Service Learning: Designed to Motivate and Inspire

By: Liz Pitofsky

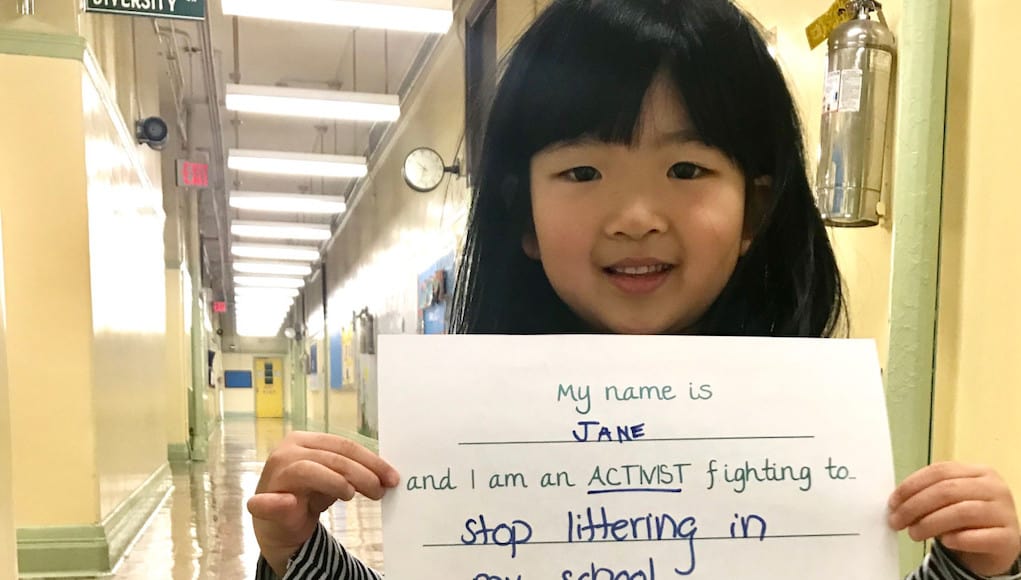

Part of the thrill of facilitating The Service Learning Project (SLP) is seeing the incredibly positive impact on youth of all ages, and there are consistent trends: Students are excited to participate in, but even more so to lead, the process. They are passionate about working together to help solve a social problem of their choice. And they are energized by the opportunity to share their proposals for change with adults in their schools and communities.

“Thank you for letting us express what we think problems are…

Thank you for giving me the confidence that I have now…

Thank you for teaching me that I will be heard if I speak up…

I wouldn’t have cared about this topic if you didn’t come.”

– SLP 4th graders

Why are children and teens so highly motivated by service learning or action civics? Research conducted by Paul Pintrich, University of Michigan professor of education and psychology, points to five essential elements of student motivation, all of which are fundamental to service learning, civics education and the SLP model.

Self-Efficacy

According to the theory of self-efficacy, if students expect to do well, they will try harder, engage more deeply and show more persistence. On the other hand, if students don’t believe they can do something, they find it easier to quit or to feel that a task is impossible.

Service learning and the SLP model promotes student self-efficacy in multiple ways: First, at each step of the process, our faculty convey optimism about the general capacity of young people to create positive change, while also sharing stories about successful projects completed by other SLP participants. Second, we emphasize the unique power young people have to capture the attention of adult decision-makers, which is confirmed during the research phase when students engage with adults who are often moved by their passion and determination. Third, we provide concrete and realistic feedback so that students do not feel overwhelmed by trying new tasks. Similarly, we make sure students do not attempt a new task, such as interviewing an adult working in their school, without sufficient preparation for the challenges that may arise.

Self-Determination and Personal Control

Not surprisingly, research also shows that students who believe they have more personal control of their own learning are more likely to engage. In an SLP project, students drive every step beginning with the selection of the social issue to be tackled. Although faculty guide the process, we ask students to take the lead by deciding what questions to research, which people to interview, which solutions to explore, etc. Even with our younger students, who may not be quite ready to direct the process, we offer multiple options to choose from and then, at each step, follow the path about which they are most enthusiastic.

Similarly, SLP students have tremendous autonomy. Any task, big or small, that a student can handle, we give them the space to do so. Whether it’s collecting information from their peers, facilitating a group discussion or editing a public service announcement (PSA), we encourage our young advocates to take charge and remind them throughout the process that the adults in the room are there merely to assist them in the process. This is very exciting, especially for young people who are accustomed to the more adult-driven approach of traditional classroom settings, and very effective in building their enthusiasm for the project.

Personal and Situational Interest

Tapping into personal interest is, of course, an excellent way to motivate students, which is one of the reasons our model requires that students choose the social issue to be tackled.

Situational interest, on the other hand, refers to how interested students are in specific tasks. By allowing youth to take the lead in determining which activities to pursue, mixing up the activities throughout the process, and adjusting the focus, as needed, to evolve with the students’ growing knowledge about the issue, we ensure that the project stays interesting for our participants.

Value Calculations

Students want their work to be important and not busy work. With each activity, we make sure students understand why we’re doing it and how it will help advance their project. We also take any opportunity for students to appreciate how skills they are developing can be used outside of the SLP process in their academic and personal lives.

Goal Orientation

Students pursue many different goals in the classroom, both individual and social. Individual performance goals that are achieved through action civics include opportunities to demonstrate ability, receive recognition and compare individual progress with that of their peers.

Because social ‘success’ can be strongly related to effort and achievement, peer interaction is key to maintaining student motivation. Small group activities, which make up a significant part of the SLP process, are effective because they promote a sense of belonging to the group, demonstrate responsibility within the group, and provide emotional and cognitive support as needed during a particular activity.

Through work with SLP, we have seen the power of action civics and service learning on increasing the motivation of students. It is my hope that every student will one day experience the benefits of a service learning or action civics project—the benefits to students are profound.

For more, see:

- Ella Baker Elementary Shines A Bright Light On Learning

- Smart Review: Doing Good

- One Stone: Where Purpose Meets Impact

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

Liz Pitofsky is the founder of the Service Learning Project (SLP), a Brooklyn-based civic engagement program for youth in grades K-12. You can find them on Twitter at @TheSLPNYC.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.