Where Lifelong Skills and Curriculum Meet

By: Tynetta Harris

I’ll never forget the day I walked into my first college English course.

My professor asked the class to form a circle and debate the themes from our reading assignment. My stomach dropped. I knew how to defend my argument on paper, and I could easily talk to my professor individually about my views, but I wasn’t sure I could discuss the text with my peers. Why? Because I never mastered the skills needed to defend a thesis in a group setting. In high school, I had shared my feelings on literature with my peers, but I was never asked to create an evidence-based argument and discuss our position in a group. How could this be? I went to a great high school with great teachers, but I was never required to use textual evidence to verbally defend my point while listening to what everyone else had to say.

Experiences like this are catalysts for many who become educators. We want to ensure students are learning lifelong skills, like the ability to verbally defend ideas, that will stay with them long after exams are over. As a 9th and 10th grade ELA teacher, I often remind my students I am not just preparing them for their next year in high school—I am preparing them for success in the workforce and in life. I do this by crafting learning experiences that allow students to practice useful skills while mastering curriculum.

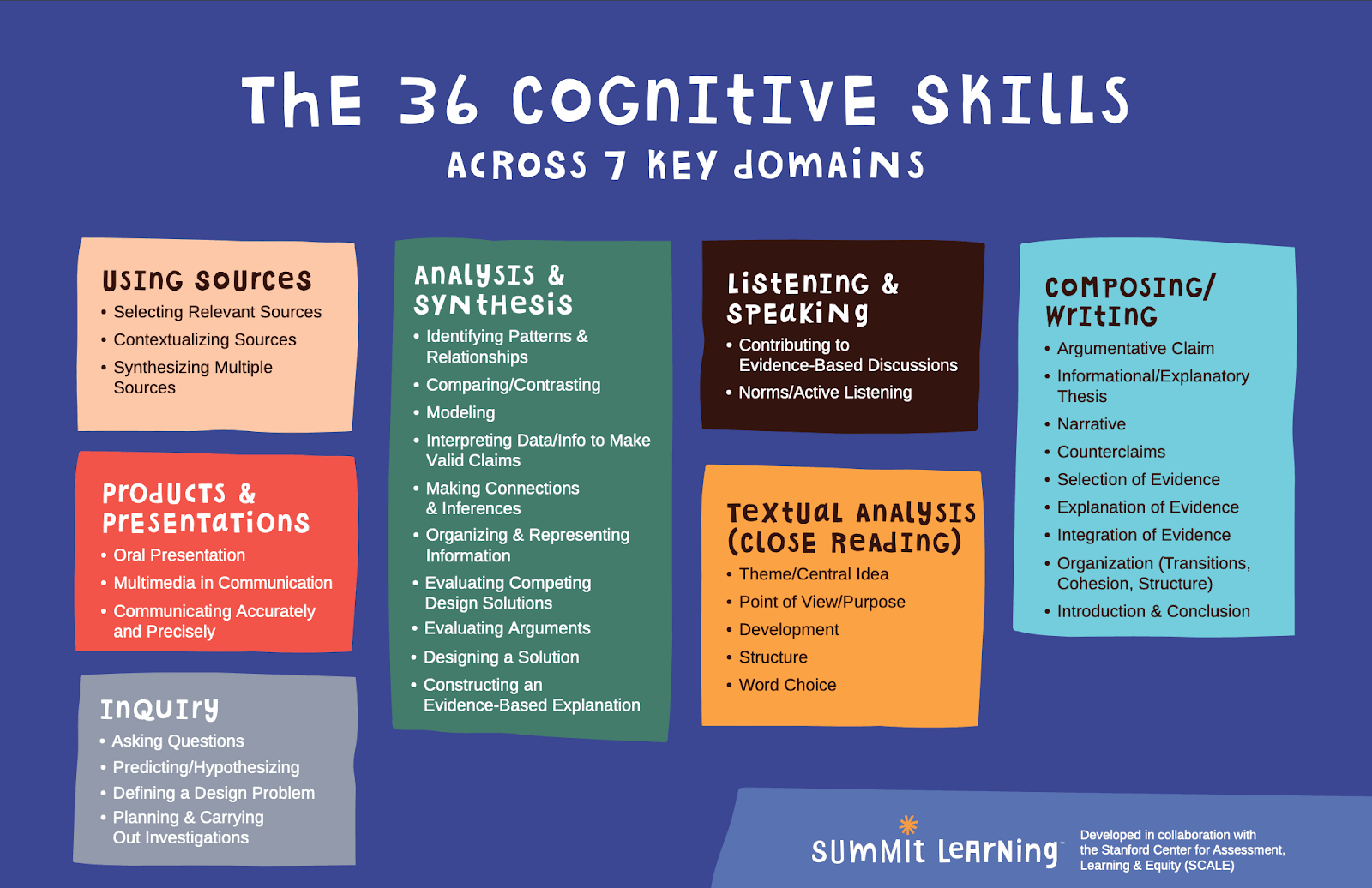

It can be hard to balance teaching core content and skills at the same time, but one example of an academic approach that balances quality curriculum with life skill development is Summit Learning. This approach includes a focus on student development of 36 cognitive skills. These skills, derived from research-based standards, are key to deeper learning. Cultivating this many cognitive skills can seem overwhelming for anyone, let alone a teenager. We make it approachable for students throughout the course of the academic year by focusing on a few skills at a time, tracking progress, and allowing students to truly master skills before taking on new ones. I believe these skills—such as collaborating with a team, interpreting data, and presenting a persuasive argument—can be applied across disciplines and support lifelong learning.

Introducing and Teaching Lifelong Skills

The key skills that are developed in oral presentations and small group discussions are Argumentative Claim, Evaluating Arguments, Contributing to Evidence-Based Discussions, and Norms/Active Listening.

As I found out in college and my career, these skills are key to success in the post-high school world. In today’s society, students must be able to read, analyze, and evaluate informational literature to create a sound argument based on the facts, not feelings, and then be able to articulate that argument with diverse audiences.

I introduce these lifelong skills to my classes early in the year. Before we start a new class project, we first talk about how students can use the skills learned in the exercise outside of the classroom. I intentionally make these examples approachable for my students so they go into their first project with an understanding of the content they are learning and why it is important.

