Designing Schools for Shared Use: A Pandemic Silver Lining

By: Randy Fielding, Cierra Mantz, and Nathan Strenge

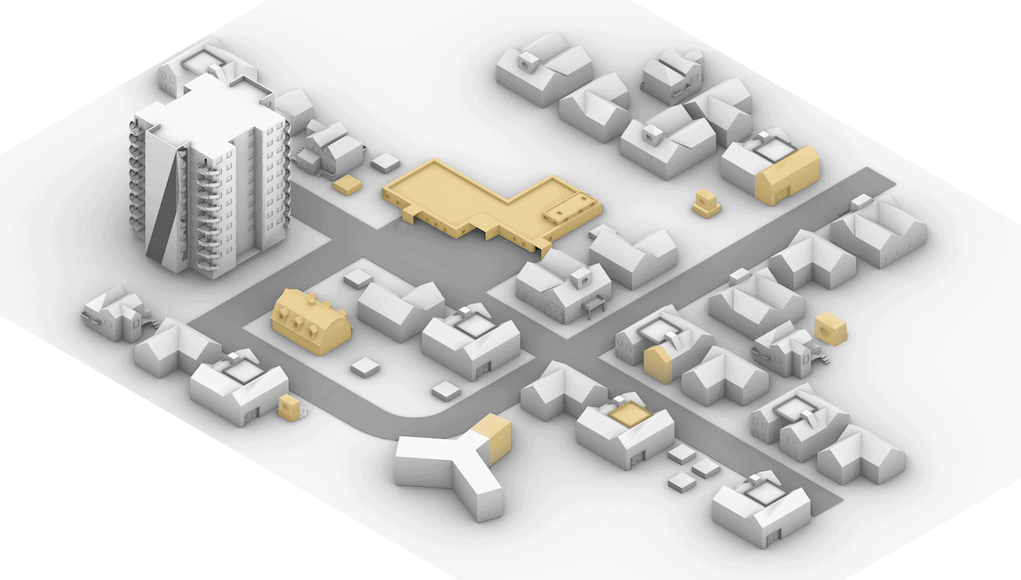

Note: The above illustration was originally created as part of a series of design patterns Fielding International (FI) created in response to the challenges faced by schools as a result of COVID-19. Click here for the full publication.

More than ever, flexible, multi-use school buildings are essential for the future of education. The value of sharing facilities between schools, universities, community organizations, businesses, and public recreation organizations has been championed for years, but has failed to take hold in a significant way because of the complexity of governing and financing shared use facilities. That’s about to change due to health, economic, and educational forces that are gaining momentum and making imminent change necessary.

Forces Driving Toward Shared Facilities

The first force that is driving us towards shared facilities is the demand to upgrade heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This force is particularly challenging due to currents already in motion, pushing construction costs increasingly higher. According to the Second Quarter 2020 North America Quarterly Construction Cost Report by Rider Levett Bucknall, the average cost of construction in North America has linearly increased by nearly 27% in the past five years. Considering this steady increase, the fact that the cost of construction is nearing $600/square foot for school facilities in some major metropolitan areas, and the complexity of COVID response ventilation, renovation is becoming increasingly less viable; it’s often more economical to tear down an older building than make all the required upgrades. From the perspective of achieving effective shared uses facilities, designing a school from scratch creates an ideal context for intentionally incorporating designated spaces for multiple enterprises and designing with use synergies in mind. (More on holistic strategies for COVID responsive design)

The second force that is driving us towards shared facilities is a national and global shift from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism. Milton Friedman’s 1960s economic philosophy that the only role of business is to deliver profit to shareholders is rapidly evolving to an acknowledgement that business needs to serve shareholders as well as customers, employees, communities, and the planet. As stated by Martin Lipton, senior partner at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, in a September 2020 New York Times article, the shift is illustrated by The World Economic Forum’s adoption of The New Paradigm in 2016 and, in 2020, the publication of the Davos Manifesto which embraces stakeholder and E.S.G. (environment, social, and governance) principles.

