Building Trust through Design Thinking

By: Sabba Quidwai and Devin Vodicka

In part one of our series we talked about the relationship between the importance of educators collaborating to design learning experiences. When designing collaborative environments where everyone thrives, developing relational trust is incredibly important as this work cannot be and should not be done alone. As was found in a comprehensive, multi-year research partnership with the University of California San Diego, improvements in the levels of trust were predictive of positive changes in many other important areas. In fact, “students’ trust in their educators (principal and teacher trust) has the highest average association with all areas that together make up the student’s school experience.”

A similar phenomenon was found when analyzing the level of trust that teachers had for their principals, where principal trust was found to have the highest overall association with areas that together make up the teacher’s daily experiences in their work, including collaboration between teachers, communication with parents, instructional practices, and equity beliefs.

What is trust? While there are many different definitions, we feel that it is important to ground our efforts on the work of Bryk and Schneider who conducted extensive research on relational trust. In their studies, they found that schools with high levels of relational trust were three times more likely to improve in academic achievement and those schools with low levels of relational trust showed little or no improvements.

Relational trust grows or decreases as a result of the interactions between two individuals. It is important to recognize that relational trust is dynamic (meaning that it changes over time) and it is specific to particular contexts and tasks. In short, while there is a tendency to generalize trust between people, the reality is that we trust one another to do specific things under specific conditions. As an example, a teacher may trust a colleague to co-plan an instructional unit but that does not mean that the teacher would trust the same colleague to co-host the school talent show. In addition, levels of trust are influenced by each person’s unique history and perspective.

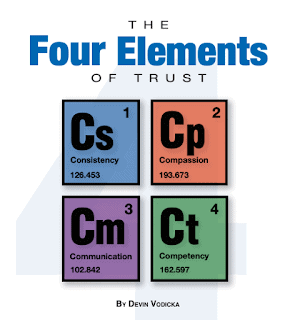

Given the reality that relational trust is dynamic, contextual, and dependent on others, it is not possible to unilaterally improve trust. While building trust is complex, research does indicate that there are critical components that help to build (or erode) relational trust. We suggest that educators should be mindful of the “Four Elements of Trust” and intentional in their approach. The Four Elements are consistency, compassion, competence, and communication.

Recent research by Quidwai found a critical connection between relational trust, collaboration, and the development of mindsets and skillsets when engaging in design thinking through her doctoral study of Design 39 Campus in Poway, CA. Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process to complex challenges which seeks to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems and create innovative solutions to prototype and test. (Interaction Design Foundation, 2020). Building a culture of empathy is the first step towards building a foundation of trust to foster social relationships and establishing shared norms and values within the organization (Edmonson, 1999). Amongst educators in particular, this leads to a culture of knowledge exchange, sharing of best practices and collaboration on lessons that have a direct impact on stronger learning outcomes for students (Moolenaar & Sleegers, 2010).

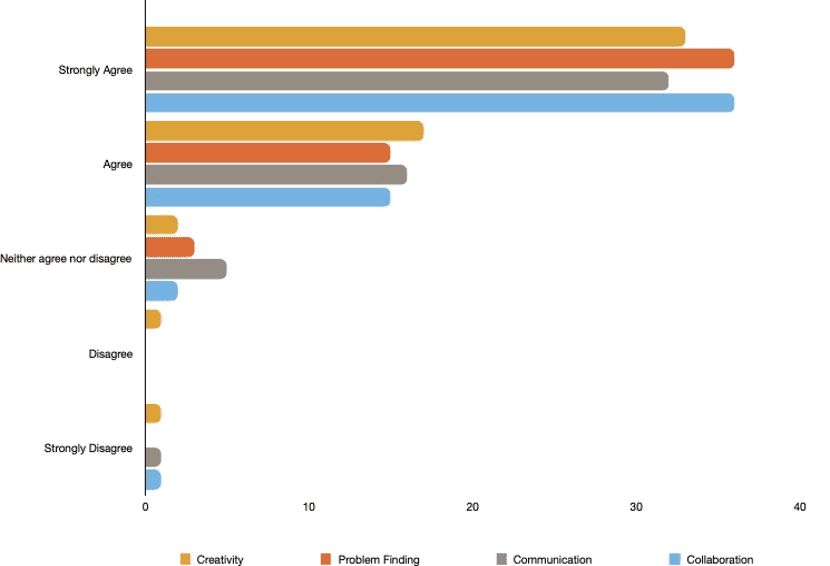

When surveyed, over 90% of the Learning Experience Designers (LEDs) see the value of integrating design thinking into the curriculum to develop the skills of creativity, problem finding, collaboration, and communication:

