Hand in Hand: Exploring Bilingual, Multicultural PBL

Among the windswept mountains and rolling hills of the Western Galilee, a brightly painted concrete school set among olive trees welcomes primary students from Sunday through Thursday.

They’re typical first-through-sixth graders. On this particular morning, some chatted excitedly while waiting to board a bus for a field trip. Like most K-12 students in Israel, they wore sweatshirts and tees emblazoned with their school’s logo. As in all of the country’s schools, an armed guard screens visitors behind a metal gate.

What’s different about this group is its diversity: the public school’s 250 students are Christian, Muslim, Jewish, and Druze—some from secular families, some religious. In terms of the two largest ethnic groups, Jews and Arabs, enrollment percentages are almost balanced.

The school’s distinctive approach to education—one that is bilingual, integrated, rigorous and compassionate—has attracted national and global attention for over two decades. It’s run by the Yad b’Yad (Hebrew for ‘hand in hand’) Foundation and was one of the bilingual network’s first two primary schools.

The nonprofit organization was founded in 1998 by two Israeli entrepreneurs, one Arab and one Jewish, with the idea to promote a collaborative, peaceful coexistence from a young age through education. Its nationwide network now boasts a student population of nearly 2000, with some schools putting interested families on a waiting list.

Yad b’Yad is special in a country where the Ministry of Education operates separate schools for every sector to serve Arab, Muslim, Druze, Christian, Orthodox and secular Jewish populations—a departure from traditional systems in Europe and the United States.

As a result, most kids outside of the country’s mixed urban centers such as Jaffa, Haifa and Jerusalem don’t often meet others from different backgrounds. Substantial interaction may only take place after high school, in the army or in college.

A question remains: can schools like this one help bridge cultural gaps between people who have historically been in conflict with one another?

Leading by Example

“I don’t use terms of ‘peace’ or ‘coexistence’—me specifically—but rather, to meet, to collaborate, to talk, to become more familiar. This is my vision for our school.”

Manar Hayadre (featured photo) is in her second year as principal. Her office is abuzz with activity, as its busy staff converses in Hebrew and Arabic with educators, parents and visitors. She’s fluent in both, as well as English, and is pursuing a doctorate in the linguistic interpretation of Semitic scripts.

An Arab who grew up in the multicultural city of Jaffa (part of Tel Aviv), Hayadre was born into a Muslim family, raised by a Jewish grandmother, and attended Catholic school.

“This background helps me a lot with my work here,” she said. “And it’s very meaningful for me to be here, as a principal and as a leader of this school. When I heard this position was available, I said, ‘this is for me!’ My kids—I have three—studied here. As a mother and as an educator, it was the right place for me to make an impact.”

Prior to Yad b’Yad, she’d landed a job as an English teacher after moving to the north of the country. Her husband initially cautioned her against working in a Jewish school—that she may not be accepted there. With largely segregated populations, the area wasn’t as diverse as Jaffa. She accepted and became the school’s only Arab teacher. Over 12 years, her role expanded from homeroom teacher to school leader.

The new challenge at Yad b’Yad offered Hayadre the chance to grow a program she believes in to benefit a broad demographic and geographic base. Parents, community leaders, professionals and clergy from neighboring towns and cities play important roles at the school.

Her team of educators and administrative staff, a mix of backgrounds, reflect the type of equilibrium the school strives for in its student body.

“A minority will always seek to be part of the majority, not vice-versa,” she said. “So the fact that our staff and our students are mostly balanced in this area, which is not a mixed city is impressive.”

Embracing Multicultural Project-Based Learning

Attaining this balance is a result of the significant effort the team puts into its ideology and pedagogy. The combination of project-based learning (PBL), learning-by-doing, and mentorship is unusual in this environment and attracts educators and families from surrounding areas.

Students work on four projects annually. Teachers prepare over the summer, meeting for a week and deciding upon problems, with internal training provided for those unfamiliar with PBL. Projects are publicly showcased twice a year, in January and June.

The approach reflects other PBL models around the world. Questions are connected to social issues, highlighting a problem experienced in Israeli society or students’ local communities.