As a result of this paradigm shift, there is an increasing appetite across all markets for more holistic thinking that acknowledges the benefit of reorienting decision making to include the ‘greater good’ and social responsibility in the fiscal calculus of a business. In this new economic environment, schools and school districts are poised to leverage their position as a public benefit enterprise to partner with businesses and organizations that are embracing this new philosophy. (More on shareholder vs. stakeholder capitalism)

The third force that is driving us towards shared facilities is a growing awareness in the educational world that the most effective learning is tied to purpose—to solving real-world problems. Problems such as racial equity, food and housing insecurity, health care, mental health, substance abuse, and the sustainable use of resources are rarely solved by focusing on a single discipline. Real problems and solutions are inherently interdisciplinary. This can be seen clearly in the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 17 goals that span numerous disciplines that are necessary to create a more sustainable world. Informed by the intrinsic complexity and interconnectedness of today’s problems, the OECD emphasizes interdisciplinary knowledge as an important aspect of the future of education in its long-term initiative, OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030.

Schools as stand alone entities may be easier to govern but they are not well suited to solve complex, real-world problems. Integrating school programs with community organizations, businesses, universities, and public recreation organizations offers the synergy needed for world-class learning. Shared use facilities more easily facilitate a cross pollination of ideas through shared programming and expose students to businesses and organizations already working to address pressing local, national, and global problems.

Barrier to Achieving Shared Use Facilities

With these driving forces nudging us ever closer to realizing the vision of shared use facilities, the pressing question then becomes: How can schools, businesses, and community organizations work together to finance and govern shared facilities? In, It’s Time to Separate Facilities From Operations, Tom Vander Ark, author of Smart Cities, The Power of Place, and the cofounder of Getting Smart, describes the problems with the current way of provisioning facilities, including a lack of equity, a lack of maintenance, a misalignment with technology investments and bond funding, and a lack of portfolio management. He also proposes three different options to shift funding structures that support shared facilities. These options include moving facilities into a public trust, providing states fixed asset funding, and performance contracts for operators.

Clearly, there are ways to address financial barriers that, in the past, may have prevented the successful implementation of shared use facilities. Yet, even with financial issues addressed, there is still the issue of governance. Through a concerted effort to negotiate the varied interest of numerous stakeholders, it is possible to establish the appropriate legal governance structures and develop requisite management systems, policies and procedures, and communication strategies to effectively maintain operations. (More on governing and the operational management of shared use facilities)

The Silver Lining

In the annals of history, the COVID-19 pandemic will be recognized as a moment of marked upheaval and significant societal change. The pandemic has created an opportunity for a collective reevaluation of deep-seated structural issues, philosophical inconsistencies, and social inequities throughout our society. We can no longer complacently settle for the way things have always been done. Breaking the norm of single-use school facilities is one of those opportunities. By capitalizing on the health, economic, and educational forces present at this momentous juncture, now is the time to renew efforts to create and maintain shared use facilities.

Stories from the Field

The following examples illustrate the challenges, successes, and benefits encountered by a charter school, a large school district, and a private school that have successfully established and maintained the shared use of their facilities.

1. Public-Private Interdependence. High School for Recording Arts (HSRA) is a 350 student charter high school in St. Paul, Minnesota that was established through a public-private partnership between the school, a 501(c)3 nonprofit, and Studio 4 Enterprises, a for-profit music recording and production studio. The vision for HSRA came from the lived experience of David “T.C.” Ellis who observed countless youth within his community who were passionate about music and spent time at this professional recording studio but who were also at significant risk of dropping out of school due to boredom and being disenfranchised by an educational system that didn’t value their unique talents and passions. Ellis saw an opportunity to use music and the recording arts as a way to completely transform the high school experience for young people in his community by leveraging students’ passion, resourcefulness, and talent to create a truly personalized, contextual learning environment.

In order to do this, Ellis envisioned professional recording studios—the for-profit business he had already established—embedded in the structure and daily life of the school. This bold idea would have implications on multiple levels including: the business structure, operational practices, and the design and use of the facilities. Cautious reticence on the part of Ellis’s long-time friend, colleague, and Executive Director of HSRA, Tony Simmons, soon gave way to the search for a creative solution to make this dream a reality. Tony’s research revealed that it was common practice for nonprofits to form for-profit companies as a way to get around the operational restrictions placed on nonprofit organizations. After vetting the details with a leading national attorney who specialized in nonprofits, they formalized the business structure plans. Since the for-profit company already existed, their approach simply inverted this common practice and married Studio 4 Enterprises, with the nonprofit behind HSRA.

