Demonstrating and Assessing Mastery, and Managing Mastery Learning Data

By: Scott Ellis

As I described in my previous blog, the starting point for mastery learning is the learning objectives and mastery thresholds; what do we want students to know and be able to do, and what does success look like? Once these two elements have been defined we are ready to address the remaining key elements required to bring mastery learning to life in the classroom: how students demonstrate that they have mastered the learning objectives, how teachers assess those student demonstrations of mastery, and how the data about the mastery learning progress of the students is organized and displayed.

How Students Demonstrate Mastery Knowledge and Skills

With learning objectives that are specific, clear and demonstrable and with mastery thresholds that are clearly defined, determining approaches for students to demonstrate mastery is a relatively straightforward two-step process. First, we must determine the type (or types) of demonstration(s) a student will use for a particular learning objective or subject area. For example, in the case of many elementary math objectives, solving problems accurately and relatively fluently is a common approach. For an English Language Arts objective like identify the theme of a story’ a teacher may have a student write a response or perhaps present her learning. In the case of some objectives in Social and Emotional Learning, like treat others’ belongings with respect, the student will need to consistently exhibit a particular behavior.

Once the type of mastery demonstration has been determined, the next step is to define specifically how it will work for the particular learning objective, what exactly will the student do? If they are solving problems, what kinds of problems and in what format? If they are doing a presentation, what kind of presentation, in what context, how long, etc.? There can be multiple approaches for students to demonstrate mastery as long as each of them is equally valid and sufficient for demonstrating mastery.

It may be helpful to walk through a couple of examples of this thought process. If a student says, I know how to multiply, how might we think about how the student would demonstrate mastery? First, we would need to clarify the learning objective since the student’s statement could mean a variety of different things. A more precise objective would be I can multiply two one-digit numbers. This is specific, clear, and demonstrable. How would we know if the student has mastered this objective? We need a mastery threshold.

Sometimes the nature of both how the student demonstrates mastery and how the teacher assesses mastery are inherent in the definition of the mastery threshold, and the first step in defining the mastery threshold is to determine the appropriate type of mastery demonstration. In this multiplication example, a reasonable way for a student to demonstrate that she can multiply two one-digit numbers is for her to solve problems accurately and reasonably fluently. So the threshold might be nine problems correct out of 10 within three minutes. With this clear learning objective and mastery threshold, the approach for the student to demonstrate mastery is straightforward, she is presented with 10 problems of one-digit multiplication and she tries to solve them. In Spanish Interpersonal Oral we might use a similar process to come up with a learning objective such as answer three highly familiar, open questions about daily life with single, complete sentences, and for the mastery demonstration, the teacher would ask the student appropriate questions and evaluate the responses.

The other key success factor for students demonstrating mastery is that the approach (or approaches) must be scalable; every student must be able to effectively attempt to demonstrate mastery for every learning objective. And since in a mastery-based system students may need multiple attempts to succeed, the approaches must enable this as well.

How Teachers Assess and Analyze Mastery Learning Student Data

Once it is clear how students will attempt to demonstrate mastery, the approach for teachers to assess whether these attempts have been successful must be just as clear. The approach to be used is directly related to the method used by the student. There are a few key considerations:

1. Feasibility. The teacher must be able to effectively determine whether the student has demonstrated mastery. This may seem self-evident, but it is still very important to be sure that the teacher is able to evaluate the student’s work and decide either that the student has demonstrated mastery of the learning objective and is ready to move on, or that the student did not do so and needs to keep working on the same objective, perhaps with a different approach for learning. If the teacher cannot provide an accurate determination, this usually means that the learning objective or the mastery threshold is not sufficiently clear, and so the remedy is to work on these other elements to enable effective assessment of mastery by the teacher.

2. Inter-rater reliability. Different teachers must give relatively comparable assessments of mastery. This issue is not unique to mastery learning, but it is an important element of the process. Teachers should have a common understanding of the learning objectives and the mastery thresholds as well as how they will assess the student demonstrations of mastery. This will help to ensure that the mastery determinations made by different teachers are consistent. Inter-rater reliability is also honed within teacher learning communities when teachers can use specific, clear data about student performance on objectives to align, share, and grow.

3. Scalability. The process must work for every student, every learning objective, and every teacher. This is particularly important in content areas where students may demonstrate mastery of more discrete learning objectives (rather than just taking a big comprehensive test as they would in the existing system). The workload for the teacher must be managed so the task of assessing mastery does not become overly burdensome and therefore detract from the learning process.

4. Workload from repeated attempts. Since students may need multiple attempts to successfully demonstrate mastery, teachers need time to assess multiple attempts. This will add to the teacher’s workload, and so the process must be designed to be manageable even when some students need multiple attempts.

5. Automatic grading. This capability could improve the overall process in several ways. First, it saves teachers significant time. This is extremely valuable since teacher time is so scarce and precious. It also forces clarity about the mastery threshold–without a very precise threshold it is not possible to design a productive automated assessment. It eliminates any questions about teacher judgment when determining whether students have demonstrated mastery. And finally, it resolves any concerns about inter-rater reliability. However, many content areas and learning objectives cannot be assessed automatically, and even the most effective implementations of automatic grading are most productive when combined with teacher judgment. Educators need to diagnose assessment outcomes and may even override the results when necessary based on the educator’s knowledge of the individual student and her learning needs.

How To Organize and Display the Mastery Learning Data

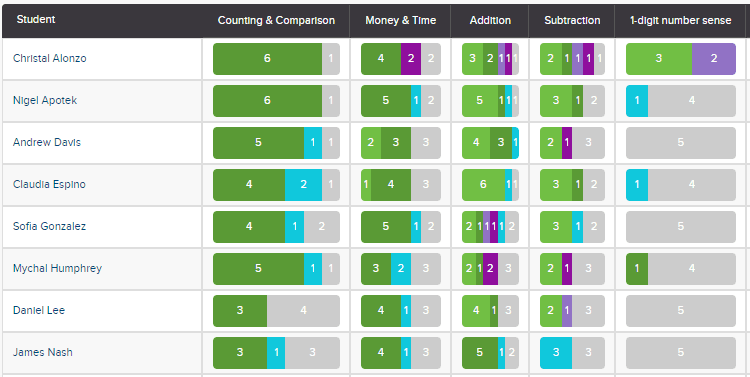

The last essential element is a system to effectively organize and display the data about mastery-based student learning progress. This can take many forms and be provided by a variety of software or online systems. The key is for students and teachers (and also principals and parents) to instantly be able to see where students are in their learning. Dashboards and similar formats serve this purpose well. The main challenge in creating a good dashboard is to show the right kind of data at the right level of detail, and much of this is based on the learning objectives and mastery thresholds. The system must also be scalable at a minimal cost.

With a mastery dashboard (example above) in place along with the other four key elements, mastery learning can thrive in the classroom and scale broadly.

For more, see:

- The Case for Competency-Based Education

- Mastery Learning Objectives and Mastery Thresholds in the Classroom

- Smart Review | MasteryTrack: Powering Competency-Based Learning

This blog is part four of a series on mastery learning, sponsored by MasteryTrack. If you’d like to learn more about our policies and practices regarding sponsored content, please email Jessica Slusser. For other posts in the series see:

Stay in-the-know with all things innovations in learning by signing up to receive our weekly Smart Update.

Scott Ellis is the Founder and CEO of MasteryTrack. You can find him on Twitter @MasteryTrack.

Jeanna Meredith

Hello gettingsmart.com administrator, You always provide great examples and case studies.