Unlike traditional classrooms where letters and charts often dominate the walls, our literacy-rich environment is designed to allow children to naturally encounter and engage with language in a more fluid and integrated way. Instead of bombarding the space with alphabet posters or rigid rules about reading and writing, we ensure that literacy is embedded in meaningful interactions. Children at this age are beginning to realize that symbols—letters and words—carry meaning. For example, when a child misses their parent during the school day, we might say, “Would you like to write a note to your mom?” The teacher then helps the child dictate their message, “Dear Mommy, I miss you,” and together they write it down.

[…]children are free to write whenever inspiration strikes, turning literacy into an invitation rather than a mandate

Losmeiya Huang

As children’s literacy skills develop, they are encouraged to try writing on their own. A child might say, “I don’t know how to make an ‘A,'” and the teacher will respond, “Let’s do it together – which line do you want to start with, the up and down or the across one (teacher says this while tracing the lines),” guiding them through the process while offering encouragement. Over time, the children gain confidence in their abilities, transitioning from scribbles to writing letters and words, and discovering that they have the power to communicate through writing. This act of writing becomes more than just learning letters—it becomes a meaningful experience of self-expression and connection with others.

Each child has their own name card with a written name and an image, which they use daily to recognize letters and connect symbols with personal significance. These cards are at their height level, as are writing materials like crayons and paper, so children are free to write whenever inspiration strikes, turning literacy into an invitation rather than a mandate.

One day, a child named Ben brought a note with scribbles to his teacher, proud of what he had created. The teacher, knowing his capabilities, gently pushed him to go a little further. “I’ve seen you write your name before,” she said, encouraging him to try again. Together, they retrieved his name card, which had his name printed alongside a small picture for guidance. She asked Ben which letter he wanted to begin with and he chose to start with “B.” This showed the teacher he was already familiar with left-to-right directionality. Then, when he hesitated over how to form the letter, the teacher helped him break it down, asking, “Do you want to start with the straight line or the bumpy part of the ‘B’?” Ben stayed engaged, working on his name for 30 minutes, and the pride on his face when he completed the task was unmistakable. Through this simple but profound act of writing, Ben discovered not only his ability to write but also the joy and sense of purpose that comes with mastering a skill. He began with a joyous impulse to scribble and concluded with the hard work of forming his name.

How to Scale? Develop Teacher Agency with the Same Care as the Stories Above

As you can see from the stories above, Reggio practices are grounded in highly skilled observation and deeply relational behaviors. Much learning happens, academic, developmental, and relational, but in ways very different from a traditional classroom model. These practices and behaviors grow agency and strong senses of self and community, and prepare young children to embrace H3 ways of learning as they grow up. How might we bring this way of nurturing and guiding to more early childhood education centers?

We believe that it all begins with working with teachers in the same thoughtful, caring, responsive ways we want them to work with children. Teachers are humans, and we know that humans thrive when they are inspired. Teachers also have personal identities and creativity which need to be acknowledged, nurtured, and activated. Teachers whose agency is nurtured want to keep learning, follow their curiosity, and offer their contributions. Currently they are underpaid and not valued, and trained to become academic content delivery people.

At The Growing Place, we’ve built a Growing Place approach, a pedagogy and philosophy that centers children’s learning and the teacher’s observation and support of that learning, that values the deep relationship between child, parent, and teacher in order to create a thriving ecosystem at school, and that honors teacher humanity – while still delivering the California Preschool Standards for learning. Our approach supports teachers’ humanity to help them support the growth and development of the children they attend to.

The Growing Place approach is being used in a variety of locations and pathways. We partner with local high schools to encourage young adults to explore the early childhood profession. This includes students connecting with our teachers and coming on campus to volunteer their time. We’ve built multiple training pathways with our local community college, Santa Monica College (SMC), which is one of our partners in developing the next generation of early childhood educators. Here teachers learn to be facilitators of learning with both children and colleagues. The SMC pathways include classes and assignments that require students to do observations, interviews, and eventually a practicum at our early childhood education campuses. There, they are paired with an experienced educator, who then has dedicated time to coach the novice teacher and help them learn to observe and engage in the ways the stories above showcase.

Even the mentorship experience for adults is mutual, co-constructed, and agentic. Through this practice of high-quality teaching, the mentor educator sees the curriculum in a new light and becomes more fluent in articulating their practices. The growing relationship between the novice teachers and the experienced teachers helps leadership more fully support the novice educator in infusing their gifts into the program. For example, we partner novice educators with veteran educators in their first two years. This fosters direct teaching, mentoring, and coaching between the two so that institutional knowledge, values, and practices are passed on to the new teacher and fresh perspectives are shared with the veteran teacher. We find this partnershipt both creates deeper “roots” in our schools and new “wings” to continually improve our work. We also have the California Mentor Program, which then allows trained and certified early childhood educators to receive a stipend for hours of coaching offered to mentees. This helps to elevate the field by also addressing compensation issues in early childhood education.

Once early childhood educators have received their credential, ongoing professional development and feedback is critical to keep the stream of learning moving and into ever-creative spaces. Unlike traditional professional development which is often prepackaged, passive learning, our ongoing development programs are tailored for staff after we learn more about who the teachers are as well as their goals for themselves. We offer school-wide professional development that fosters curiosity, collaboration, and care in the learning and teaching of young children and adults. This might even include opportunities for teachers to take workshops on materials, such as wire, clay, sewing, etc., or it might include opportunities for teachers to understand responsive classroom management, working with children with special needs, or strengthening home-school partnerships with families. It can be offsite: conferences offered by other Reggio-inspired schools, and even traveling internationally to the Bonsai Institute in Copenhagen to study the value and importance of the forest schools or the Reggio Emilia schools in Italy (funded via grants and grassroots fundraising that aligns with our core values).

Conclusion

Agency is a fundamental part of development and is crucial for thriving as adults. The Reggio approach to education, rich in decades of learning, showcases the importance of instilling agency from a young age. As educators, it is imperative that we take these findings seriously and apply them in our practices.

Investing in high quality agentic teacher training and professional development, as well as enhancing teacher compensation are critical steps toward elevating the quality of early childhood education. These initiatives not only improve the skills and knowledge of our educators but also contribute to the overall well-being of our children.

Ultimately, fostering agency in young learners not only prepares them for academic success but also for personal growth and active participation in society. As we look toward H3, our commitment to these principles will ensure that early childhood education remains a dynamic and nurturing field, responsive to the needs of both educators and students alike. Let us be proactive and innovative, continuing to invest in and celebrate the profound impact of early childhood education on our society’s youngest members.

Losmeiya Huang is the Campus Director for Growing Place Ocean Park.

This blog series is sponsored by LearnerStudio, a non-profit organization accelerating progress towards a future of learning where young people are inspired and prepared to thrive in the Age of AI – as individuals, in careers, in their communities and our democracy. Curation of this series is led by Sujata Bhatt, founder of Incubate Learning, which is focused on reconnecting humans to their love of learning and creating.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.