Framing and Designing the HOW

Key Points

-

The referenced circle graphic is intended to guide how we talk about our work as a system, internal and externally.

-

It also is about understanding our why on a personal level.

-

Learning systems are specifically designed to get the results they have, and to change results, we have to redesign the system.

After an eventful few years, many organizations are revisiting their purpose, asking the tough questions about why they exist, what is ultimately valued, and what is needed for all learners to achieve. This reflection leads to a path of change for an organization.

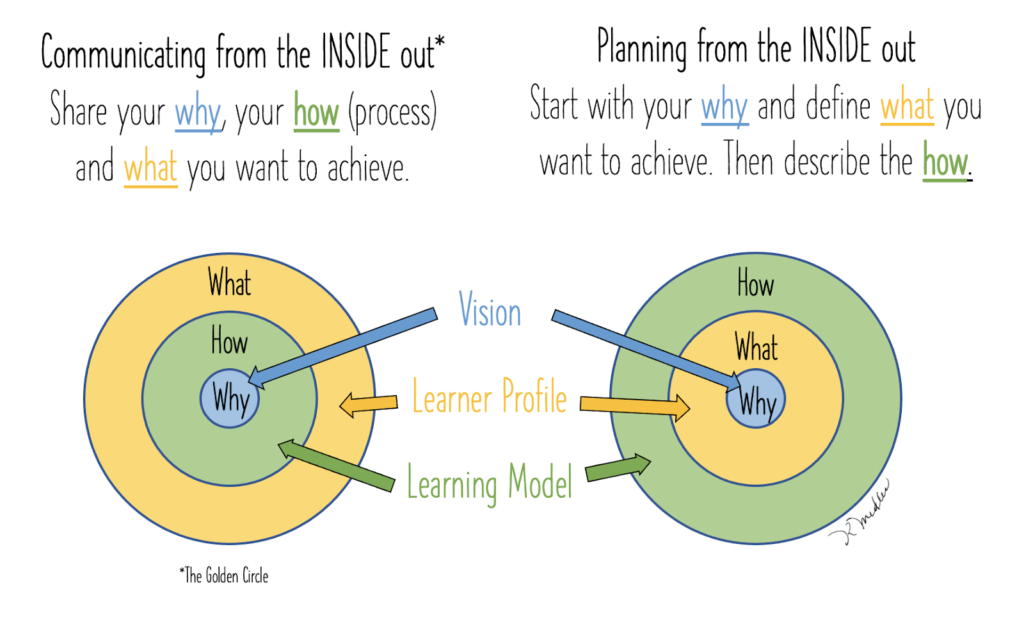

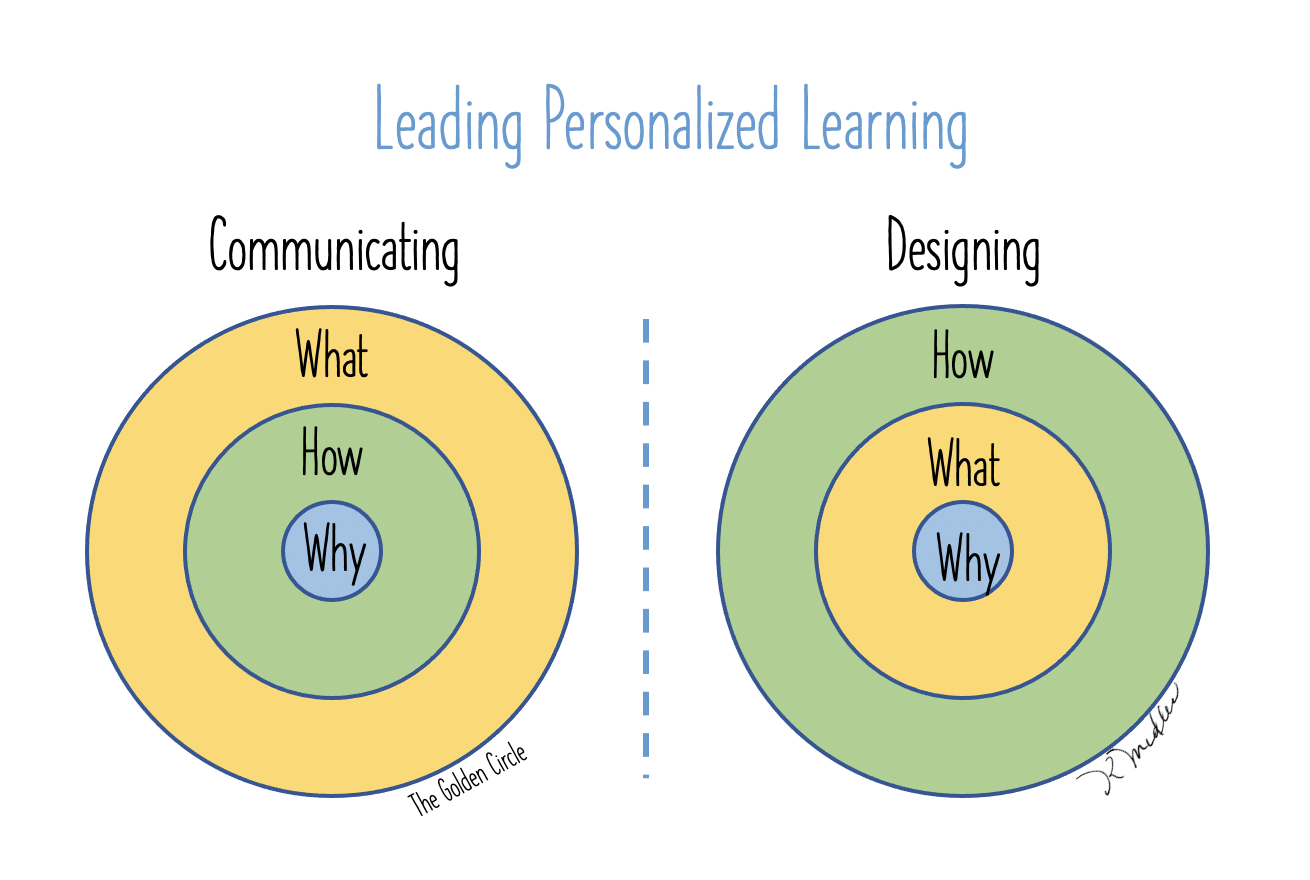

The Golden Circle of the Why, How, and What is a familiar process for organizations. Simon Sinek and others have used this framing to explain the work of alignment and coherence. The referenced circle graphic is intended to guide how we talk about our work as a system, internal and externally. It also is about understanding our why on a personal level. Using this guidance and model has been a popular approach to communicating transformational work in education.

As a learning system, however, we approach the design work in a different order. We are trained to design with a goal in mind, a learning outcome, and a learning experience. After designing the why, we move to the goals, our what, and then set our path to design the how. This process is to define how we learn, our instruction, our assessment, and how we report on growth. After defining the why of what we do, our approach flows next to the outcomes, or the what. Where we dedicate our iterative efforts resides in the how.

Defining the Why

Learning systems are specifically designed to get the results they have, and to change results, we have to redesign the system. In terms of transforming learning, it is crucial to define why a learning organization exists. This process takes time in order to equitably invite stakeholders to process and gain understanding. To intentionally bring diverse voices to the table to build and/or update the vision, and to flatten access by inviting new voices into conversations providing transparency in communication about the process and feedback collected.

Learning systems are specifically designed to get the results they have, and to change results, we have to redesign the system.

Rebecca Midles