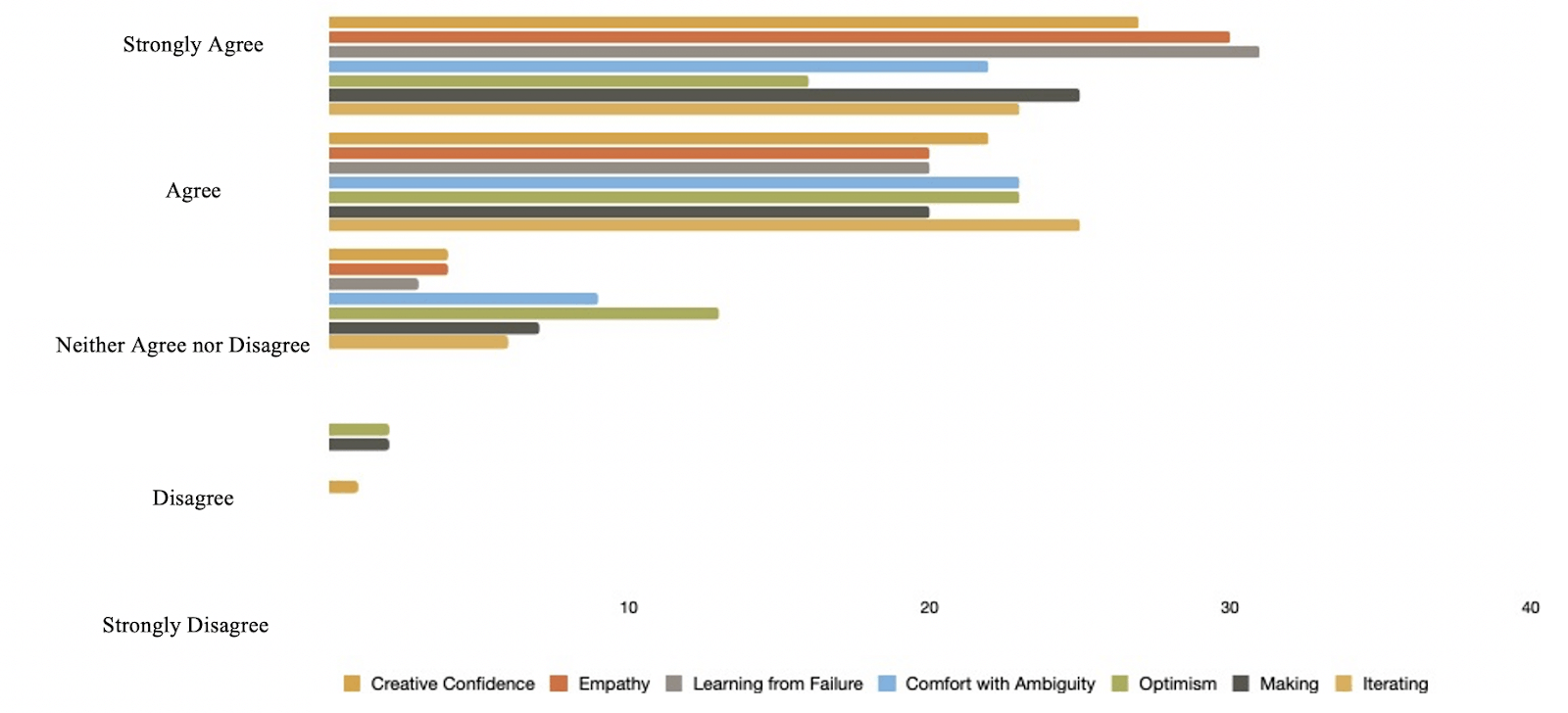

In addition the survey results indicated that creative confidence, empathy and learning from failure were seen as the strongest mindsets being developed, followed by iterating, making, comfort with ambiguity and then optimism

The performance improvement the LEDs see in the skills and mindsets their learners are mastering deepens their trust and collaborative work with one another when they each bring their “superpower” to the table. Establishing that everyone has a unique superpower, a strength that they bring to the table was a foundational element of collaboration. The topic of superpowers came up in all the interviews and as one LED shared, “we are capable of all things and if we had to do them we could, but our superpowers highlight what we are energized by and what brings us joy. It allows us to develop a deeper sense of empathy with one another because we understand that ok in collaboration you need this, I may not need that but by knowing this about each other we can help give each other what we need.”

