How Formative Assessment Transforms the Classroom, From Culture to Lesson Plans

By: Brea Lewis and Michelle Berkeley

Using formative assessment requires a willingness to embrace change at all levels–from guiding mindsets, philosophies and classroom culture, to daily schedules and lessons plans. Brea Lewis, third- and fourth-grade math teacher at Ben Milam Elementary, recently confirmed this idea when she reflected that through the incorporation of formative assessment practices, “our lesson cycles have changed significantly.” We explored just what those changes look and feel like in her classroom since transitioning to formative assessment.

Ben Milam Elementary is one of several Dallas ISD schools involved in a three-district collaborative pilot project entitled “How I Know,” an initiative of the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation. Through this initiative, leaders and teachers from Dallas ISD, Austin ISD and Tulsa Public Schools have committed to learning about, developing, and improving formative assessment practice for both teachers and students.

To demonstrate how formative assessment has impacted learning in Brea’s classroom, we started by uncovering the large-scale effects of formative assessment on the teacher and students’ roles in the classroom, and also in the overall classroom culture. We then share Brea’s perspective on how formative assessment has impacted the delivery of one specific lesson and her tips for successfully transforming to a formative assessment classroom.

The Formative Assessment Transition Process

In Brea’s classroom, the transition to formative assessment began at the start of the 2017-2018 school year. In speaking with her, it is evident that the training and exposure to professional learning tutorial videos (such as The Formative Classroom and What is Formative Assessment?) gave her more command and confidence in her practice, especially with creating Learning Goals and Criteria for Success–two key elements in the formative classroom.

Shifting the Focus from Teacher to Student

Shifting the Focus from Teacher to Student

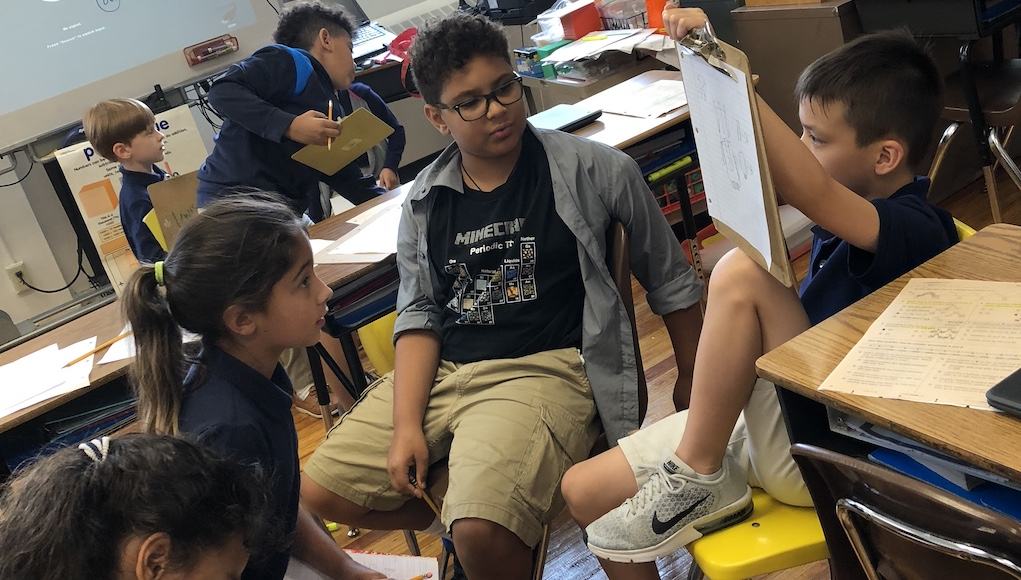

Reflecting on what’s different in her classroom, she is quick to identify that lesson cycles have become notably more student-centered, and that students have become both more independent, and more interdependent on one another rather than the teacher.

She explains that one old lesson plan was highly teacher-focused and teacher-controlled, and identified exactly where the teacher was and what the teacher was doing at every step in the lesson; this often would mean she was meant to be present at every table of students and facilitating every small group at once. This created an atmosphere where students were highly reliant on the teacher’s help, and teachers then didn’t have the opportunity to take part in learning themselves.

A new lesson plan now focuses more on questions like “what are the students doing,” and “where are the students,” and by changing the focus from teacher to student, students are gaining ownership over their learning and starting to act autonomously and collaboratively among one another.

