It’s Time to Reassess Our Understanding of the 4Cs

The George Floyd tragedy has forced upon many of us a need to reflect on systemic racism in education. My musings have focused less on structures and policy and more on student outcomes and instructional practices.

I have for months been examining my entrenched beliefs about project-based learning, formed primarily while working at the Buck Institute for Education as Senior Director. But the furor over Floyd’s death has also forced me to examine my beliefs about 21st century skills established during my tenure at the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, where I worked for nearly three years as CEO.

The first flash of insight relates to the cultural influences on the teaching and assessing of 21st century skills, primarily the 4Cs (creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication). I really should have known better. My wife, an immigrant who didn’t speak any English when she moved here as a youngster, provides me with a daily example of how culture impacts critical thinking.

My wife is brilliant, and this can be proven objectively. She is a hospital executive but used to work as a microbiologist performing cardiovascular research in a San Francisco lab. Several decades ago she trained a young PhD student in lab practices, and he still credits her for much of what he knows about lab work. Oh, by the way, he later won a Nobel Prize for his work with pluripotent stem cells.

Despite her rigorous scientific thinking she is capable of keeping in her head what I, in my Western brain, think of as two mutually exclusive conceptual frameworks. I would be hobbled by cognitive dissonance were I to try the same.

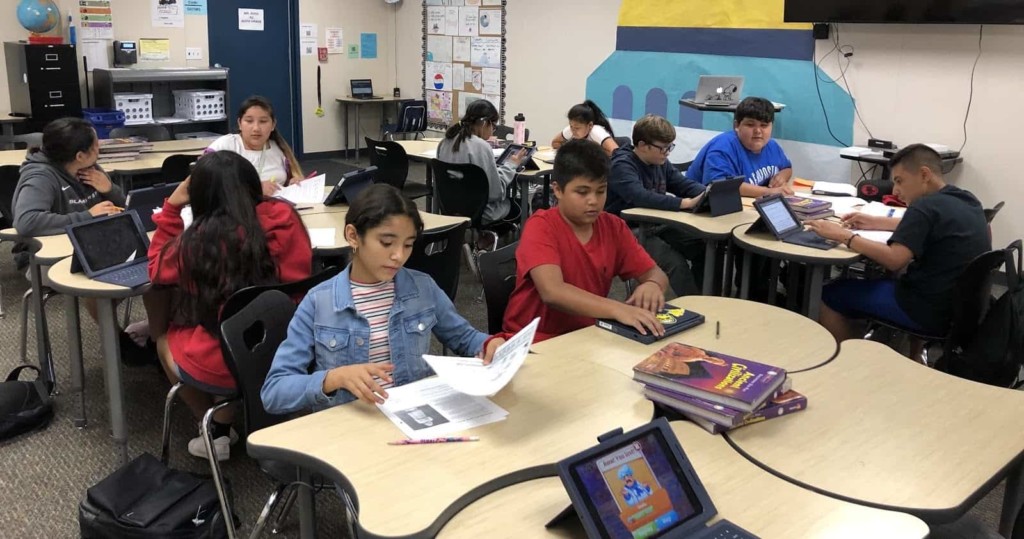

I wonder how I would have taught my wife, who is not all that different from the students I have mentored in my 11 years as a K-12 teacher. My current classroom is dominated by Latinx students (90 percent) but I have over the years taught students from Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. Surely, they too demonstrated cultural influences over their ability to create, communicate, collaborate, and critically think?

Communication

The performative features of communication are paramount in project-based learning. That’s why most communication rubrics in PBL settings focus on oral presentations. The influence of culture on students’ ability to score highly on a presentation rubric should be obvious but most of us ignore these influences. Our current metrics don’t help.

I have reviewed rubrics that critique students for not maintaining sustained eye contact with interlocutors or audiences. In many cultures (Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Middle Eastern, etc.), sustaining eye contact is frowned upon or considered rude. Gender, too, plays a role here.

Anthropologist Edward Hall created the field of intercultural communication when in 1959 he published The Silent Language. Hall defines intercultural communication “as a form of communication that shares information across different cultures and social groups.”

Hall calls our attention to how communication styles vary between high-context and low-context cultures, which refer to the value cultures place on indirect and direct communication. The communication rubrics in place in most U.S. schools are grounded in the fact that the dominant paradigm creates a low-context culture.