Building off of these research insights, this article will provide framing for each of the four elements of trust along with suggested design protocols for educators.

Consistency & Competence

When we are in a relationship with others, there is a degree of vulnerability that is inherent in every interaction. As a result, we typically feel more safe in taking risks if we believe that we can rely on the other person. This is why definitions of trust often include predictability, reliability, and integrity. Being able to “count on” the other party is an essential element of relational trust.

Educators can model consistency by maintaining their commitments, adhering to routines, and implementing systems and procedures which build comfort and security. As one LED shared, “team here and collaboration does not mean we are being best friends it means can I trust you to show up and do your best.”

Getting things done well is a critical element of relational trust. It isn’t just what we say, but what we do that influences the level of trust throughout our interactions. Follow through on commitments is essential. In addition, we need to remember that being trusted with certain tasks (usually based on past performance) does not automatically mean that we are trusted with all things. Educators can model competence by achieving goals and celebrating successes.

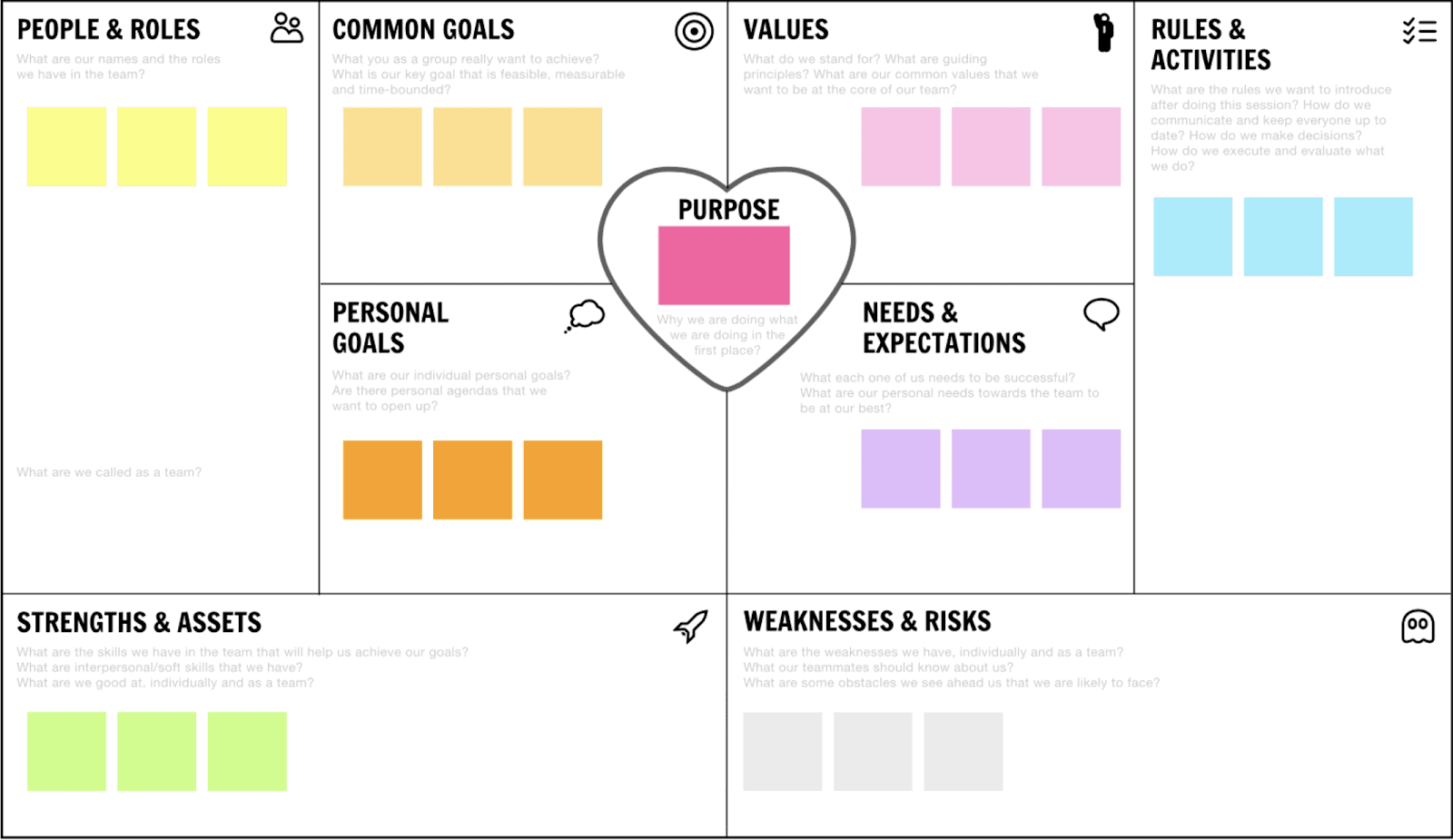

One way to utilize a design approach to establishing consistency and competence is through the Team Canvas model.

Credit: Team Canvas. Click to launch a digital version you can use with your team

Compassion & Communication

Relational trust is more likely to exist when we feel cared about and connected to the other person. This occurs through meaningful interactions where we feel a sense of empathy and concern. Importantly, the research in this area shows that the care must be sincere and genuine. Expressions of compassion often include making exceptions and therefore an inherent tension exists between compassion and consistency. Educators can model compassion by taking time to learn about student strengths, interests, and passions and then adjusting and co-creating plans.

Communication is the exchange of information that conveys consistency, compassion, and competence. In other words, this can be an amplifier or a muffler for the first three elements of trust. The research here is also clear that receptive communication – how we receive information, particularly through listening during synchronous interactions – is more important than our expressive communications. Educators can model communication through active listening, soliciting input and feedback, and by clearly expressing their ideas. Maintaining confidentiality is also vital to maintaining trust.

