What Happens When We Do School Better?

By: Doris Korda

Kylin Mackey was not going to graduate high school.

When students in Columbus City Schools are suspended or expelled they have the opportunity to enroll in Options for Success (OFS). This gives students the choice to avoid missing out on valuable learning, whether they’re there for a few days or several months. For Kylin, the program was his last chance at staying in the system after his most recent expulsion. By the time of his enrollment in spring 2016, his academic record was littered with infractions and he’d amassed a thick disciplinary file. If he couldn’t cut it at OFS, the system was ready to eject him, and what’s worse, he was expecting that outcome too.

When Dr. Danielle E. Bomar became Principal of OFS in 2016 she was determined not just to fix her student’s grades, but their understanding of why their education is important. Doing that started with asking a simple question of both her teachers and her students: Why are we going to school?

”A lot of students these days want to know why,” said Danielle. “It’s not enough to tell them ‘you have to learn this because I’m your teacher and I said so’. They want to know how they’re going to apply what they’re learning.” For Dr. Bomar, “getting students re-engaged in school isn’t just about boosting test scores. It’s about keeping these students from becoming statistics.” According to research from UCLA, even one expulsion can almost double a student’s chances of never graduating high school.

When I met Dr. Bomar, it was clear she was looking for something for the Kylin’s in her school. When she visited my entrepreneurship class and had a chance to see my methods in action, she knew her students needed the same experience. She was eager to move away from “drill and kill” style instruction towards something more student-driven. Together, we decided to do a pilot with a small group of students, a cohort which included Kylin.

Hot Chicken Takeover and a Fair Chance

On the first day of class, Kylin and his classmates weren’t given a worksheet or reading list. They were bussed downtown to Hot Chicken Takeover. The North Market eatery was founded by Joe DeLoss, who had more ambitious goals than simply serving delicious Nashville style fried chicken. Joe sat down with the students and explained how his business practiced “Fair Chance Employment”, giving jobs and opportunity to people affected by a criminal record who otherwise wouldn’t be able to find work. Then Joe issued a challenge. They were opening a second location soon in a suburban neighborhood, where there were questions about how well the community would accept his employees. They were investing so much into it that if they couldn’t get enough new customers and employees, it could put their downtown spot in jeopardy. In just three and a half weeks, he’d be coming to OFS to hear the student’s ideas for how to get his new location up and running.

The social justice aspect underlying the company got Kylin engaged like nothing else could have. “Pretty much as soon as we got to Hot Chicken Takeover, Kylin was the leader,” recalls Dr. Bomar. This wasn’t a problem with an answer in the back of the book. No one – including Joe – knew the correct solution ahead of time, and both he and the teachers made it clear the answers students provided would make a real difference for the restaurant and its staff. Instead of calculating the distance between fictional bus stops or memorizing dates, Kylin was responsible for something real, urgent, and unlike anything he’d ever had to do in school before.