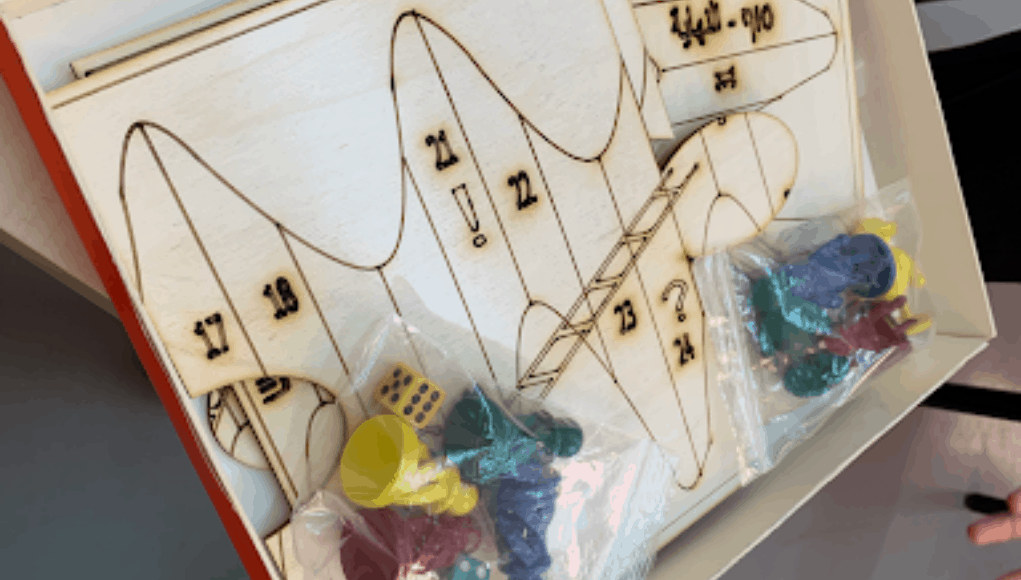

Last year, for example, sixth graders sought to answer the question: “how do we raise awareness for people with disabilities?” The kids researched the topic, interviewing individuals with disabilities, as well as those working for supporting organizations. Ultimately, they produced a tangible product that speaks to the issue—a board game constructed with a laser cutter and a 3D printer from a nearby school.

Hayadre’s team invited the community to participate, playing the game and prompting dialogue and conversation about challenges and ways accessibility might be improved.

Another group took the digital route, creating a computer game. A professional from the high-tech industry was brought in as a mentor. Other students wanted to create a song, so school leaders contacted a professional musician, who composed one with them. They recorded it in a studio.

“We always work with experts; if we don’t have the knowledge in-house, we seek out those of diverse backgrounds in the community,” Hayadre said.

Projects aren’t specifically geared toward integrating students of different cultures, though. “If we talk about collaboration, using differences to do something good for a community and leveraging one another’s strengths—for example, ‘I’m Arab, you’re Jewish, I’m good at math, you’re good at art’—then despite our backgrounds, we use our skills to accomplish something collectively,” Hayadre explained.

Her office is full of their work.

- Fourth grade students are currently writing a play about multicultural relationships. They’re making elaborate puppets, developing a dramatic plot and set of characters, and will present their work in a community performance.

- A multicultural calendar made by second graders served as a fundraiser. Hand-drawn, bilingual seasonal depictions include holidays and important dates in students’ respective faiths.

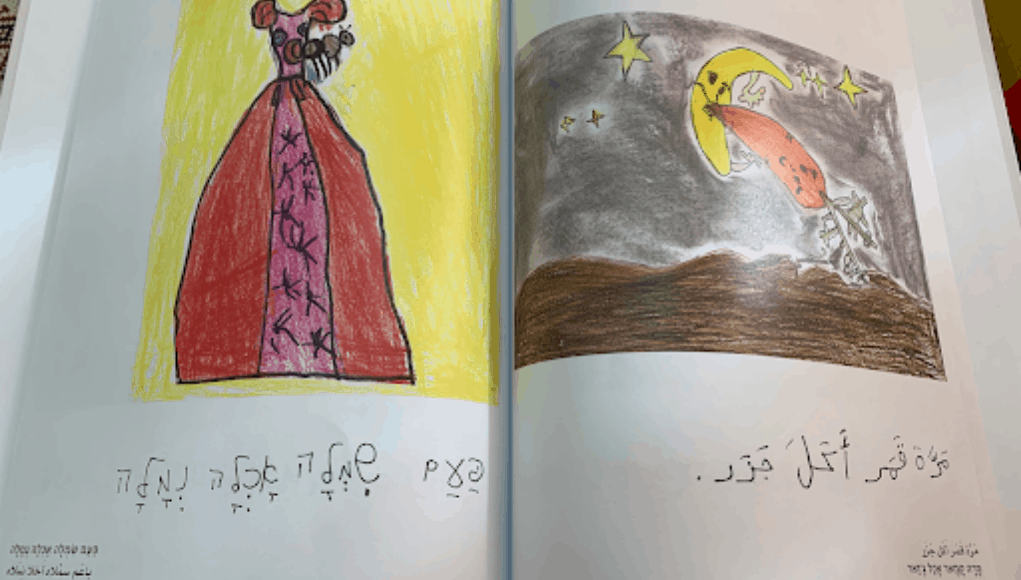

- First graders learned how to write in two languages by creating a book of ‘shtoozim’ (silly rhymes). With the guidance of professional authors and illustrators, students made illustrations, writing each sentence in Arabic, then in Hebrew.

