On the Ground with Place-Based Ed: Investigating City Plans

By Annie Holub

It was probably the craziest field trip idea I’d ever had. I was sure my principal would say no.

“Hey Brett,” I said casually, walking into his office. “This might be crazy, but I want to take all of the freshmen on the city bus to visit the buildings along Broadway so they can get out and take pictures and talk to the building occupants.”

“Sounds great!” my principal replied to my surprise. “Let me make sure we have enough bus passes.”

That kind of answer is why I love my school and my job. Place-based education is foundational to our school. City High School is located in downtown Tucson, and the name means a lot. We actually get out into our community and use it as our textbook. We’ve seen, time and time again, during the 12 years our school has existed, how learning about the community has the power to engage and activate students’ minds.

As part of my 9th-grade humanities class, called Self and Place, my students every year learn about urban development. One of our Arizona state geography standards asks them to “analyze the development, growth, and changing nature of cities.” In years past, I’d had the students do projects related to our downtown that were not time-sensitive, but this past school year, I wanted to do something more current, more authentic. If we were really going to learn about urban development and how a city grows and changes, why not look at a change as it actually happens?

The City of Tucson was in the process of finalizing plans to widen the main east-west artery into downtown, Broadway Boulevard. People from the adjacent neighborhood associations, business owners, historic preservationists and city planners were all at odds over whether and how to widen the road. The road was one all of my students traveled on every day. Many of them lived right off of it, walked down it or had crossed it multiple times each day for their entire lives. As they sat at their desks in my classroom, the city was planning to dramatically change the feel and function of the road.

Did my students really know much about the buildings threatened with demolition, the different perspectives on the widening project, or how urban development projects like this even happen? How could we ignore this event that was happening right now and affecting such an important part of our city? So we set out to learn as much as we could about the proposed plans and to document the effects on as many buildings and businesses as we could.

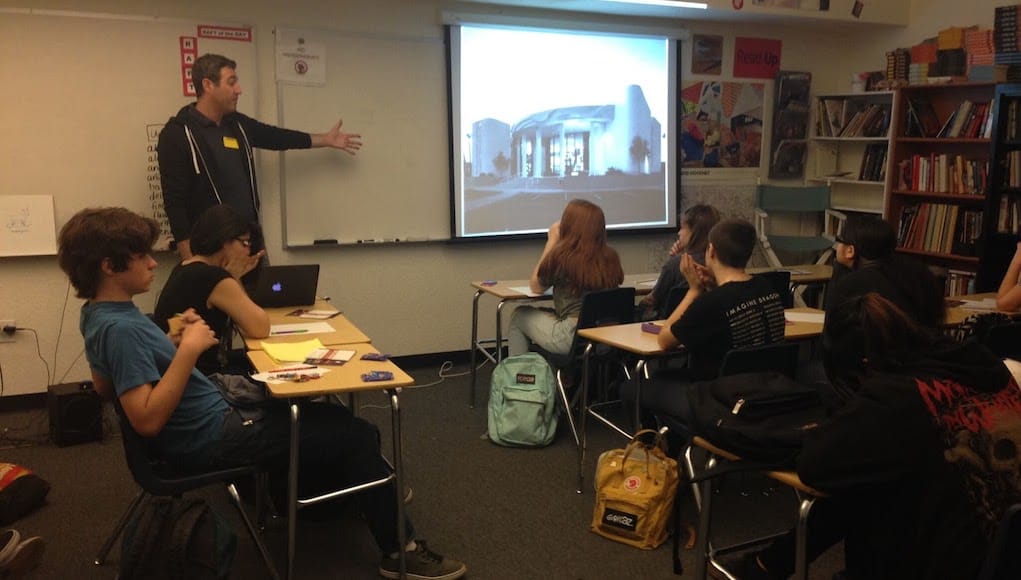

It wasn’t necessarily a beautifully planned, perfect project. That’s the thing about really using your place to guide instruction. As educators, we have to be willing to learn along with our students and let the place be our teacher. First we did a lot of reading. We read opinion pieces and primary-source documents from different stakeholders. They weren’t necessarily the most well written, grade-appropriate texts, but they were real and they were what we had to work with. We analyzed their logic and arguments and learned a lot about the effect of fallacies and overuse of emotion. Then we had guest speakers: the city councilman who represented the area of town that stretch of road is located in and the director of the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. We started to get a sense of what might happen and why.

My students asked a lot of questions. Sometimes, I didn’t know the answers either, and together we tried to figure out who to ask. For the final stage of the project, each student chose a building from a list that the city had compiled of buildings that had historic value. We had learned from our guest speakers that many buildings along Broadway are mid-century modern masterpieces, designed by local and nationally known architects who had their heyday in the 1950s and ‘60s. Hidden between an Office Max and a Dollar General might be a building whose facade features intricately-carved concrete only visible up close, or a Googie-style diner with a space-age tilting roof. We learned that we all needed to look a little closer at the things we saw everyday to really see and appreciate what was there.

So on one sunny day last March, my students and I walked to the transit center down the street from our school, and got on the Broadway bus. We were going to immerse ourselves in this place we were studying and find out what it had to teach us. The first group got off at the first stop out of downtown to document the Googie-style diner as it was being renovated. At the next stop, three more students got off to visit a gorgeous office building that the historic preservationist pointed out couldn’t be built today because the cost of materials alone would be ridiculous. At Country Club, where the proposed widening project will end, several groups got off to visit multiple businesses housed in Tucson’s first shopping center outside of downtown, Broadway Village, built by Josias Joesler in the 1930s.

I went with a group to visit the gorgeous Chase Bank building across the street, originally built for Valley National Bank in 1953, to see what the bank occupants thought about the widening project. Every group took lots of pictures of their buildings that day, which they then used to create presentations for the community. Some groups encountered business owners who were less than friendly and not willing to discuss the fate of their livelihood. One group had the opportunity to talk at length with the owner of a shoe store who was retiring after over 60 years in business. And one group even got lost and ended up on the wrong bus, heading the wrong direction; a small place-based lesson in itself.

Waiting for the bus that would take us back downtown, some of my students and I speculated about what might happen to various buildings we could see from where we stood. The next week, the City of Tucson was set to release more updated plans for the widening project that would determine which buildings were safe, and which would need to be bought by the City and torn down. (Update: The project plans were approved, and the City is in the process of purchasing properties in preparation for construction, which is set to begin in 2018.)

“It’s cool to know that in 20 years, I can tell my kids about how the road looked when I was a kid,” said one of my students. The fact that this particular student, one who hardly ever turned in any “traditional” school work, is thinking about the future of her city, and is planning on still being here, speaks volumes to the power of place-based learning.

For more, see:

- Maritime and Place-Based Learning in a Rural District

- Quick-Start Guide to Place-Based Education

- A Science Program that Goes Beyond the Lab

Annie Holub teaches 9th-grade humanities at City High School in Tucson, Arizona. Follow her on Twitter: @aholub.

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.