Consortium Points the Way on Proficiency-Based Learning

David Ruff is the executive director of the Great Schools Partnership and also coordinates the New England Secondary School Consortium (NESSC), a network of high schools in Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. He’s leading the regional shift from time, to learning as the primary education variable. Ruff calls it proficiency-based, iNACOL calls it competency-based, some use mastery-based–it’s mostly the same thing: kids show what they know and progress as they demonstrate that they’ve met learning expectations.

“David is a great resource for our region,” said Nick Donohoe of the Nellie Mae Education Foundation, NESSC’s primary benefactor. “He has a forward-thinking view of where learning needs to go, related to policies and assessment in particular,” and he’s particularly good at “summarizing ‘edu-ese’ for state legislators and local school leaders.”

Proficiency-based learning simplified. NESSC uses a seven part definition:

- Students advance upon demonstration of mastery of content, 21st century skills, and dispositions that prepare them for college and careers;

- Learning standards are explicit, understood by students, and measurable;

- Assessments–formative, interim, and summative–measure and promote learning;

- Demonstration of learning uses a variety of assessment methods including in-depth performance assessments that expect application of learning;

- Instruction is personal, flexible, and adaptable to students’ needs–both initially and as required by ongoing student learning;

- Students both direct and lead their learning even as they learn from and with others–both within and outside of schools; and

- Grading is used as a form of communication for students, parents, and teachers–not control or punishment.

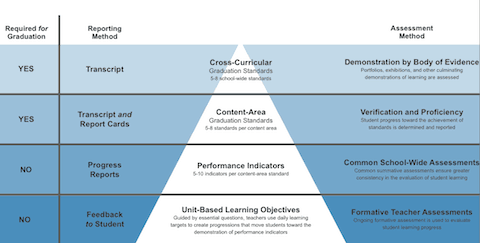

Ruff uses a great chart (featured image) to summarize his advice on how to use standards and assessments to make instructional decisions and big gateway decisions like graduation. The chart includes four levels of expectations–the top two are graduation requirements, the bottom two are not.

Cross-Curricular Graduation Standards: 5-8 school-wide standards

- Demonstrated by a body of evidence: exhibitions and portfolio

- Reported on transcripts and report cards

Content Area Graduation Standards: 5-8 standards per content area

- Verification of proficiency through assessments measuring performance indicators

- Reported on transcripts and report cards

Performance indicators: 5-10 per content area standard

- Assessed using common school-wide assessment to ensure consistency

- Reported on progress reports

Unit based learning objects: daily targets to create progressions

- Formative teacher assessments to evaluate student progress

- reported as feedback to students

Schools can develop Cross-Curricular Graduation Standards and Content-Area Graduation Standards from various resources including state standards and the Common Core State Standards. Staff at the Great Schools Partnership have created exemplar graduation standards which are drawn from the Guiding Principles of the Maine Learning Results, which include the Common Core State Standards and are anticipated to be include in the Next Generation Science Standards, and relevant national college- and career-ready standards documents. Many schools in the NESSC are using the exemplar standards noted above, making small changes to ensure consistency with local context and needs. While these exemplars may not be perfect for every school, they provide a jumpstart for this work for educators.

“We need to think carefully about how we use the common core and how much students can and should demonstrate for graduation. We see a difference between using it to help create curriculum and using it as an accountability mechanism for learning,” said Ruff. “Having common learning standards across the country makes imminent sense, but holding kids accountable to every little nuance of each standard makes much less sense. There are so many of them that the sheer number reduces the ability we have to personalize.”

If students are held accountable to every standard, Ruff thinks, “We ‘personalize’ the rate at which students move through low level standards but pay limited attention to personalizing the learning process or how we engage student interest. Conversely, if we operate from a notion of graduation standards that are at a higher, but more rigorous level of complexity, we can both increase flexibility about how students learn and incorporate student interest.” The result: “We increase both student voice and choice–key characteristics of student engagement and deeper learning,” said Ruff.

Assessment options for proficient-based schools, according to Ruff, can follow three pathways all of which incorporate learning experiences, demonstration tasks, and scoring guides and which can result in quality and comparable results. One pathway has all students engaging in a common learning task followed by a common demonstration task and uses a common scoring guide. A second path encourages unique and different learning tasks followed by a common demonstration task and a common scoring guide. The final pathway encourages unique learning experiences and unique demonstration tasks again followed by a common scoring guide. Each of these pathways can produce valid, reliable, and comparable results while enabling increased personalization for each student.

Innovative Schools. NESSC sponsors a League of Innovative Schools, involving more than 70 schools from the five states that participate in a professional learning community for schools. School leaders participate in site visits, online dialogues, and a great conference.

Where do graduates from these proficiency-based schools go to college? NESSC asked colleges and universities in member states to sign a pledge endorsing proficiency-based practices and assuring that no applicant is disadvantaged by coming from a school that uses standards-based reporting and transcripts. To date, 48 colleges and universities have signed the pledge, and that number continues to grow.

Proficiency tools. NESSC has a great Glossary of Educational Reform that “attempts to present terms and ideas neutrally, even presenting differing opinions of various concepts,” according to Ruff. A set of Leadership Briefs dive into a little more detail–just right for school board members.

It’s important to note the productive triangle of NESSC, New Hampshire’s great competency education policy environment, and support from Nellie Mae Education Foundation (Donohue was commissioner in New Hampshire when this all started). In addition, each of the NESSC states has made significant progress in state policy supporting this effort. A new statute in Maine requires demonstrated proficiency for graduation beginning in 2018. The Vermont State Board of Education has developed and is scheduled to approve in December a new graduation policy that will require proficiency-based graduation. Rhode Island has redesigned their Basic Education Program which pushed proficiency-based graduation including senior exhibitions for graduation. And in the last legislative session this past spring, Connecticut redefined “credit” to include student demonstration of knowledge. Great policy work has taken place in these states; these states are now working to spread the work in a handful of schools ubiquitously across all schools.

The shift from marking time to show what you know is on. NESSC demonstrates that a regional school network can make a big difference with a combination of leadership and support.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.