In Asia, I have worked with students in Chinese and Korean schools, guiding them through short-term projects. My partners and I struggled to assess these students with Western-anchored presentation rubrics that were translated in word but not culture. I now have similar issues with non-European students in the U.S.

Collaboration

My team spent a couple of years developing curriculum and teacher training programs with partners at the Korea Development Institute. I was utterly fascinated when we assigned table talk and group work to teams of teachers and staff. The most senior member of the group (almost invariably a man) did the majority of the talking and virtually dictated what and how the group would present. But when it came time to present, the senior member picked the least senior member of the group (invariably a woman) to do all the talking.

This is very different from the egalitarian collaboration that Western teachers expect. Research by Michelle Gelfand, Lisa Leslie, and Ryan Fehr, (2008) argues that North Americans “have the motivation and the autonomous freedom to make choices that please the self rather than others in the groups.” Conversely, research by Richard Nisbett and his team (2001) acknowledges that individuals from Asian cultures “tend to be motivated to act in ways that promote group cooperation and harmony.”

The Latinx students in my classroom struggle with collaboration for a number of reasons. I keep reminding myself they are not members of a monolithic culture. Some of the students are third-generation Americans and others are new to the country from Mexico, Central and South America. I see the need to be more culturally adept in my collaboration training and to excise elements of a rubric rendered ineffective by cultural assumptions.

Creativity

I have struggled the most with teaching and assessing creativity. Most of the rubrics you’ll find online exhibit the same struggle, including the categorization of this 21st century skill. That’s why many of these rubrics are labeled “creativity and innovation” or “creative problem solving.”

Teaching and assessing creativity is hard enough, but true to our theme we really have to be aware of the culture influences on creativity and how that impacts student work.

My favorite summary of this topic was explored in depth by a team from Guangxi Normal University (2019) in a research summary entitled How Does Culture Shape Creativity: A Mini-Review. The authors cite the work of Elisabeth Rudowicz (2003) and James Kaufman and Lan Lan (2012) when offering this explanation of the significant difference between creativity in Western and Eastern cultures: “… the emphasis on novel or groundbreaking outcomes fits better with the Western or individualist belief system, which is based on the ideals of individuality, freedom, and democracy. In contrast, the focus on usefulness reflects a strong reliance on tradition, and Eastern or collectivist societies, which are firmly grounded in the ideals of interdependence, cooperation, collectivity, and authoritarianism, have evolved a distinct perspective on the inherent meaning of uniqueness, originality, and/or novelty.”

Critical Thinking

As indicated in the story about my wife and how she thinks, critical thinking is not free from the influence of culture.

ASCD sells a popular book on the topic. In Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking, Douglas Brenner and Sandra Parks offer a chapter on the cultural influences that impact critical thinking. The authors share this nugget: “Because our habits of mind are influenced by our cultural and historical circumstances, the decision-making strategies that we seek to promote in students reflect our own culture. These schemata are not necessarily universal models that apply across all ethnic and cultural groups (Kim & Park, 2000; Paul, 1993).”

To emphasize that point, a team from Hanoi National University (2018) argues that “critical thinking is not context-free. It has to be congruent with social, cultural context in which it roots and functions.”

When I review the way I assess critical thinking, mostly using a rubric developed by colleagues at the Buck Institute for Education and modified with research completed by the Learning Sciences team at Pearson, I realize that I woefully undervalue the influence of culture on how my students demonstrate critical thinking.

Call to Action

The first step of this process is calling attention to the implicit cultural biases that may impede our goal of teaching every learner to be competent in the essential skills of creativity, collaboration, communication, and critical thinking. Once we have acknowledged that bias we can begin to identify it in the instruments we use to teach and assess these skills. Most notably, 4Cs rubrics.

Educators are likely to begin tackling that task in the next few years with the assistance of a new consortium of non-profits that are partnering with enlightened corporations to create new content around the 4Cs. This new entity will launch later in 2020, ushering in I hope a new vision for the teaching and assessing of 21st century skills that is anchored in cultural awareness and amenable to differing ways of expressing competence.

For more, see:

- Why The Four Cs Will Become the Foundation of Human-AI Interface

- Helping Young Children Build 21st-Century Skills

- Are Cultural Competence and Global Competence the Same Thing?

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.