Ellis put it succinctly, “If you have the right stewardship and the right balance it’s an amazing marriage. [The two profit structures] can really work together.” Having both entities working in tandem provides the necessary flexibility for the organization to thrive and grow in truly strategic ways. Since receiving its charter in 1998, HSRA has experienced remarkable success, due in part to the creative agility enabled by the partnership structure between Studio 4 Enterprises and HSRA.

The most recent example of this is an initiative that arose from a need they saw among their students. For many, the conventional trajectory of attending a 4-year college isn’t the right fit, yet they still needed additional time and support to help them find their way in the current economy. Essentially, these students needed a fifth year, but charter law doesn’t allow this. As a result, Studio 4 Enterprises, which has evolved to include educational services and management as a part of their business model, was able to step-in and invest the time, energy, and money to launch the program while working as a contractor for HSRA. Now, all three organizations—HSRA, Studio 4 Enterprises, and Diverse Media Institute (DMI, an independent nonprofit licensed by the Minnesota Office of Higher Education)—are all housed in HSRA’s 35,000 SF building, a facility intentionally designed for the study and production of audio and other media. Furthermore, building upon the operational synergy of these organizations, plans are currently underway to build an impact hub and supportive housing facility on the current HSRA campus with the goal of expanding the breadth of the value they bring to their community and further serve the needs of youth.

2. Partnerships that Stand the Test of Time. Hopkins Public Schools (HPS) is a public school district in Minnesota that serves an amalgam of first-ring suburbs of Minneapolis, namely Hopkins, Minnetonka, Golden Valley, Eden Prairie, Edina, Plymouth, and St. Louis Park. Long embedded in the district’s operational philosophy is an approach for facilities sharing with municipal partners and compatible, outside organizations. Hopkins approaches shared facilities using four primary strategies: (1) a partnership structure whereby multiple entities collaborative lease and operate a shared facility, (2) leasing spaces within their facilities to outside organizations, (3) leasing commercial real estate from outside organizations and municipalities, and (4) renting space within their facilities for short-term events. To understand Hopkin’s successful history of sharing facilities, we spoke with Dre Johnson, Coordinator for District Facility Use, and Alex Fisher, Director of Community Education and Engagement. This conversation illuminated the practices they maintain to ensure that their approach to facilities operations provides maximum benefit to students and the community alike while hedging common challenges that arrive with the shared governance of facilities.

Notable among the shared-used relationships maintained by HPS are the Lindbergh Center and The Depot Coffeehouse & Performance Venue. The Lindbergh Center is a 92,000 SF state-of-the-art fitness center on the campus of Hopkins High School. It is operated through a partnership between the City of Minnetonka and HPS with each entity covering 29% and 71% of operating cost, respectively. The center is synchronistically used by student groups and the community on a daily basis with community members accessing the space from 6am to 9pm and students using the facility for phy-ed classes, special ed classes, and sports training and events during and outside of school hours. This partnership has seen twenty-five years of success, and there’s no reason to believe that will change anytime soon.

Similarly, The Depot Coffeehouse & Performance Venue is a partnership among the City of Hopkins, the City of Minnetonka, HPS, and Three Rivers Parks District (a special park district serving multiple counties in and beyond Twin Cities with the mission of promoting environmental stewardship through recreation and education in a natural resource-based park system). The Depot was created in 1998 as a youth initiated project to give students a positive, supportive environment to learn, relax, have fun, and develop life and work-place skills. Contributing to this mission, the attached performance venue specializes in providing a literal and metaphorical platform to elevate young artists within the community.

While the City of Hopkins is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the coffee house as well as the management of the performance venue, all four partners contribute to the lease in order to use the space. For HPS, it serves as a living classroom for high school students, where they can learn barista and other life skills. The school district can access to the space with a phone call notifying the onsite manager of the desire to use the space for classroom purposes; however, according to Fisher, it’s mainly used “to engage youth and others on the artistic side who want more of a chance to express themselves and for after school and evening programming.” Recently, it’s been used for spoken word poetry and music events as part of the community education programs, but there’s great potential to rekindle the original concept and incorporate more classroom functions and expand learning opportunities.