Many high school freshmen have never had to present a persuasive speech or make a presentation. I find that most, if not all, students can hold a discussion about how a text made them feel, but just explaining how reading material made one feel isn’t enough. When it comes to developing strong argumentative claims, it is important for students to practice verbally articulating a clear and cohesive answer to a prompt, provide textual evidence to support their answer, and then thoroughly defend their thesis.

Integrating Presentations and Small Group Discussions

Practicing in small group discussion circles is an effective activity to help build the underlying skills that make for strong presentations and persuasive arguments. In my classroom, I work with my students to create goals for their presentations, and I ask students to reflect on how they attained the goals they chose to aim for. Each student selects a partner with whom they share feedback: how they contributed to the seminar, what they did well, and what they could do to improve for the next small group discussion.

I have seen how these skills are leading to increased student achievement and engagement. I have one specific student who reminded me a lot of myself during my freshman year in college. She is a great writer, but never felt comfortable enough to actively participate in group discussions and presentations. Debating a text’s meaning with her peers was new territory for her. After our first project, I met with her to provide additional support. We made goals and discussed strategies that help build confidence during presentations. She remained quiet during in-class discussion, only speaking once or twice. Each week, we would have a coaching session to give her an opportunity to self-reflect and make a goal of contributing slightly more each session. Little by little, she started to engage more and more until one day, she turned the corner, and asked if she could lead the class in discussion. She not only provided her answer and supported it with textual evidence, she encouraged other students that were not speaking up to join in on the discussion. She offered rebuttals and connected to other students’ points, and when it was over she had a huge smile on her face. She finally mastered the skills of Argumentative Claim, Evaluating Arguments, and Contributing to Evidence-Based Discussions. But, more importantly, she gained the courage to find her voice in an academic setting through continued practice and support.

Every student deserves the opportunity to be well-prepared for post-high school success. As educators, we have the responsibility to ensure that every single student in our classrooms deeply understands the concepts and skills they are being taught, and we can do this by infusing skills development into our curriculum.

For more, see:

- The Future of Work Is the Future of Lifelong Learning

- 10 Reasons Why Lifelong Learning Is the Only Option

- 5 Ways PBL Facilitates Lifelong Learning

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

Tynetta Harris teaches English Language Arts in New Jersey’s Snyder High School. Tynetta has been an educator for over 9 years and believes it is important for students to be prepared for both professional and academic success. Tynetta Harris is also distinguished as one of the 2018 Teachers of the Year. Follow her on Twitter: @EducatorTDot

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.