A Bilingual Education from Scratch

First days of school can be stressful—especially when not operating in your native tongue. Here, first graders show up with no knowledge of what will become their second language. In mixed cities, Arab kids will likely know some Hebrew out of necessity and a desire to integrate, but it’s less likely that Jewish kids will know Arabic.

At Yad b’Yad, Hebrew- and Arabic-speaking homeroom teachers co-teach first graders at all times, except during the language class where Jewish students learn Arabic, and Muslim, Christian or Druze students study Hebrew. “Our students’ young minds are so flexible they’re picking things up really fast from context clues in lessons and in conversation,” Hayadre said.

By sixth grade, Arabic speakers are essentially fluent in Hebrew. Hebrew speakers can talk in Arabic, but not as well as their Arab counterparts. A minority-majority dynamic is at play, as for minorities to thrive, they must be highly fluent in their second language.

By sixth grade, Arabic speakers are essentially fluent in Hebrew. Hebrew speakers can talk in Arabic, but not as well as their Arab counterparts. A minority-majority dynamic is at play, as for minorities to thrive, they must be highly fluent in their second language.

Students hear the spoken Arabic language but study the written form—it’s like having two languages within one, so mastering it is difficult and time-consuming. (Upon Hayadre’s arrival at the school, they began to focus on spoken Arabic.)

A linguistic divide often remains, however, as Arab parents are bilingual, while Jewish parents typically are not.

Still, a strong community is being built across cultures and languages. Toward the beginning of each academic year, the staff conducts individual home visits for each child, where they get to know students and their families better. This practice takes place continuously throughout the years children are enrolled in the school, and encourages open dialogue on a range of topics, as well as greater parental involvement in the school’s activities.

Social-emotional learning figures prominently. Homeroom teachers serve as mentors, each working with 12 or 13 students. Three times a week, kids engage in discussion circles—to explore feelings, politics and religion while learning how to communicate about any age-appropriate topic of importance.

During the year, some national holidays can trigger strong emotions. Independence Day (also known as the Naqba) is a celebration for Jews; for Arab students of Palestinian descent, it’s a day they lost their homeland.

“In first or second grade, we talk about the meaning of home,” Hayadre explained. “In fifth or sixth grade, we explore different perspectives, examining historical papers, documents, and videos. We discuss my pain and your pain; my joy and your joy. Sharing perspectives and finding some commonalities enables us to appreciate and acknowledge others’ emotions, and to show empathy for other narratives. Our students understand there are different points of view to each story.”

Mentors hold 1:1 sessions to check in on students’ personal issues, including friend dynamics and any academic challenges, with the aim of helping each student to reach their goals holistically.

Facilitating Long-Term Success

Where do students go after sixth grade? After experiencing this kind of learning environment, many might hope to continue.

“It’s a very sad story,” Hayadre explained. Students return to their own local schools in separate towns and cultural enclaves.

“We’d like to launch a junior-senior high school here. It’s our vision to carry on the process and the mission. But it’s challenging in terms of balancing out the student population and having the resources to build and sustain it.”

Yad b’Yad recently followed up with the school’s young alumni after five years, finding that past students were actively serving as leaders in their respective schools. Many had maintained friendships with those of other backgrounds, which requires deliberate effort when not immersed in the same environment day after day.

The expansion represents a challenge, however, as the school’s model is a costly one. The school receives money from the Ministry of Education as well as Yad b’Yad. But the government doesn’t fund a second teacher in every first and second grade class, and the school’s average class size of 26 to 28 is considered unusually low in Israel. (Subjects such as PBL and school parliament in third grade and beyond also have two teachers.)

This is where ensuring enrollment counts. In addition to PBL, education for democracy is another central theme. “We want our kids to be entrepreneurs, problem-solvers, critical thinkers,” Hayadre said. “We build platforms where they can make smart decisions and effect change, where they try to convince me, the school or the municipality to change something they don’t like. We’ve worked on how to build arguments, how to present ideas, convincing others, and public speaking. They raise issues monthly for a vote within the school parliament and our community.”

Without numerical scores, Yad b’Yad report cards are labor-intensive endeavors. Students’ self-reflection appears on the first page, but will soon be replaced with goal maps, which prompt each student to consider their emotional state, as well as personal, academic and professional aspirations. Teachers report on students’ progress in each subject, evaluating their abilities, and portraying their skills and motivations. A letter from the child’s parents also is included.

“We believe that parents, teachers and students all play a vital role in a child’s education. My staff and I are always considering how we as educators can help, and what can the school do to further facilitate it.”

For more, see:

- Service-Learning: Essential Curricula for Developing 21st Century Skills

- Why We Should Test English Language Learners in their Home Language

- The Development of High-Quality Project-Based Learning

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.