This can take shape as a shared vision of purpose and future goals. This vision can also be refined to take a smaller-grain-size shape learning goal commonly referred to as Learner Profiles or Graduate Profiles, which often rest on a human-centered design structure or set of beliefs. Understanding the organization’s role in their community and how they serve this community is a critical starting step in the journey toward providing learner-centered and community-centered learning.

Defining the What

With a vision as a driver and a starting definition of learner profiles, organizations can move to develop an understanding of what learning could look like to support these outcomes. This can often look like an aligned set of competencies or a set of learning look-fors across the system that supports the learning vision by creating a shared understanding of expectations. It could be a set of design principles to shape future learning experiences. There may also be agreed-upon commitments between staff about how to work together to make this vision a reality for all kids. This is not a small task and requires considerable and commendable effort. It is also the beginning and doing this well is a great boost to the work ahead. This defines the why, and the what, and in the best case, it begins to define the how.

As educators, our profession lives day-to-day in the how. This is the not-so-secret sauce to personalized learning, it is the learning model that makes visions of learning a reality. We dedicate our efforts toward this iterative process in hopes of creating transparency and therefore collaboration, agency, and systemic shifts toward learning growth for all our learners.

Defining the HOW

Whether it is called a learning model or a learning framework, the way in which each member of a team supports learning and growth needs clarity and accessibility. For example, an expectation might be set that great teaching is fundamentally about relationships, which requires safety, trust, and the expectation to know our learners, their interests, and their passions. This could be tied to a guiding vision that learners deserve a space to grow, a place that has personalized high expectations and instills a belief that learners can lead their learning choices and become agents and coauthors of their learning path. There could also be a focus on learning culture, mindsets, and dispositions to prepare learners and adults in the organization for future growth and the level of change.