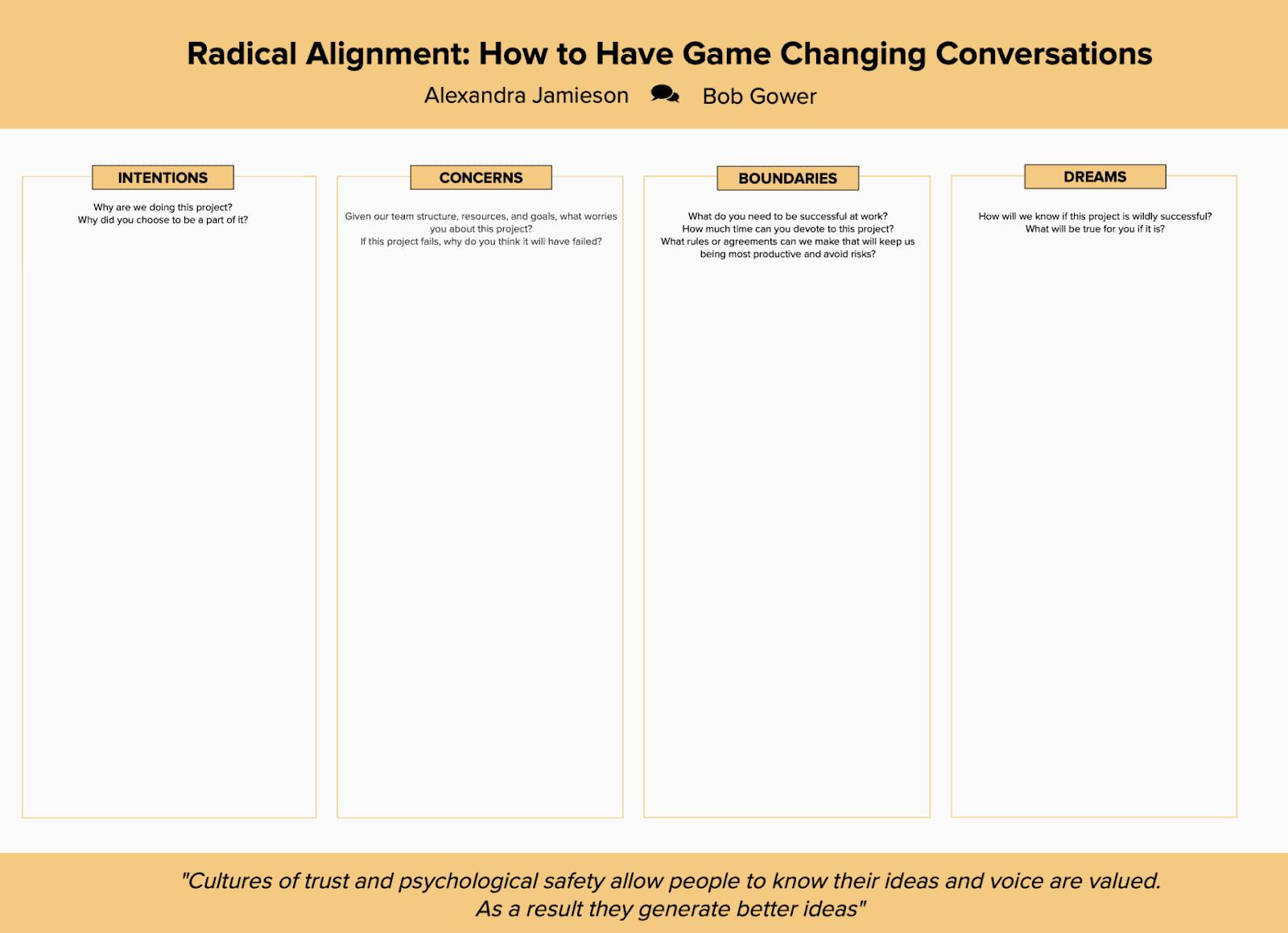

One way to utilize a design approach to establishing compassion and communication is through the All In Method by Alexander Jamieson and Bob Gower from their book, “Radical Alignment: How to Have Game Changing Coversations That Will Transform Your Business and Life.” In this method each team member shares their intentions, concerns, boundaries and dreams.

Click to launch a digital version of the above template that you can use with your team.

The four elements of trust are essential to create and sustain strong relationships. They are multi-dimensional and exist in tension to one another. Consistency, for example, is “intrapersonal” and internal while compassion is “interpersonal” and external. Competence and communication exist between dyads (two people) but also at the levels of organizations, communities, and networks. Emphasizing consistency often comes at the expense of compassion while competence and communication require time that is often at a premium. In other words, developing relational trust is hard work. And while it may be difficult, we know that relational trust forms the foundation for meaningful collaboration which is imperative for ongoing growth and transformation.

Connecting the abstract concepts of relational trust with the protocols and practices that we have suggested is done to provide concrete suggestions that can be done anywhere and at any time. As we have seen from innovative exemplar schools such as Design 39, the possibility for transcendent learning environments that create a “new grammar of schooling” is real and achievable. In the words of the educators at Design 39, it is also an ongoing process

One LED shared, “There is so much trust. We aren’t afraid to have a big idea because you have people who will help you take that idea, make it better and make it happen.”