From an operational standpoint, Dre Johnson, Coordinator for District Facility Use at HPS, was clear that the success of both of these ventures hinge on several factors, top among them, communication. When it comes to communication Johnson noted that when possible and appropriate, it’s important to involve partner organizations in the decision making process, but that’s not always prudent. In that case, at a minimum, it’s vital to make sure all parties involved understand why decisions have been made. According to Johnson, “even just explaining the choices that have been made can go a long way in making sure everyone feels included in the process.” Another key factor contributing to the successful operation of the Lindbergh Center and The Depot is the ability to maintain a relationship of trust. Each partner needs to feel valued in the relationship to create a baseline level of trust and stability. This means respecting clearly defined, jointly negotiated boundaries and balancing the roles of each partner while being open and honest about priorities and adjustments that need to be made. Alex Fisher, Director of Community Education and Engagement, added that this includes, “ensuring lease agreements clearly specify the use intent and boundaries for each party. Each time a lease renewal occurs it’s an opportunity to reevaluate the relationship and the terms of the agreement to make sure there’s an alignment in the relationship.”

For Hopkins it has been helpful that their assistant superintendent, Nik Lightfoot, is also a lawyer who has a keen eye and the bandwidth to review and vet their legal agreements. However, no agreement is capable of covering every issue that could possibly arise, so Johnson acknowledged that it’s advisable to, “Plan for the unexpected in your agreements. Make sure there’s as little ambiguity as possible because that makes it easy to settle any disputes. Have a dispute resolution strategy in place and make sure that when there is a conflict or a convergence of need, there [are] guidelines to follow saying, this is the way things are done and we’re going to follow that, then nobody has an opportunity to be upset.”

Operational challenges aside, it’s clear that from Hopkins’ experience that the district, its students, and the broader community benefit considerably from sharing facilities with outside organizations, municipalities, and businesses. According to Johnson, access and exposure to resources and opportunities made available through their partnerships is extremely valuable for their students. The district’s partnership with the local arts center and the Lindbergh fitness center are crucial for families that don’t have the ability to pay for private facilities. Access to these places can broaden students horizons and, in the case of the fitness center, provide them with a resource that can help them change their lifestyle.

At the community level, the shared spaces and programming is a way to include and welcome students’ families into the district and forge bonds that wouldn’t otherwise exist. Because the district draws students from seven different cities, there aren’t the same long-term or close-knit relationships that may exist in other smaller districts that draw their student populations from a single, unified community. As Johnson put it, “There are so many challenges in everyday life, that communication and shared experiences can help break down some of the walls and barriers and you do that by having spaces in your community that people feel comfortable going.” By sharing their facilities and partnering with outside programs, HPS draws people into their buildings and makes them comfortable there, which in turn helps the students by making them more invested in their academic experience. As Johnson said, “It changes your whole dynamic when you feel that connection and when you see your district partnering with local businesses.”

Relatedly, Hopkins is experiencing white flight. But this exodus is not inevitable. By providing facilities and programming where people and families can interact, form bonds, and feel like a part of the same group, the district has been able to break down some of the barriers that would have otherwise divided the community and hastened the departure of white families. As Johnson explained, community events and community education programs provide “a huge opportunity for us to dispel some of that fear that you’re getting less of an experience being in Hopkins vs. our neighbor to the west.”

Furthermore, considering the white supremacy and structural racism built into the public education system, Fisher noted that their partners are increasingly vital to helping the district level the playing field as they seek to provide greater equity for their students. By partnering with organizations that work outside the institutional confines that are system entrenched in patterns of structural racism, the district can ensure their students have access to resources and services that the district alone doesn’t have the knowledge, bandwidth, or expertise to provide internally.

3. Creative Funding + Mutual Benefit = Operational Sustainability. The Neighborhood Academy is a private college preparatory school serving underserved students in Pittsburgh, PA from grades 6-12. With the mission “to break the cycle of generational poverty by empowering youth and preparing them for college and citizenship,” the school only charges a modest tuition, around $50 per month. Given that the actual cost to educate each student is roughly $25,000 per year, the school was living purely off fundraising to make up the deficit at the time they engaged with Equity Schools, a benefit corporation based in Chicago that works nationally to solve capital and operational funding problems for schools founded by Richard Murray. At the time of initial engagement, the school’s big dream was to have their own gymnasium, but considering the extent of the donor fatigue they had already observed in fundraising for their operational needs, it was highly unlikely they would be able to fund this through a capital campaign.

