Are Cultural Competence and Global Competence the Same Thing?

People assume that because my sons have grown up in a multilingual and multicultural home they are naturally culturally competent. They assume that because my sons have traveled with us around the U.S. and to a half-dozen foreign countries that they are naturally globally competent.

That may be partially true, but my reticence comes from the use of these terms. What do they mean? Nearly every school in the United States, and from what I’ve seen almost every school around the world, wants graduates to emerge with cultural and global competence. Again, what do they mean? Is there a difference?

I worked for more than two years as CEO of the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, focusing in my tenure on imbuing our Framework with new thinking around global competence. We drew our inspiration from the work being done in North Carolina at the Department of Public Instruction, VIF (now Participate) and the global competence framework developed by the Asia Society and CCSSO.

We took a long, hard look at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) framework, which serves as the concept map for the 2018 assessment of global competence that is now part of the PISA battery.

Let’s jump one semantic hurdle (the meaning of the word “competence”) before we get started. According to the OECD, “competence is not merely a specific skill but is a combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values successfully applied to face-to-face, virtual or mediated encounters.” Development of competence is a lifelong process.

The following global competencies comprise OECD’s four domains. Globally competent individuals:

- Can examine local, global and intercultural issues

- Understand and appreciate different perspectives and worldviews

- Interact successfully and respectfully with others

- Take responsible action toward sustainability and collective well-being.

There are minor differences, mostly semantic, among the various frameworks so this definition will serve as our default understanding of global competence.

Cultural competence is another matter and it’s not only the education sector that has an abiding interest. If you dig into the topic you’ll find that many of the most popular use cases come from the federal government and focus on the medical field.

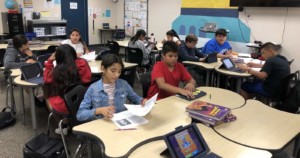

The National Education Association (NEA) shifts the conversation to the classroom with its Diversity Toolkit: Cultural Competence for Educators. In the NEA’s definition, culturally competent teaching incorporates “awareness of one’s own cultural identity while having the ability to understand group differences that make each classroom and even each student, unique.”

The NEA cultural competence framework is driven by a skill set that teachers can develop for the purpose of improving student success in diverse classrooms:

- Valuing Diversity. Accepting and respecting differences—different cultural backgrounds and customs, different ways of communicating and different traditions and values.

- Being Culturally Self-Aware. Culture – the sum total of an individual’s experiences, knowledge, skills, beliefs, values and interest – shapes educators’ sense of who they are and where they fit in their family, school, community and society.

- Dynamics of Difference. Knowing what can go wrong in cross-cultural communication and how to respond to these situations.

- Knowledge of Students’ Culture. Educators must have some base knowledge of their students’ culture so that student behaviors can be understood in their proper cultural context.

- Institutionalizing Cultural Knowledge and Adapting to Diversity. Culturally competent educators and the institutions they work in, can take a step further by institutionalizing cultural knowledge so they can adapt to diversity and better serve diverse populations.

Examine the two constructs: Is one subordinate to the other? Subsumed by the other? Can schools ease initiative fatigue and semantic confusion by focusing on either global competence or cultural competence?

The difference, it seems, is a matter of focus. Global competence prepares students and teachers to look outward to the world for inspiration and guidance and to bring those understandings back to the classroom or workplace. Cultural competence prepares teachers (mainly) and students to look inward toward the classroom or workplace and identify, understand, communicate and celebrate traditions, values and practices that can enrich the experiences of all.

Schools need them both, but a clear explanation for teachers, students and parents would be helpful. The recent focus on socio-emotional learning muddies communication as well, so a school or district would do well to provide on its website a primer that states an official position on these important constructs.

My sons? They have begun the lifelong journey to cultural and global competence. Let’s help all learners begin that journey, too.

For more, see:

- 2030 and Beyond… Will We Really Be Able to Still Compete?

- Educating for Global Competence: 6 Reasons, 7 Competencies, 8 Strategies, 9 Innovations

- How World Language Learning and Global Competence Complement Each Other

- Making Connections: Beginning to Measure New Skills That Matter

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.