Design39 is not a place where educators wait to be told what to do and when to learn. Rather, the culture at Design39 encourages and trusts the LEDs to personalize their learning and development as professionals, to seek out the resources and experiences that will enhance and develop their ability to define and design a new grammar of school and supports the LEDs by providing the time and space to dream, share and execute on their ideas. Seeing the radical transformation in their own teaching practice as LEDs, and witnessing their learner’s creativity, problem solving, communication and other trending skills and mindsets develop, increases the value for the ongoing integration of design thinking. At the heart of this process is a foundation of trust, rooted in consistency, compassion, competence, and communication.

Additional References

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

- Gower, B. & Jamieson, A. (2020). Radical alignment: How to have game changing conversations that will transform your business and life. Sounds True.

- Moolenaar, Nienke & Sleegers, Peter. (2010). Social networks, trust, and innovation. How social relationships support trust and innovative climates in Dutch Schools. Social Network Theory and Educational Change. 97-114.

- Quidwai, S. (2020). Defining and designing a new grammar of school with design thinking: A promising practice study. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Southern California

- Vodicka, D. (2006). The Four Elements of Trust. Principal Leadership, 7(3), 27-30.

- Vodicka, D. (2007). Social capital in schools: Teacher trust for school principals and the social networks of teachers. Doctoral Dissertation, Pepperdine University

For more, see:

- “I Could Never Do This Alone” – Collaboration, Trust, and Human-Centered Design at Design39

- Redesigning School: Six Key Pillars From Six of the Most Innovative Schools and Programs

- Time to Redesign is NOW

Dr. Sabba Quidwai is a social scientist, graduate of the Global Executive EdD program at the University of Southern California and a former high school Social Science teacher. Follow her on Twitter at @askMsQ.

Devin Vodicka, Ed.D, is the Chief Impact Officer at Altitude Learning, author of Learner-Centered Leadership, and former superintendent of Vista Unified School District in San Diego, CA. Follow him on Twitter at @dvodicka.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.