Incorporating Learning Goals and Criteria for Success

Perhaps most important to the shift, she has found, is that students are involved in the very crux of their learning when they are not simply told lesson objectives and steps, but are expected to fully understand a Learning Goal and its purpose. The process of then rewriting that in their own words or adapting it to fit their needs, co-creating the Criteria for Success, brainstorming “how do we get to the learning goal,” and then determining a plan and trying it out has proven very impactful.

Students have choices and free range within the Criteria for Success, and take part in deciding what they personally need to work on. In Brea’s classroom, at any given time, students are working on different criteria or tasks and displaying more ownership over their personal progress. “[Students] don’t say ‘I don’t get it’ anymore–they say ‘I’m stuck on this and this and this, and I need to work on this specific thing,’” she shares. In her classroom, each student collects the Criteria as they earn them, and this becomes tangible proof of their learning – often something students take great pride in obtaining.

The Lesson Plan: Before and After

At the same time, there is a shift that takes place in the teacher’s role, wherein they are no longer directing students through each step in a given lesson process, but rather observing and guiding the pace of learning. Below, Brea shares a sample lesson cycle before and after formative assessment practices were introduced, and the changes that took place in one fourth grade math class.

Lesson Plan: Before Formative Assessment

In a sample fractions lesson plans from last year, you can see that through the cycle it was more teacher-oriented than student-driven. I provided and modeled the information for students during the lesson, and the cycle was based around a 65%/35% teacher/student-driven classroom (instead being of highly student-driven), as they needed full guidance before being released. Even when students had the opportunity for independent or collaborative practice, they were still being monitored for a certain amount of time before the teacher could work with students who felt they needed more support in understanding of the lesson. The lesson also moved slower before formative assessment, as it took more time for me to reflect on their learning and progress instead of students providing that themselves.

Lesson Plan: After Formative Assessment

With the same lesson adjusted to formative assessment practices, you’ll see that on the first day students are starting a new learning goal in comparing fractions, which starts with discussing our Learning Goal and Criteria for Success. I discuss the learning goal with students, and then they have the opportunity to write what it means to them. After this, students gather to discuss what the steps are to be successful in reaching our goal. After the Criteria for Success discussion, the mini lesson begins–manipulatives and visual representations (drawings) are used along with student experiences such as measuring ingredients for cooking.

After the lesson and once students have gathered more understanding, Independent Practice (IP) begins, where students have options consisting of using Education Galaxy, Khan Academy, using more manipulatives, or coming to the teacher station (based on how they feel with their understanding of comparing fractions).

On the second day, students come in and gather whatever materials they will need based on their own academic reflections on the Learning Goal for comparing fractions. On Wednesday, students start a new Learning Goal in adding and subtracting fractions, which starts with discussing our Learning Goal and Criteria for Success, and the cycle continues.

Four Teacher Tips for Flipping Classroom Roles to Incorporate Formative Assessment Practice

When I reflect on the transition process, what sticks out to me is that it involved asking myself a lot of questions about my students, and my relationship with them. Below are my tips for success to other teachers implementing formative assessment:

- Give students more ownership. Have students become more involved in the learning process by providing them with opportunities for collaborative and independent practice. This can also include having student involvement when building the lesson.

- Change your own mindset to that of a learner to model the change for students. When you change your own mindset to that of a learner, it allows for a deeper understanding of how learning will evolve during a lesson, instead of the goal being just to get to the end of the lesson.

- Make space for student reflections. Allow students to assess their own learning and to communicate feedback.

- Create learning goals and success criteria. Determine specifically what students need to know, and what actions need to be taken to reach the goal, such as “I can look at my fractions and identify like denominators.”

In this snapshot of one How I Know classroom transitioning to a more meaningful and impactful formative assessment practice, we see a teacher observing the development of critical skills in problem solving, decision-making, leadership, collaboration, and independence in her students. Through taking steps to empower her students, she has seen tangible changes in students’ ability to communicate, support themselves and their peers, and engage in their own learning.

While the transition of mindsets has taken time and effort, it has had a valuable impact on student learning.

For more, see:

- How I Know: Impacting the Classroom Through Student-Driven Learning in Dallas

- The Student Role in Formative Assessment: How I Know Practitioner Guide

- Building a Collaborative Culture: From Inspiration to Application

Brea Lewis is a third and fourth grade math teacher at Ben Milam Elementary in Dallas, Texas.

This post is a part of a series focused on the “How I Know: Designing Meaningful Formative Assessment” initiative sponsored by the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation. See the How I Know website (www.formativeassessmentpractice.org) and join the conversation on Twitter using #HowIKnow or #FormativeAssessment.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.