Without framing how the implementation will be inconsistent and may not solve inequitable experiences that most transformational visions are trying to address. In an example of co-designing an instructional framework, a school district in Colorado intentionally designed their groups in coordination with the teacher association while also including representation from leadership and board representation. Successful efforts toward implementation have provided meaningful and thoughtful ways for all teachers to share in the design. This includes continuing to collect iterative feedback after initial implementation and placing educators closest to the level of implementation directly at the heart of the process.

|

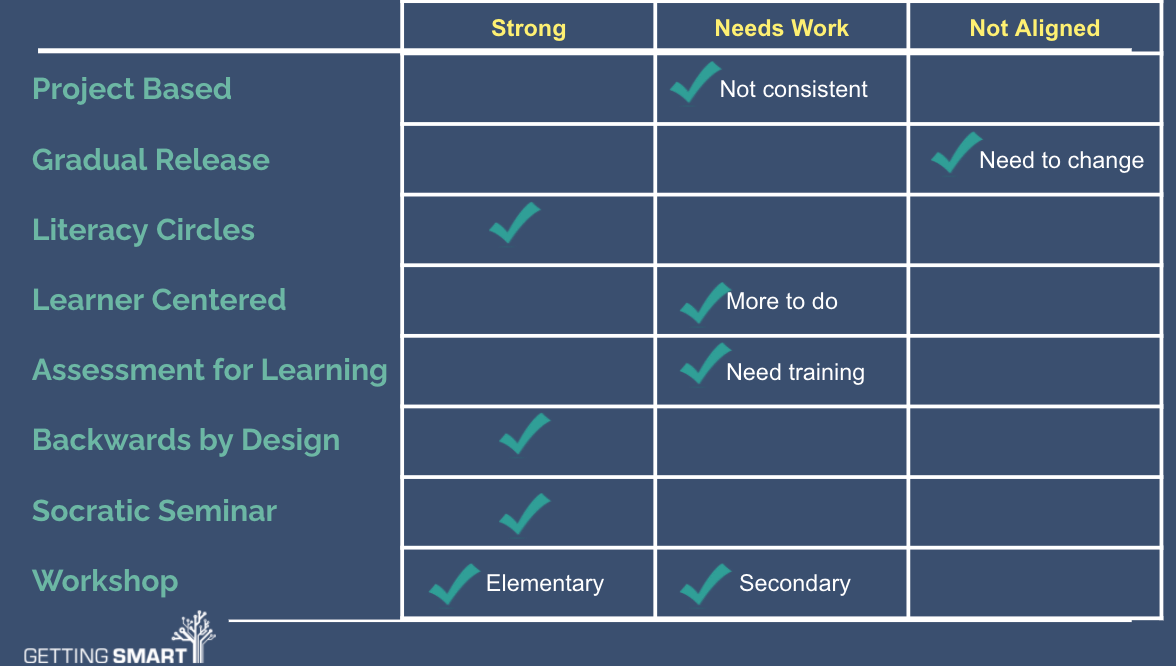

Example of reviewing programs and learning approaches toward a vision of learning |

|

Designing the Learning Model through an instructional framework directs a system to look at what is currently in place (programs, instructional approaches, and assessment protocols) and then identify the gaps and needs. Listing all of these items and assessing where an organization is will also determine the professional learning that is needed and where to start. Adult learning and capacity building become aligned with the level of change and coordinating approaches to leadership and feedback cycles.

Systemic Change

Transforming a learning organization takes time and the route matters. Although certainly worth the effort and the resources, it also requires a collaborative leadership approach, one that ensures representation and a commitment for all learners. Traditionally our schools were not designed for all learners to grow, although intended to provide families access to viable economic pathways, it was not intentionally designed for all, it was designed to be efficient. It was designed to educate the future workforce and to sort the prevailing culture’s view of college-ready.

Human-centric structures are not a prescriptive recipe, it does not involve a canned curriculum with a paced delivery, and it certainly does not assume that all 15-year-olds are ready for the same learning on the same day. Moving out of this paradigm requires brave leadership, not simple management.

To have brave conversations, we have to visit that understanding and admit that our schools have not dramatically changed. We need to closely examine the structures in our learning organizations and how these were designed for the ease of adults to manage the system. The Carnegie Foundation, a leader in the field of improvement science, offers tools and resources for how to lead change. Co-designing Schools Toolkit provides resources for equitable change at the school level.

Questions to Consider:

- What is the purpose of your learning community? Why is it important?

- Why does the current learning system need to change?

- Who are the stakeholders and how to ensure all voices are heard?

- What is aligned to your vision and working well in your learning system?

- What will graduates need when they leave your system? (Graduate Profile/Learning Profile)

- What practices need to be replaced? Improved?

- What is your learning data sharing? What is it not sharing?

- How will structures around learning need to change?

- How will graduates have agency in the learning process and their goals?

- How will learners, educators, and families engage in this design?

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.