Following Equity School’s out-of-the-box process, they didn’t accept the limitations and barriers identified by the school. Instead, from the first day they worked to get the Neighborhood Academy educators to think beyond the constraints to what truly matters, namely their dreams for the students, families, staff, and community. They helped them move beyond their ‘wish list’ of specific spaces, forget about the money, and dig down to the root of what they were trying to achieve. As Murray put it, “In effect, we erased the perceived starting line and moved it back before all the usual assumptions about square footage and dollars are applied.” By moving the starting line backwards, in this case, they were able to create an executable vision that was bigger than the educators thought possible. Instead of merely helping to raise the funds to build a gymnasium, Richard and his team proposed building a brand-new school building complete with a gymnasium and indoor soccer field as well as the establishment of an endowment for the school.

A key feature that made the project viable was the addition of the indoor soccer field. Through observations, conversations, and research Murry came to realize that there were no indoor soccer fields within Pittsburgh city limits yet the demand for such facilities was quite high, with many families traveling to local suburbs to utilize these facilities. At the same time, the residents of Pittsburgh tend to hold great pride in their city and prefer to patronize local businesses and venues. As such, adding an in-demand indoor soccer field to the design of the school provided a potential revenue stream that made the balance sheet enticing to investors and donors alike.

In the end, with the visionary design, the school was able to secure tax-exempt bonds combined with a portion of fundraised monies to build the new facilities. Because the bond financing contributed to a significant portion of the overall building costs, the school was able to aportion a significant amount of their fundraised money to form an endowment for the school. At the time of the ribbon cutting ceremony, the Neighborhood Academy was proudly able to announce both the opening of their new facility as well as the formation of a multimillion dollar endowment.

By strategically designing shared-use into the facility, the school got an elite facility that prestigious college prep schools in the area don’t even have and on the evenings and weekends, after students have gone home, the facility is open to the public, providing a much needed community asset. The icing on the cake…the profit from the soccer field is able to pay for 100% of the debt service for the bonds and the utilities and maintenance for the whole campus, freeing up significant money for other operational expenses.

Key Takeaways

- Mutually Reinforcing Values – In order to be successful, the shared-use component or organization has to be compatible with the mission and vision of the school.

- Cost-Benefit Balance – Cost conditions often make new construction more feasible than renovating old buildings, creating opportunities for purpose-built shared-use facilities.

- Legal Linchpins – Lease terms and operational agreements need to be clear so each person/organization knows their roles, responsibilities, and obligations.

- Talk it Out – Open communication and strong relationships among all parties are crucial for successful, sustainable operations.

- Knowable Unknowns – The one thing that’s certain is that issues are bound to arise. As such, it’s prudent to incorporate dispute resolution terms in legal agreements to plan for unforeseen challenges among the parties involved.

- Two-Way Benefits – Compatible shared-uses are mutually beneficial for students & the community. If done well, sharing provides access to resources and facilitates exposure to experiences and opportunities that wouldn’t otherwise exist.

- Make the Dollars Make Sense – When executed well, sharing makes financial sense! Instead of considering the financial complexity of shared-use facilities as a barrier, with the right structure, it can actually be a benefit that contributes to the financial sustainability of the school.

For more, see:

- Learning Environments for the Future: 4 Tips from Randy Fielding

- Podcast: Randy Fielding on Learning Environments for the Future

Founding Partner at Fielding International, Randy Fielding has been creating environments where learners thrive for several decades, winning prestigious school design awards along the way. Randy’s work is grounded in research, which he has shared globally in more than 30 publications and as the co-author of The Language of School Design: Design Patterns for 21st Century Learning, now in its third edition. Follow Randy on Twitter at @randyfielding.

Senior Designer at Fielding International, Cierra Mantz is a registered architect with a Masters in Educational Leadership and Societal Change. Through her work, she seeks to champion change within education through innovative design, research, and grassroots community engagement.

Senior Learning Designer at Fielding International and USA Country Lead at HundrED, Nathan Strenge approaches school design with an innovative educator lens. As a teacher of ten years, Nathan’s drive to transform education comes from his belief that all people deserve to learn in an environment that adapts to their unique gifts and needs. Follow Nathan on Twitter at @nathanstrenge.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.