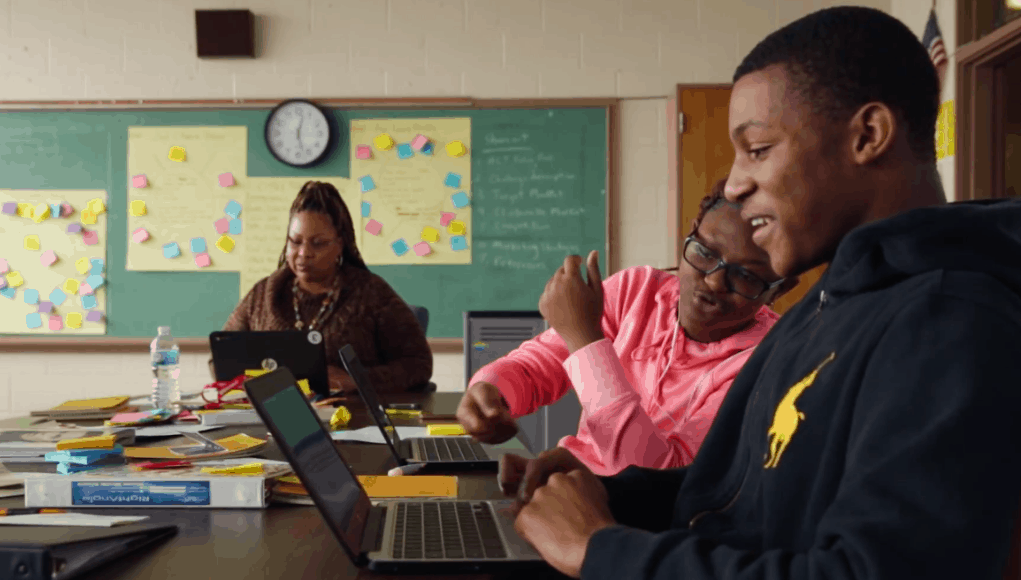

The Pilot: Learning through Discovery

The teachers at OFS weren’t trying to get Kylin to “learn marketing”. They were constructing a space where Kylin could discover his strengths and his ability to make a difference with his teammates and within his community. If Kylin and his team were going to present their solutions to Joe and field questions from him at the end of the project their suggestions would have to be backed up by evidence. That meant learning how to find and interpret data to determine what was relevant and what wasn’t.

Having the students work in teams helped with managing the scale of the project. It also allowed each student to hone in on their particular strengths and build on those so each person contributed the most they could to the project. And since these teams were comprised of teenage humans, another inevitable part of the learning was experiencing disagreements with colleagues and learning how to work through them healthily and productively. When Kylin made a mistake, he wasn’t simply given a bad mark and told to move on; he was given space where he could reflect on what went wrong and guidance to build off that experience.

As Dr. Bomar said after the program, “Kylin didn’t miss a day of school, and his attendance was terrible at his home school before the program. He was late one morning to this class and otherwise had perfect attendance. He did public speaking, research, stuff that he told me he never would’ve done at his home school.”

Transforming Students by Transforming School

Coming out of the pilot, Kylin graduated on time in the spring of 2018. This alone was cause for celebration, but he didn’t stop there. Kylin went on to enter a rigorous automotive engineering program offered by Columbus City Schools that earned him a certification and work with some of the top car companies in the country. “When he came into OFS he was an ‘Academic Emergency kid’,” said Dr. Bomar. “That meant he was in trouble in his discipline, attendance, and grades. But in the entrepreneurship class he had zero disciplinary incidents, he was only late one day, and the academic work he did was outstanding.”

“These students gave one hundred percent,” added Dr. Bomar, reflecting further on the pilot’s success. “And knowing their histories, I don’t think any of them gave one hundred percent academically to any class or program before. This was the first time they were recognized not for sports or doing something wrong, but for what they did in the classroom.”

What it took to produce this result was a leader and teachers with the will to make a change. This allowed for a student who was on track to becoming a statistic to be recognized not for a disciplinary issue or athletic achievement, but for his ability to work with others, develop complex ideas, and present them with sophistication and evidence to back them up.

“I didn’t even want to do it at first,” said Kylin after finishing the class. “I was thinking I’d skip out and go back to regular class. But we started sharing ideas and combining them…and, it made our project even better. We got to just get up and be ourselves.”

Giving Kylin the opportunity to learn and in a meaningful way didn’t just improve his academic performance, it turned him into a bona fide leader. All he needed was a fair chance in school.

Short Documentary: Kylin’s Experience

For more, see:

- New School Formula: Harder Problems and Fewer Answers

- Helping Students Prepare for Their Futures on Linkedin

- Advancing Equity Through Innovation: 7 Noteworthy Approaches from Brooklyn LAB

Doris Korda is the founder and CEO of Wildfire Education. To learn more about Doris’ work, visit Wildfire-Education.org. Connect with Doris on Twitter at @DorisKorda.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.